DEDICATION

To the Kihansi Spray Toad Nectophrynoides asperginis a small victim of development. May we learn to value all wildlife.

Published by Struik Nature

(an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd)

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

The Estuaries No. 4, Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue Century City, 7441

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000 South Africa

www.randomstruik.co.za

First edition published in 2005

This edition published in 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright in text, 2014: Bill Branch

Copyright in photographs, 2014: Bill Branch (unless otherwise indicated alongside image)

Copyright in maps, 2014: Bill Branch

Copyright in published edition, 2014: Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Publishing manager: Pippa Parker

Managing editor: Helen de Villiers

Editor: Emily Bowles

Designer: Neil Bester

Reproduction by Hirt & Carter Cape (Pty) Ltd

Printed and bound by Replika Press Pvt Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner(s).

ISBN 978 1 77584 165 4

ePUB 978 1 77584 257 6

ePDF 978 1 77584 258 3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the following colleagues for letting me use their photographs: Kenny Babilon, Wolfgang Bhme, Marius Burger, Paul Freed, Chris Kelly, Warren Klein, Reto Kuster, Simon Loader, Johan Marais, Michele Menagon, Mark-Olivier Rdel, Steve Spawls, Colin Tilbury, Phillip Wagner and Wolfgang Wurster. Emily Bowles was an able editor, and maintained consistency, style and deadlines. Joe Beraducchi (BMT, Arusha), allowed his rare captives to be photographed. I thank Steve Spawls, whose whose knowledge of the biology and distribution of East African reptiles made this guide so much more accurate.

