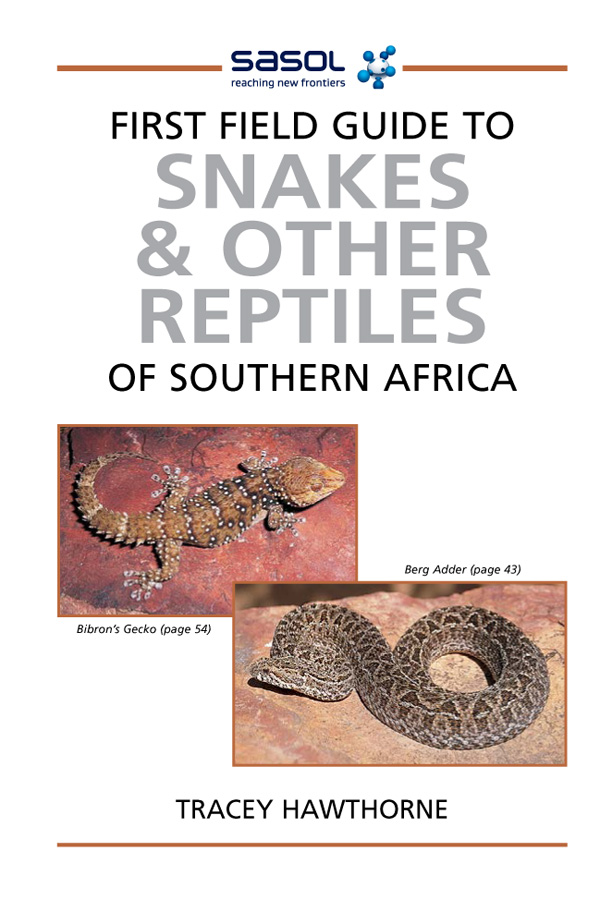

Contents

Herald or Red-lipped Snake

Rock or White-throated monitor

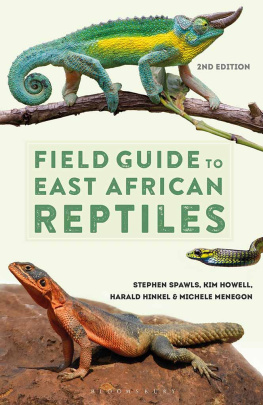

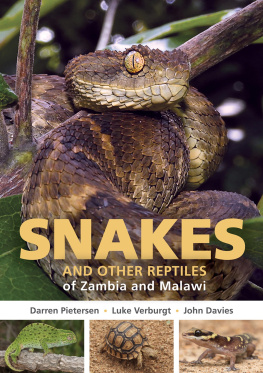

Southern African reptiles

Most people, when asked whether they like reptiles, will shudder and say either, Yuk! Theyre all cold and slimy! or No way! Theyre poisonous! In fact, the former is untrue and the latter applies to surprisingly few species in our region (see A note on venoms, ).

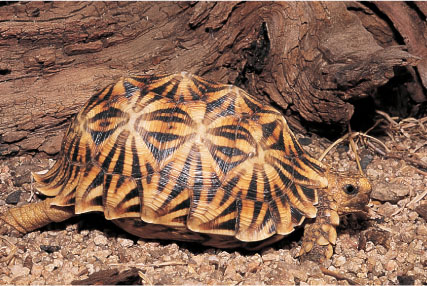

All reptiles have a dry, horny skin, usually modified into scales or plates. And, although they are cold-blooded, their blood may actually be just as warm as any other living creatures: the term cold-blooded refers to the fact that all reptiles obtain their heat from external sources (usually the sun, which is why so many reptiles enjoy basking), unlike mammals and birds, which generate heat internally. Warm-blooded creatures (like humans) need a constant supply of food to continually generate heat; some reptiles, on the other hand, can survive on as few as 10 meals a year.

Reptile ancestors were the early amphibians that crawled out of the seas about 370 million years ago; a group of these evolved into reptiles.

Flap-necked Chameleon

In southern Africa, we have 480 species of reptiles, including the worlds richest diversity of land tortoises. More than half are endemic. Although only 46 of the most common reptiles have been included in this book, it is hoped that this selection will illustrate how interesting, resourceful and hardy and, in many cases, beautiful the reptilian life of southern Africa is, and encourage further investigation of this fascinating world.

