Jeffrey E. Lovich

and Whit Gibbons

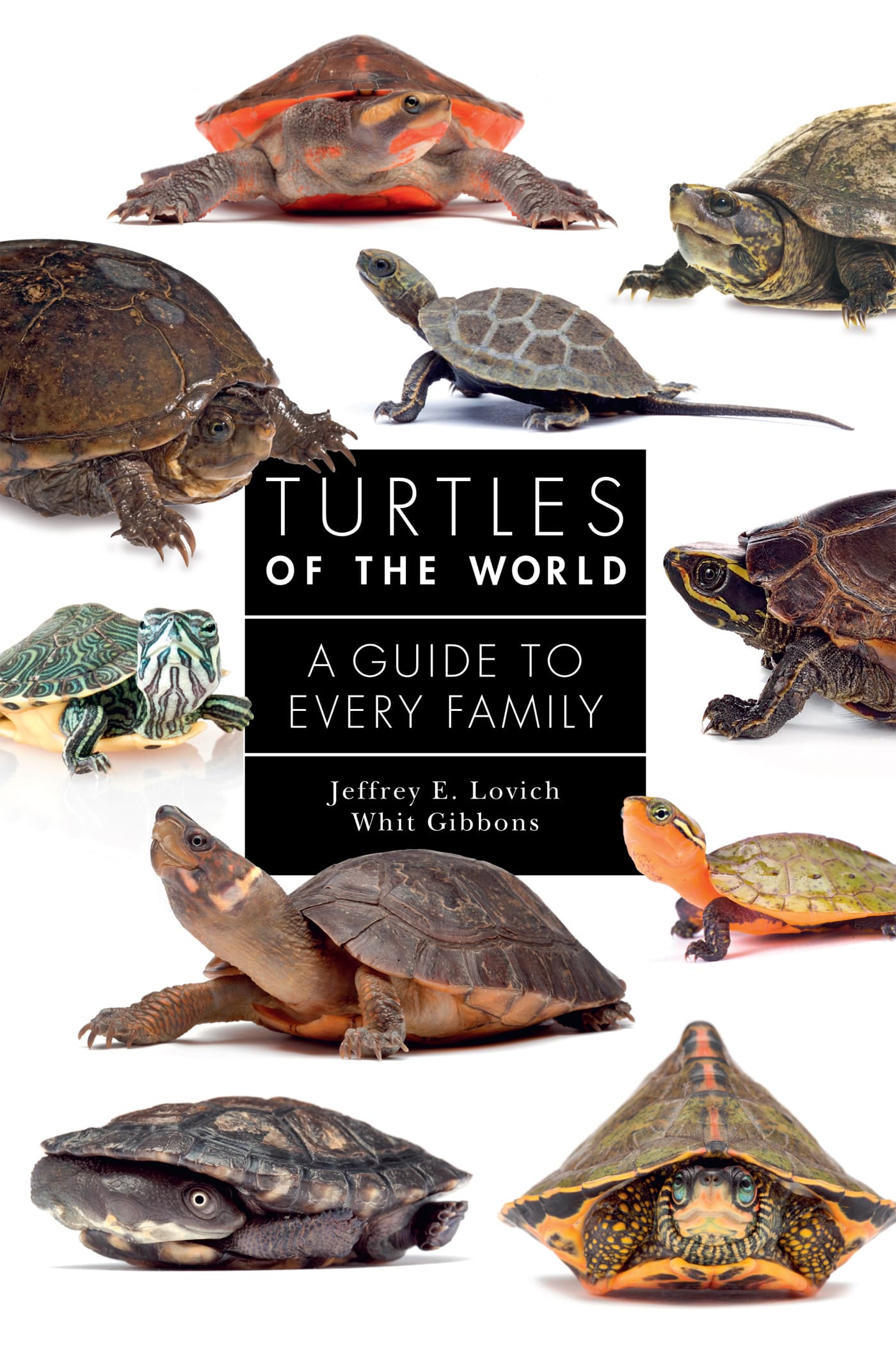

Turtles are arguably the most successful vertebrates to have ever lived. These iconic animals have been symbolized, memorialized, utilized, and revered by cultures throughout the world for thousands of years. They have changed little in appearance over 200+ million years due to the origin and retention of a morphology and lifestyle unique among vertebrates but which has endured the test of time. Instantly recognizable by their trademark bony shell, turtles are the only vertebrates, living or extinct, to have their limb girdles (hips and shoulders) inside the shell formed by their rib cage. On the one hand, the turtle shell appears to be an ingenious form of protective armor against many predators and the elements, while on the other the shell would appear to be a liability from the standpoint of mobility and other life functions.