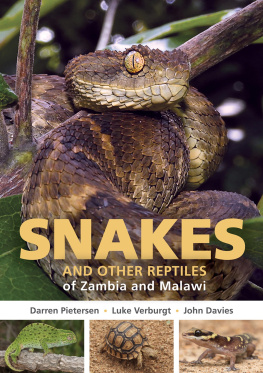

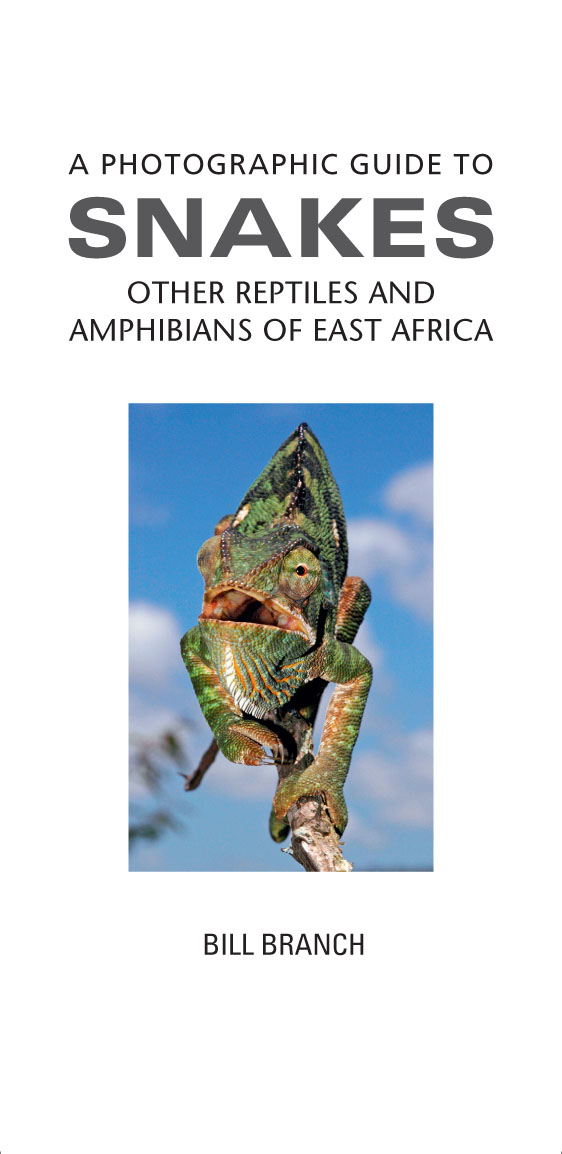

Front cover photograph: Rufous beaked snake Rhamphiophis rostratus

Back cover photograph: Yellow-spotted tree frog Leptopelis flavomaculatus

Title page photograph: Flap-necked chameleon Chamaeleo dilepis

CONTENTS

KEY TO SYMBOLS USED IN THIS BOOK

Snakes whose bite can be fatal to humans

Snakes whose bite can be fatal to humans

Venomous snakes whose bite is not known to be fatal

Venomous snakes whose bite is not known to be fatal

INTRODUCTION

This book introduces 274 of the snakes, lizards, crocodiles, chelonians and amphibians that live, often unnoticed, all around us. East Africa includes here the countries of Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania, and has a combined area of approximately 1,819,000km2 (about 20% of the size of the United States of America). It is host to a tremendous variety of habitats that harbour a magnificently diverse reptile and amphibian fauna. Over 450 reptile species have been recorded from East Africa, as well as more than 230 amphibians. Many of these are endemic, particularly to the isolated mountain regions, such as the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania, which are a global hot spot of biodiversity. Unfortunately, not all species can be included in this small guide, and those chosen emphasise the more colourful and conspicuous species, as well as those unique to, common or endangered in East Africa. It is to be hoped that this small book will help to enrich wildlife experience and will convince readers that this wonderful thing called life must be preserved in all its fabulous diversity.

Living reptiles are extremely diverse and the relationships between the main orders and families are still controversial. Three of the four surviving lineages occur in East Africa, including the crocodilians (Order Crocodylia); tortoises, terrapins and turtles (collectively called chelonians, Order Testudines); and the scaled reptiles include snakes and lizards (collectively called squamates, Order Squamata). Crocodiles are more closely related to dinosaurs and birds than to other reptiles, and chelonians have little similarity to other living reptiles. Among scaled reptiles, lizards are the ancestral group from which snakes and worm lizards (also called amphisbaenids) evolved. Limb loss in lizards has evolved many times, and it is not always easy to distinguish legless lizards from snakes. Most snakes have enlarged belly scales (ventrals) that aid locomotion, whereas legless lizards do not. In addition, the eyes of snakes lack eyelids and they have an unblinking stare. However, many snakes that burrow have evolved to be eyeless and without enlarged belly scales. Burrowing lizards may also become blind, and look very similar to burrowing snakes. There is no simple rule for telling them apart, but all blind snakes have very short tails with a sharp spine at the tip, and their heads are rounder and blunter than those of legless lizards.

Lizards, like this agama, are part of the ancestral group from which snakes and worm lizards descend.

Snakes may range over large areas as they search for prey. Lizards, however, often inhabit very specific places.

Reptiles have only limited mobility and many have very specific habitat requirements. In general, lizards can be considered habitat-linked, while snakes can be considered food-linked. This is reflected in many of their common names. Thus, among snakes, we talk of egg eaters, centipede eaters and slug eaters, and among lizards, of desert lizards, rock lizards and water monitors. In practical terms, this means that lizards often have very small ranges within which they inhabit specific places. Snakes often range over large areas and occur in different habitats, but search for specific prey.

The majority of reptiles, including all crocodiles and chelonians, are oviparous (egg-laying). Most lay clutches of between five and 20 eggs, although large sea turtles may lay up to 1,000 eggs in a season. By contrast, most geckos lay only two eggs at a time. With few exceptions, parental care in all local reptiles ends when the eggs are laid and the nest sites are covered. The exceptions are pythons and crocodiles, which both attend their eggs until they hatch. A few other snakes also stay with their eggs after laying them, although this is poorly studied. In crocodiles and many chelonians, the sex of the embryo is dependent upon the temperature at which the egg is incubated. In crocodiles, males develop in eggs at high temperatures, while the same temperatures in chelonians usually produce females. Many snakes and lizards are viviparous, retaining their eggs within the body and giving birth to live young. This is usually associated with life in cool climates.

Most African amphibians are anurans (Anura) that have well-developed legs and lack tails as adults. Tailed amphibians (Caudata: newts and salamanders) are absent in sub-Saharan Africa, although common in the northern hemisphere. The rare Gymnophiona (caecilians) are legless amphibians with rubbery bodies that live underground in damp soil. They occur in the tropical regions of South America, Asia and Africa, with few African (20) or East African (10) species. Amphibians are characterised by having a larval stage (the tadpole or pollywog) that is usually free-swimming. Some species, however, lay large yolky eggs in damp soil where the tadpole grows within the egg, emerging as a miniature froglet. In some frogs the eggs are even retained within the mother, who then gives birth to live young.

Next page

Snakes whose bite can be fatal to humans

Snakes whose bite can be fatal to humans Venomous snakes whose bite is not known to be fatal

Venomous snakes whose bite is not known to be fatal