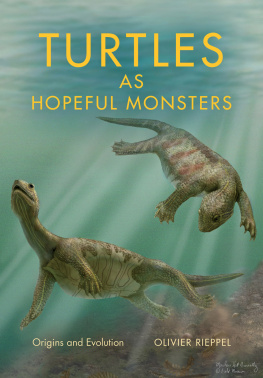

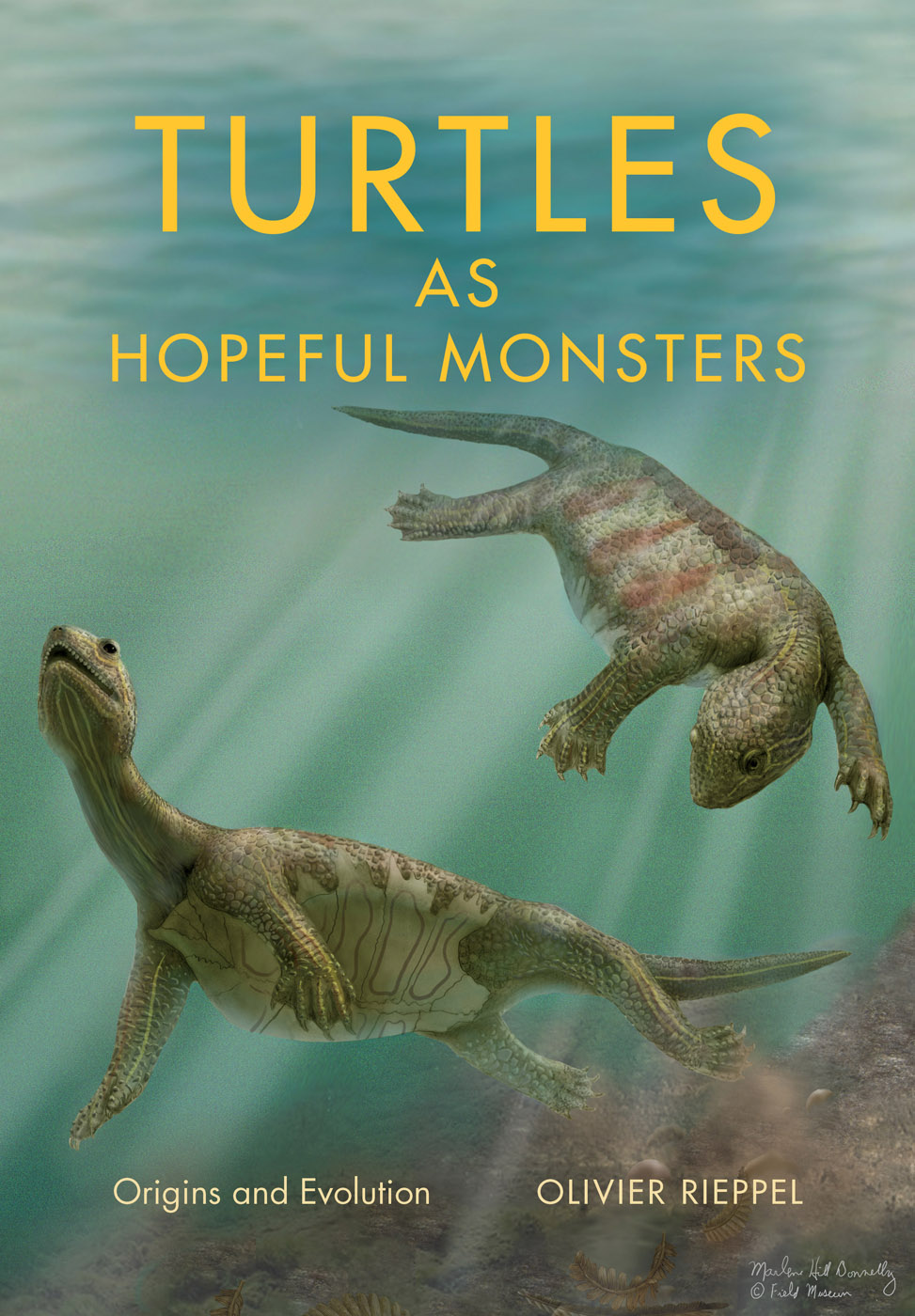

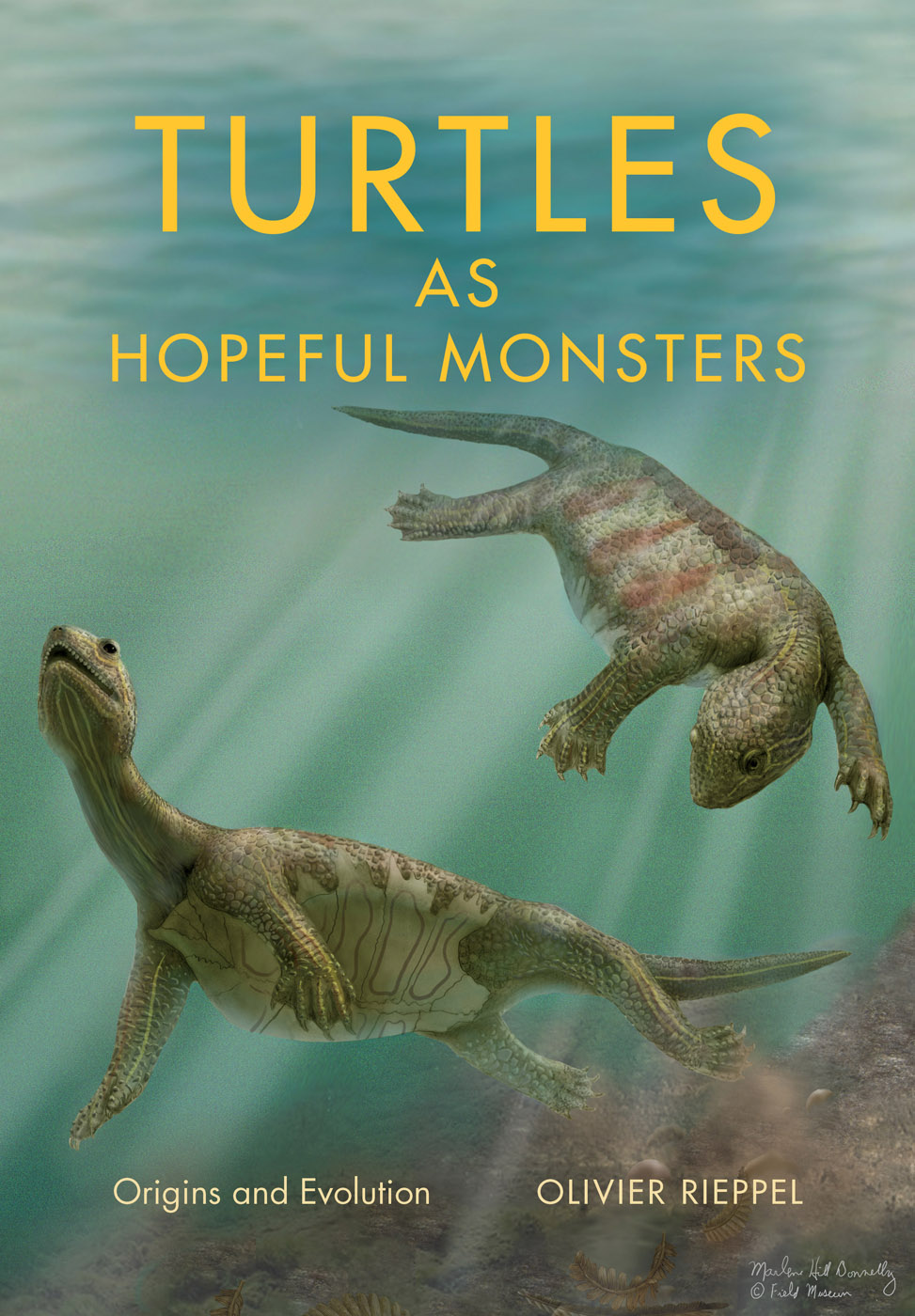

Turtles as Hopeful Monsters

Life of the Past

James O. Farlow, editor

Indiana University Press | Bloomington and Indianapolis |

TURTLES

AS

HOPEFUL MONSTERS

Origins and Evolution | OLIVIER RIEPPEL |

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by Olivier Rieppel

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rieppel, Olivier.

Title: Turtles as hopeful monsters / Olivier Rieppel.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, [2017] | Series: Life of the past | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031981 (print) | LCCN 2016050733 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253024756 (cl) | ISBN 9780253025074 (eb)

Subjects: LCSH: Turtles. | Turtles Evolution. | ReptilesEvolution. | Evolutionary paleobiology.

Classification: LCC QL666.C5 R57 2017 (print) | LCC QL666.C5 (ebook) | DDC 597.92dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031981

1 2 3 4 522 21 20 19 18 17

Contents

C

Acknowledgments

A

I AM VERY GRATEFUL TO LI CHUN, INSTITUTE OF VERTEBRATE PALEontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing, who invited me to collaborate in the description of many fine fossils he collected. I am equally thankful to Janice Frisch, acquisition editor at the Indiana University Press, and series editor James O. Farlow for their interest in the project, as well as their help and support to see this book through to publication. Marlene Donnelly (scientific illustrator) and John Weinstein (photographer) from the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, offered their help and expertise in the illustration of the book. Christine Giannoni offered equally invaluable help in obtaining often obscure literature.

