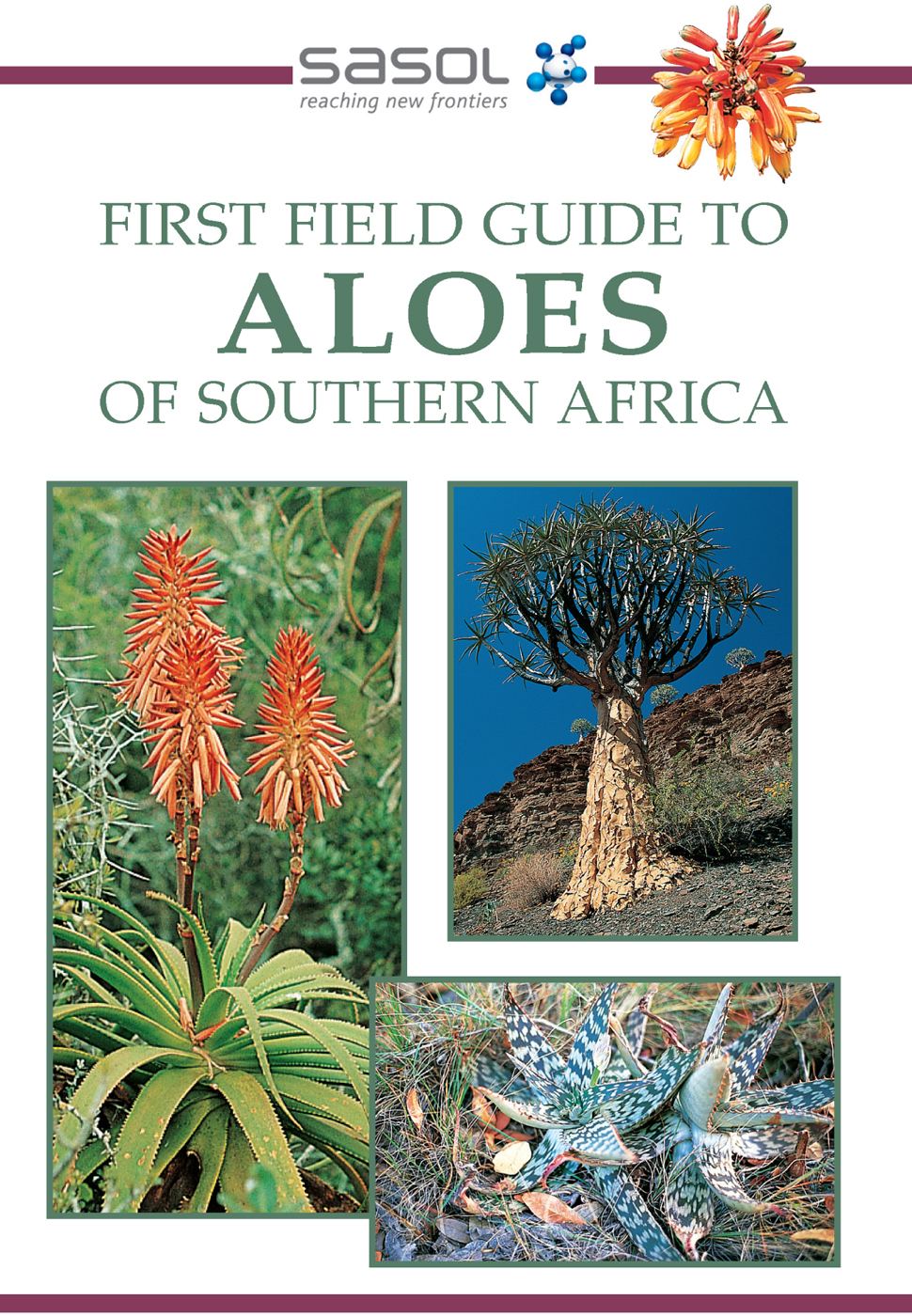

FIRST FIELD GUIDE TO

ALOES

OF SOUTHERN AFRICA

GIDEON SMITH

Contents

Aloe excelsa (page 26)

Published by Struik Nature

(an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd)

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Road,

Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000

South Africa

Visit us at www.randomstruik.co.za

This ebook edition pulished in 2011

First published in print in 2003

Copyright in text, 2003, 2011: Gideon Smith

Copyright in photographs, 2003, 2011: individual photographers as credited on page 56, 2003

Copyright in maps, 2003, 2011: Gideon Smith

Copyright in published edition, 2003, 2011: Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Editor: Katharina von Gerhardt

Designer: Lesley Mitchell

ISBN: 978 1 86872 854 1 (Print)

ISBN: 978 1 43170 249 7 (Epub)

ISBN: 978 1 43170 250 3 (PDF)

