REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS

THE BRITANNICA GUIDE TO PREDATORS AND PREY

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS

EDITED BY JOHN P. RAFFERTY, ASSOCIATE EDITOR, EARTH AND LIFE SCIENCES

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

John P. Rafferty: Associate Editor, Earth and Life Sciences

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by David Nagle

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reptiles and amphibians / edited by John P. Rafferty.

p. cm.(Britannica guide to predators and prey)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-410-3 (eBook)

1. Reptiles. 2. Amphibians. I. Rafferty, John P.

QL641.R464 2011

597.9dc22

2010028543

On the cover and silhouetted pp. : A rattlesnake bares its fangs, which are capable of injecting deadly venom into its prey. www.istockphoto.com/Cory Thoemke

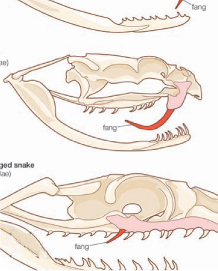

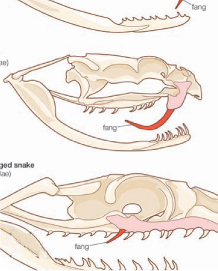

On page : Snakes (suborder Serpentes). Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.

On page : A giant tortoise of the Galapagos Islands. Rodrigo Buendia/AFP/Getty Images.

On pages : Banner. Siede Preis/Photodisc/Getty Images

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

P erhaps it is due to the fact that, according to some scientists, humans and reptiles shared a common ancestor over 300 million years ago, or, conversely, that reptiles appear to be completely dissimilar to human beings. No matter the core reason, these ubiquitous creaturesthere are more than 8,700 reptilian species on Earthhave aroused strong feelings of fascination in humans for thousands of years. Who could help but be intrigued by dinosaurs, thunder lizards crashing through primeval jungles or cruising through primordial seas?

Alas, dinosaurs are but one example of a group of reptiles that are now extinct. Other extinct lines include the mosasaurs, plesiasaurs, and ichthyosaurs. The reptiles that now exist, and are examined thoroughlyin broad strokes and by particular speciesin this book, are snakes, lizards, turtles, and tuataras. The worlds amphibians, noted and even named for their ability to lead a double life on land and water, are carefully explored in much the same fashion in this volume.

What makes a reptile a reptile? In general, all reptiles are air-breathing vertebrates. They have scales and reproduce through internal fertilization. Embryonic development involves a fluid-filled sac called the amnion. Singly, these features could be applied to other vertebrate groups, including mammals. However, taken together, only their close relatives the birds share these characteristics. Birds, however, are warm-blooded, or endothermic; the temperature of the body is maintained internally. All modern reptiles are cold-blooded, or ectothermic; the temperature of the body is largely dependent on the external environment. (Some extinct groups of reptiles, such as the ichthyosaurs and certain dinosaur lineages, are thought to have been warm-blooded.)

Nevertheless, from the smallest (skinks and geckos) to the largest (pythons and crocodiles), all reptiles depend upon heat from their surroundings for functional life processes, including locomotion. This helps account for the fact that the vast majority of reptiles are located in warmer climates, between 30 N and 30 S latitude. The highest diversity and number of reptiles have habitats in tropical and subtropical areas. Survival in changing environments can prove difficult for ectothermic creatures, so reptiles have adopted a number of behaviours that best help them cope. They tend to seek out habitats where there is minimal competition for land or mates. Many put on displays of ferocity rather than actually fight for territory or breeding partners.

More than half of all reptile species are classified in the order Squamata, a group that includes lizards and snakes. The defining characteristics of lizardsthe possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external auditory openingsare flexible in that many different types of lizards may not have one or more of these attributes. While most reptiles lay leathery fertilized eggs or bear live young, certain types of lizards can, under limited conditions, reproduce by parthenogenesisthat is, produce offspring from eggs that have not been fertilized.

Next page