The Henry Fairfield Osborn Papers, curated in Archives of the American Museum of Natural History, were kindly made available by my son, Lukas Rieppel. I also thank the staff at the German Federal Archives (formerly Berlin Documentation Center) and the University Archives of Gttingen and Greifswald for their help and support in my research.

Last but not least, I thank my wife, Myriam, and our sons, Michael and Lukas, who accompanied me on a journey that allowed me to pursue the research recounted in this book.

Turtles as Hopeful Monsters

Introduction: Turtles as Hopeful Monsters

I

HERE THEY ARE, STILL WITH US, BOXED UP IN A SHELL, SEEMING survivors of the distant geologic past: prehistoric creatures that both predated and outlived the dinosaurs. As a symbol in Hindu and Chinese mythology, the turtle supports the earthbut what supports the turtle? The philosophically intriguing answer is this: its turtles all the way down. Sluggish on land, seemingly stubborn in their behavior, turtles came to symbolize longevity, strength, and endurance in ancient China. The longevity of the turtle lineage is indeed remarkable, as is its evolutionary strength if measured by the numbers of species that have populated Earth for at least 220 million years, which is the approximate age of the oldest fossil turtle currently known. (For a discussion of fossils some 260 million years old, controversially interpreted as the oldest stem-turtle, see .) In spite of their highly constrained body plan, turtles show a surprising potential for evolutionary diversification, with species that conquered a great variety of habitats: forests and grasslands, deserts and karst mountains, rivers, ponds, lakes, even the open sea, with some 331 living species currently recognized (Fritz and Havas, 2007; van Dijk et al., 2012).

As Adler has remarked, Turtles are one of natures most immediately recognizable life forms (2007:139), bizarre in their own way, which is what seems to attract peoples attention as well as scientists curiosity. Where do turtles come from, and how did their unique anatomy and bodily functions evolve? These are questions that have spurred intense research as well as heated debate for 200 years and more. Yet even in the wake of the development of revolutionizing techniques in modern molecular biology, the answer remains as elusive as ever. Progress has been made, but a lot still remains to be discovered.

The eminent twentieth-century evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky once noted, Nothing makes sense in biology except in the light of evolution (1973:125). Philosophers of biology Kim Sterelny and Paul E. Griffiths paraphrased this famous line as, Nothing in biology makes sense except in the context of its place in phylogeny, its context in the great tree of life (1999:379). To ask where turtles come from is to raise the question of turtle ancestry. It certainly is uncontroversial that turtles are reptiles, but that does not tell us what group of reptiles gave rise to the turtle lineage in the distant part. What was the ancestor of turtles? That question was certainly a legitimate one to ask in the middle of the twentieth century and earlier, when the study of fossils was largely motivated by the search for ancestors of still-living descendants. The study of fossils retrieved from successive layers of rock was at that time compared to leafing through an illustrated book on evolution, supposedly revealing a gallery of ancestors and descendants.

Paleontologists started to research the ancestry of turtles well back in the nineteenth century, but until recently, all the fossil turtles pulled from sedimentary rock spanning vast geologic time were already finished exemplars, complete with carapace and plastron. Its indeed turtles all the way down! In the 1970s and 1980s, however, the study of evolutionary relationships was revolutionized; comparative biology went through a cladistic revolution. The search for ancestors was rejected as dilettante science; instead, the search for sister groups became all the rage. When, through evolutionary time, a species lineage splits into two, the stem species gives rise to two daughter species. These two daughter species are sister species; their respective descendants thus form sister groups. Rather than asking what was the ancestor of turtles, the questionin the aftermath of the cladistic revolutionmust be, what kind of a reptile species was it that shared with the turtle lineage a common ancestor that was not also ancestral to any other reptile lineage? In other words, which lineage of reptiles is more closely related to turtles than either is to any other reptile group? To answer this question requires some foundational knowledge about the basic structure of the reptile skull and the various modifications it underwent as reptiles diversified into turtles, crocodiles, lizards, and snakes. This is because the skull, as well as other parts of the skeleton, may hold the key to understanding turtle origins. More recently, molecular data, in particular DNA data, have in large measure been adduced in the search for turtle origins. But in spite of all these efforts, the deep evolutionary history of the turtle lineage remains only dimly lit.

Next page