Habitats

Regions

How to use this book

Each species account is split up into several headings. These are explained below.

Common name: The common name is the English name by which the reptile is known.

Scientific name: This is the official name by which it is known worldwide and is always written in italic type, e.g. the Nile Crocodile is known by its scientific name of Crocodylus niloticus.

African names: Where available, the reptiles name is given in Afrikaans (A), Xhosa (X) and Zulu (Z), which, along with English, are the most commonly spoken languages in South Africa.

Length: Snakes, lizards, geckos, chameleons and crocodiles are all measured in a straight line along the backbone, from the tip of the snout to the tip of the tail. Only the shells of turtles, tortoises and terrapins are measured, along the midline of the carapaceG. Use the ruler on the outside back cover to give you a realistic idea of the size of the reptile.

Identification: Characteristic physical features, colours and patterns (the parts of the different reptiles are illustrated on ).

Where found: The immediate environment preferred by the reptile (near water, for instance, or under loose leaf litter). The habitat map (on ) shows the South African provinces. These maps, used in conjunction with the distribution map that accompanies each species account, will tell you where the reptile occurs. The southern African region includes South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

Spotted Bush Snake

Habits: Different reptile have different social and feeding habits, and those with which you may not be familiar are marked with a G. A definition of these words is given on , in the Glossary.

Reproduction: Short notes on eggs or live young, as well as incubation periods.

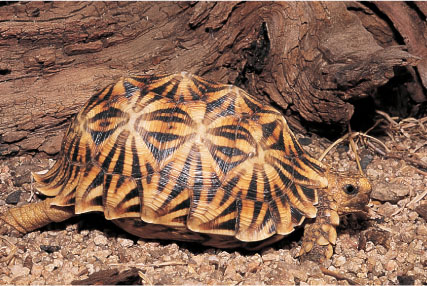

Serrated or Kalahari Tent Tortoise

Notes: Anything of special significance or interest.

Status: Whether the reptile is endemicG, and protected, common or widespread. Not all species have been assessed for the IUCN Red ListG.

Venom: Notes on type of venom, where relevant.

Food: What the reptile eats.

Similar species: Bear in mind that in many cases similar-looking species do not necessarily occur in the same location or habitat as the reptiles discussed in this book.

More about reptiles

Indentifying reptiles

When identifying a reptile for the first time:

- Take careful note of its general shape. Does it have legs or a long, smooth tail? Is the body fat and covered with spines? Note whether the head, body and tail differ in colour and pattern.

- Look through this guide to find a photograph most closely resembling the specimen you have spotted, and check the distribution map to see if it has been recorded in your area.

- Note the habitat in which it is living. Are you in a semi-desert region? Near a water hole or river? Is the animal sheltering under a rock or hiding in a tree? Compare this with the notes under Where found.

- Observe the behaviour of the animal. Did it run up a tree or into a hole in the ground? Check against the notes under Habits.

A note on venoms

Snakebites do occur, albeit rarely, and serious bites require treatment with antivenom. Cutting and sucking around the bite or applying a tourniquet will not work and, in fact, may cause further damage. The most important thing to do is to keep the victim calm and still, and get him or her to the nearest medical facility as soon as possible. If you can do so safely, photograph the snake so it can be positively identified.

A note on reproduction

Most reptiles are oviparous (lay eggs), but some are viviparous (give birth to live young).

Where to see reptiles

It takes patience to find reptiles: most are shy and scurry to safety at the first hint of danger. Look under boulders, rotting logs and grass piles; rubbish dumps are prime reptile habitats. Burrowing reptiles can be found by digging in loose soil under boulders and rotting logs. Check holes in the ground and stormwater drains that may act as pitfall traps. In cooler regions, hibernating snakes and lizards can be found in old termite nests, and rock-living specimens in deep rock crevices.

When to see reptiles

Night searches often yield success: NocturnalG reptiles sometimes crawl onto still-warm roads at night, geckos collect around night lights where they feed on insects, and chameleons stand out against dark foliage in torchlight. Early in the morning, before wind and the passing parade obliterate evidence, reptile trails can be followed in loose sand, particularly in spring, when males are actively looking for mates.

Next page