Turtles have a variety of traits humans consider to be of interest. The sex of hatchlings is often determined by incubation temperatures of eggs in the nest, not genetically by X or Y sex chromosomes. Some female turtles have the ability to store viable sperm for several years after one mating, and embryos can have multiple sires in the same clutch. In northern latitudes, turtles basically hold their breath for several months during hibernation under ice. Some species have the ability to breathe through their cloaca as if it were a gill. The longevity of some turtles is widely recognized. Turtles are truly amazing animals!

The beautiful Diamond-backed Terrapins of North America live only in brackish water habitats and are the only members of their subfamily with spots instead of stripes.

Interest in turtles is growing rapidly as measured by popular and scientific publications (Lovich and Ennen 2013). Unfortunately, this rise in curiosity is paralleled by dramatic declines in turtle populations and extinctions of turtle species around the world. Turtles are unquestionably under siege on local, regional, and global scales, with a growing number of species threatened with extinction. More than half of the worlds turtles require some form of conservation action to protect them the proportion of turtles in trouble eclipses virtually all other major vertebrate groups except primates. They survived the extinction of dinosaurs, drifting continents, and numerous ice ages punctuated by rising sea levels. Whether they will survive humans remains to be seen.

A major purpose of this book is to increase appreciation for these successful creatures, largely unchanged since the mists of time, and expand awareness of their plight in the modern world. We provide a broad overview of general biology, fossil history, and distribution patterns of turtles. We also give details of the ecology and behavior of each of the 14 living families and 95 genera, highlighting some of the remarkable adaptations of selected species. Despite their antiquity, biological knowledge of many turtle species remains incomplete, but we have gleaned material for this book from a large and growing scientific literature base. We provide a list of suggested references for anyone interested in pursuing further details of particular species.

WHAT IS A TURTLE?

TURTLES VS. TERRAPINS VS. TORTOISES

People call turtles by various names including tortoises and terrapins. Technically, all animals with a bony shell and a backbone are turtles, even tortoises and terrapins. Just like foxes are dogs and lions are cats, tortoises and terrapins are turtles. Tortoises are decidedly terrestrial turtles with club-like hind feet. The word terrapin is derived from a Native American word meaning turtle. Simply put, all tortoises and terrapins are turtles, but not all turtles are tortoises or terrapins.

Common names of turtles vary regionally and we have adhered mostly to those recommended in Turtles of the World Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status (8th edition; 2017). Scientific names of turtles are generally reliable for distinguishing between species but are in a state of flux because of phylogenetic reinterpretations and descriptions of new species. We use the classification system for families, genera, and species accepted internationally by the majority of turtle biologists at the time of writing, as specified in the checklist mentioned above. We have augmented the list by including several species undescribed at the time of that publication. Taxonomy is an everchanging field, with more changes forthcoming. Turtles have not changed for centuries, but what we call them continues to be a moving target.

CONTINENTAL SPECIES DIVERSITY OF TURTLES

North America

99 species

South America

58 species

Europe

8 species

Africa

59 species

Asia

95 species

Australasia

39 species

Species diversity of non-marine turtles found on six continents and their associated island systems, based on the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group, 2017. The exact numbers change every year as new species are described but general continental relationships remain comparable, with the highest diversities being in North America and Asia.

The Pig-nosed Turtle of Australia and New Guinea is the only species in its family and the only freshwater turtle with flippers.

TURTLE BIODIVERSITY

The greatest concentrations of turtle biodiversity in the world are in the southeastern USA and southern Asia. Buhlmann et al. (2009) listed the total number of non-marine species for the USA as 53, while Asia has 77 species. The Mediterranean region of Europe has 14 native species, Australia 35, Africa 48, and Central and South America 51 and 48 respectively but includes overlap of some species among these regions. Notable concentrations of non-marine turtle species also occur in the Galapagos Islands (13) and on Madagascar (nine). These estimates vary from more recent compilations, including ours (see map opposite), due to recognition of new species and taxonomic disagreements.

The number of kinds of turtles recognized by the scientific community has steadily increased for decades as new species have been discovered in previously understudied regions. For example, the number of new species described per year worldwide has been almost ten times greater in recent years than in the USA where turtle research and descriptions of new species have been in progress much longer (Gibbons and Lovich 2019). Species diversity in Australia is also now better understood and unlikely to change much compared to Asia or Africa where extensive research programs are becoming established.