Further Reading

Alcock, John. Sonoran Desert Spring. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Sonoran Desert Summer. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990.

Alexander, Kathy. Paradise Found. Mt. Lemmon, Az.: Skunkworks Productions, 1991.

Bowden, Charles. Frog Mountain Blues. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1987.

Gregonis, Linda M., and Karl J. Reinhard. Hohokam Indians of the Tucson Basin. Tucson:University of Arizona Press, 1979.

Harte, John Bret. Tucson: Portrait of a Desert Pueblo. Woodland Hills, Ca.: WindsorPublications, 1980.

Krutch, Joseph Wood. The Desert Year. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1985.

The Voice of the Desert: A Naturalist's Interpretation. New York: William Morrowand Co., 1971.

Larson, Peggy. The Deserts of the Southwest. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1977.

MacMahon, James A. Deserts. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1985.

Nabhan, Gary Paul. Saguaro. Tucson: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, 1986.

Olin, George. House in the Sun. Tucson: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association,1977.

Polzer, Charles W. et al. Tucson: A Short History. Tucson: Southwest Mission ResearchCenter, 1986.

Sonnischen, C. L. Tucson: The Life and Times of an American City. Norman: Universityof Oklahoma Press, 1987.

A Changing Canyon

Tuesday, May 3, 1887. Tucsonans are going about their business on a pleasantly warmafternoon under a cloudless sky

One hundred and fifty miles to the southeast, in northern Mexico, the ground suddenlylurches, heaving up a scarp over thirty miles long and up to twelve feet high. Apowerful ripple in the earth races out in all directions. It rumbles through Tucsonless than a minute later, stopping clocks at 2:12, swaying buildings, flinging crockeryto floors, shaking plaster from walls. Terrified citizens run out into the streetsand are sickened as the ground rolls beneath their feet. Amid the confusion, somelook in amazement toward the Santa Catalina Mountains north of town. What they seeis reported in the next day's newspaper: "When the quake struck the old Santa CatalinaMountains, great slices of the mountain gave way, and went tumbling down into thecanyons, huge clouds of dust or smoke ascended into the blue sky, high above thecrest of the queenly mountain.... Great boulders, or little mountains, wrestedfrom their seats by the shock, came thundering down into the valley, bounding overrocks and cutting their way through the air" (The Arizona Daily Star; May 4, 1887).

If anyone had the dubious fortune to be in Sabino Canyon at that moment, his or herrecollection of events there has been lost to us. We can imagine a terrifying scene:great blocks of stone breaking loose from cliffs, tumbling end-over-end, crushingcacti, plunging into the creek. But perhaps only a few rocks fell that afternoonin Sabino Canyon. By now nature has healed any wounds left by this episode, and wemay never know for certain.

Changes in Sabino Canyon are seldom dramatic. A wildflower grows, blooms, goes toseed. A cottonwood, stressed by drought, drops a dying limb. A flood shifts a rocka few feet downstream. Over a human lifetime, the canyon may seem to change hardlyat all.