Introduction

Aloes come in an astonishing array of different shapes and sizes. They range from the lofty tree aloes, such as Aloe barberae and Aloe dichotoma, which may reach a height of 20 m, to the tiny white grass aloe, Aloe albida, and the miniature Aloe bowiea - both barely 100 mm tall. Between these extremes, almost every conceivable combination can be found: single-stemmed trees, dainty or robust shrubs, ground-hugging creepers, and even a few cliff-dwellers that grow vertically downwards. They also vary tremendously in the size, shape and arrangement of their leaves, ranging from massive, broad and boat-shaped to tiny, narrow and grass-like, and from rigidly upright to droopy and dangling. The margins and surfaces of the leaves of some aloes are virtually without teeth, while others have sharp spines along the horny edges, or teeth that may be scattered on the upper and lower surfaces. Not to be outdone, the flowers also differ considerably in shape, arrangement and colour. Those of some species are dainty, bell-shaped and off-white, while others have robust, bright red tubes exuding copious amounts of nectar. The endless combinations in which these characters are expressed serve to make aloes irresistible to collectors, gardeners and horticulturistsG.

More than 500 species of Aloe are known in the world - 120 of these species are indigenousG to South Africa.

Aloe petricola will brighten up any garden in winter.

Characteristics of Aloe species

Aloes are generally included in the subfamily Alooideae of the family Asphodelaceae. An alternative point of view is that they, along with their relatives in the look-alike genera Astroloba (star-lobes), Chortolirion (kleinaalwyn), Gasteria (beestong), and Haworthia (kleinaalwyn or rosies), should be treated as belonging to their own family, the Aloaceae. Regardless of which family classification is followed, certain features characterise aloes.

Not an aloe! Century plants look superficially similar to aloes, but they die after having flowered. Plants in this colony of Agave vivipara var. vivipara are in various growth phases. Some have flowered and are now dying back.

The most obvious are:

Fleshy leaves, even if only very slightly, arranged in dense or sparsely leaved rosettesG.

Clusters of tubular flowers arranged on elongated or compacted, often candle-like, inflorescencesG.

Certain unrelated succulent plant species look very much like aloes as they too have their spine-edged, boat-shaped leaves arranged in rosettesG. One group in particular, representatives of Agave, the Century plants, look very much like aloes, but they are mostly found in the subtropics and deserts of central America, Mexico and the southwestern United States of America. Furthermore, they die after having flowered, while aloes are long-lived and flower repeatedly. One species, the Mexican Agave americana (blougaringboom), which is widely grown in South Africa, especially in the arid, karroid areas, is used for the production of a high-quality, tequila-like alcoholic beverage.

Growing aloes

Part of the popularity of aloes among collectors and gardeners can be attributed to the ease with which they can be grown. Aloes are propagated primarily through cuttings and seed. Of these two methods, the establishment of new plants through taking cuttings and planting them is by far the most popular. Shrubby and tree-like species, in particular, are propagated in this way. All that needs to be done is to remove a side-branch or basal sprout with a sharp knife and allow the wound to dry off for a few days, after which it can be planted in a well-drained friable soil mixture in a container, or directly in the ground. The cut end can be dipped into commercially available root hormone powder to enhance the formation of roots.

Alternatively, aloes can be grown from seed. This method is very rewarding, as, with the exception of a very few species, aloes are particularly easy to grow from freshly harvested seed. Seed should be spread evenly on the surface of a well-drained soil mixture containing about one part coarse river sand, one part sifted compost and one part loamy garden soil. Cover seed with a thin layer of small pebbles and water thoroughly from the bottom by standing the seedling tray in a shallow container filled with water, so as not to disturb the seeds. If the soil is kept moist, tiny seedlings should emerge within a matter of days. After germination, the seedlings will benefit from a drenching with water to which a fungicide should be added. This will control fungal attacks, which often occur in aloe seedlings. Once their root systems are strong enough, usually within a few months, the seedlings can be transplanted into larger containers or garden beds. A modern trend in domestic and even corporate gardening practices is to use a large variety of plants that are low maintenance, yield a high return in terms of flower colour, attract wildlife to the garden, are hardy (i.e. water-wise) and highly architectural. Aloes satisfy all these requirements. In addition, they combine well with a variety of exotic species popular in gardening. When combined with other South African species, such as strelitzia, agapanthus, clivia, plumbago, pelargoniums and asparagus, aloes are shown to best effect.

Pests and diseases

As is the case with all southern African plants, indigenousG pests and parasites affect aloe plants. Fortunately it is comparatively easy to control most of the insect infestations that are normally found on aloes. Arguably the most severe and destructive aloe pest is the aloe snout beetle that burrows into the crown of the rosetteG where it lays its eggs. Once these hatch, the grubs burrow into the stems, which slowly deteriorate until the plant finally collapses into a heap. Small holes can be drilled into the stems of large plants and neat systematic insecticide can be injected into these as a