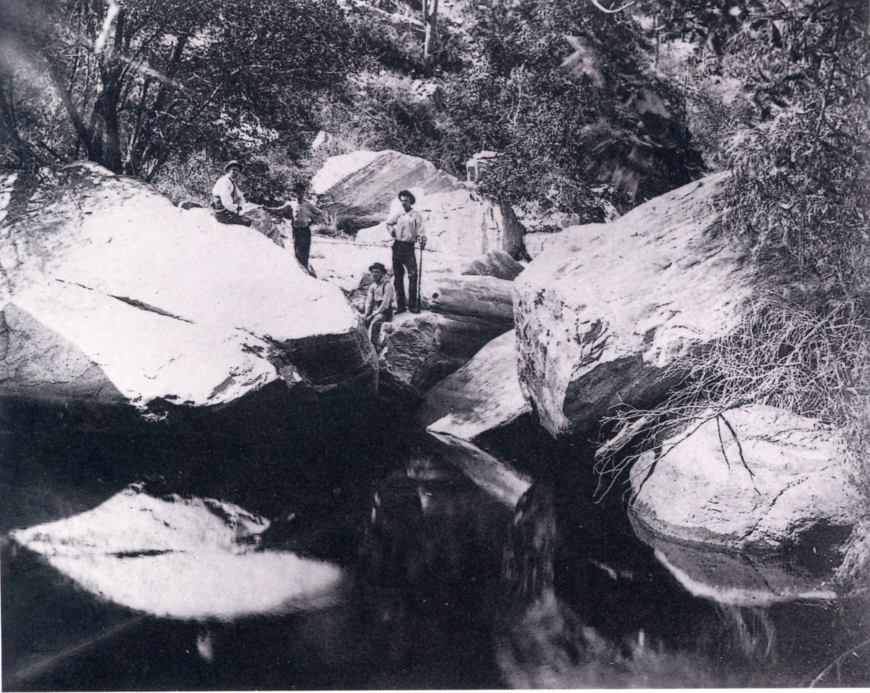

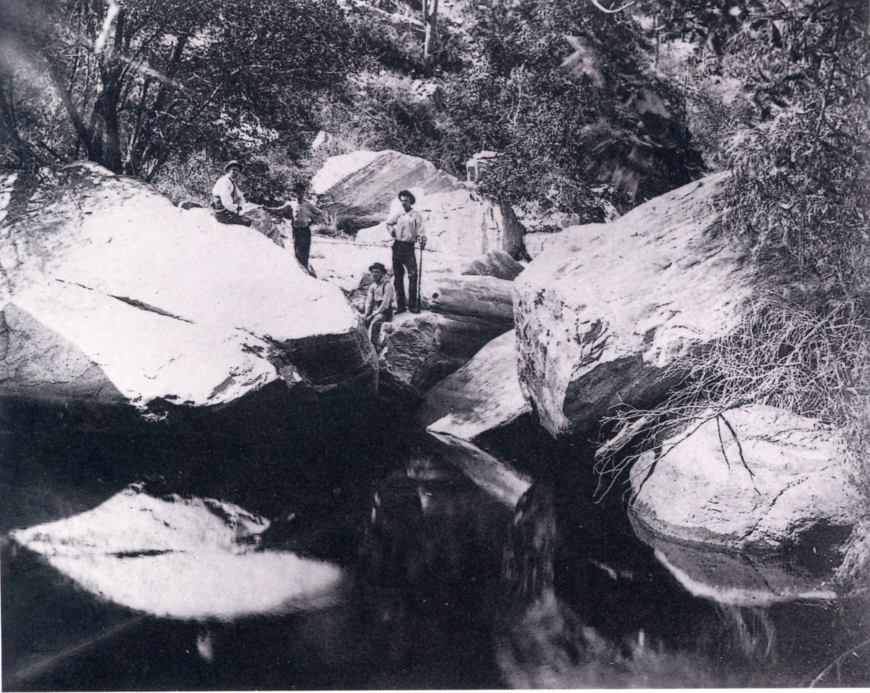

Photographs taken in Sabino Canyon a century ago show quaintly costumed men and womenin places we easily recognize. They are posing on the same boulders on which peoplesunbathe today. Only the plants in the background have changed: A willow is gone,but another has taken its place a few yards away. Going back two centuries takesus beyond the age of the photograph or even of written descriptions of Sabino Canyon.Yet, as we shall see in a later chapter, there is reason to believe that the canyon'svegetation was subtly different even then. Twelve thousand years ago, at the endof the last Ice Age, the canyon looked very different indeed. Twelve million yearsago, there was no Sabino Canyon at all.

The Evolving Landscape

Twelve million years ago, a precursor of the Santa Catalina Mountains already existedas a range of hills, but the enormous forces that were to create today's rugged mountainswere just coming into play. The crust of the earth in much of western North Americawas being stretched, and it cracked into huge blocks edged by steep faults. Overmillions of years some of these blocks became mountains, not by uplift as one mightexpect, but by being left in place while other blocks foundered around them, formingvalleys. The result is an odd up-and-down landscape called the Basin and Range Province,which stretches from northern Mexico into Oregon and Idaho, and includes much ofwestern and southern Arizona.

One of the earliest known dated photographs taken in Sabino Canyon, June 10, 1890.The site is easy to recognize today. Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson:photo 24377.

AGES OF ROCK

The banded cliffs of Sabino Canyon have confounded generations of geologists. Thesebeautiful formations are composed of a hard metamorphic rock called the "Catalinagneiss." By the early twentieth century, when geologists on horseback first mappedthe Santa Catalina Mountains, studies around the world had shown that gneiss (pronounced"nice") is created when another rock, such as granite or sandstone, is transformedby intense heat and pressure. Supposing that the gneiss in Sabino Canyon had beenformed in this way, scientists began a decades-long disagreement about its age andoriginal form. Some proposed that the light and dark bands were relics of layersin ancient sediments. Others suggested that the bands were formed by the meltingand recrystallization of granite. There were other theories as well.

In the 1970s a few geologists threw out old assumptions and formulated a startlingnew theory for the origin of the Catalina gneiss. If they are right and the lastword on this enigmatic rock has yet to be written the process began nearly a billionand a half years ago. At that very ancient time, when only the most primitive formsof life inhabited the earth, a mass of molten rock cooled deep underground, forminga huge deposit of granite. Much later, only about 45 million years ago, after thedinosaurs had come and gone, another mass of molten rock invaded the still deeplyburied granite, penetrating it in great fingers and sheets. Where the Santa CatalinaMountains would later appear, the earth s crust softened and stretched, smearingand thinning the older and newer layers before they cooled and hardened.

The dark bands we see today are the remains of the ancient granite, and the lightbands are the younger rock that invaded it. In retrospect, it is not surprising thatit was so difficult to discover the age of the rock in Sabino Canyons cliffs. Ithas not one age, but two.

Catalina gneiss

As the ground sank all around the particular chunk of the earth s crust that wasbecoming the Santa Catalina Mountains, streams carrying rainwater and snowmelt begancutting slowly into its flanks. They bore silt, sand, and gravel into the surroundingbasins, gradually filling them with sediments thousands of feet deep. Movement onthe faults surrounding the Santa Catalinas mostly stopped about five million yearsago, but the processes of erosion are continuing today in Sabino Canyon and in theother canyons of this mountain range.