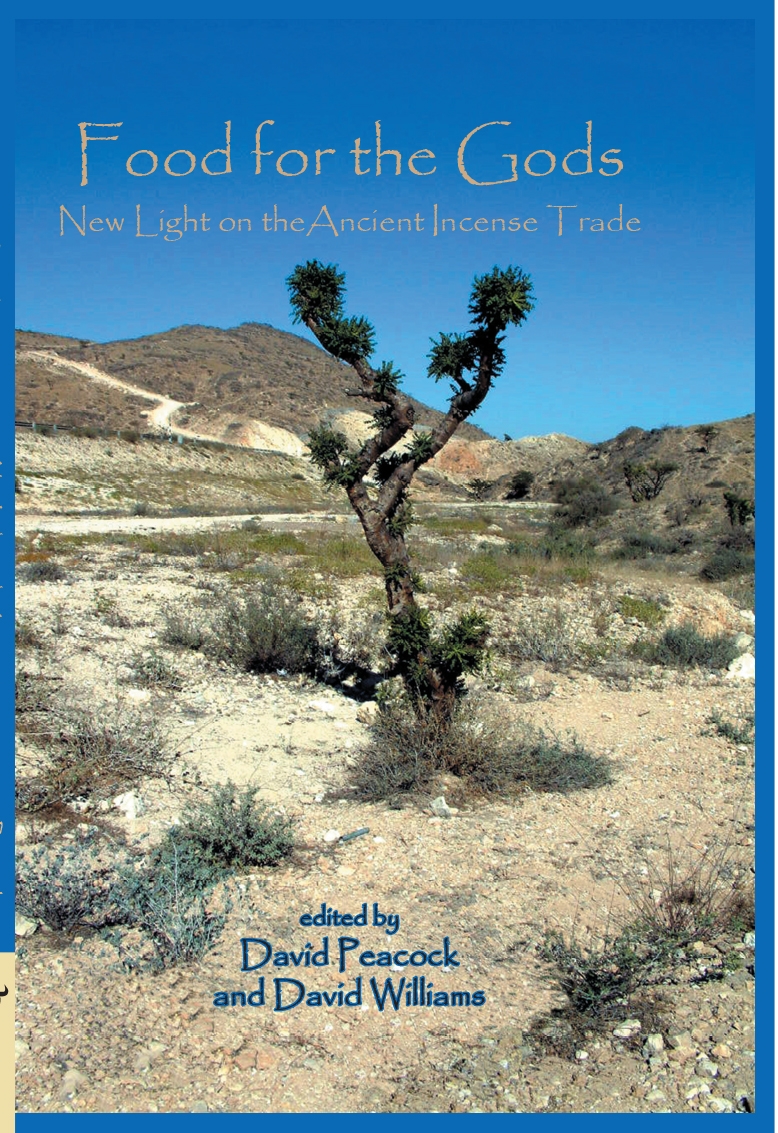

D. P. S. Peacock - Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade

Here you can read online D. P. S. Peacock - Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Rome (Empire), year: 2006, publisher: Oxbow Books, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxbow Books

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- City:Rome (Empire)

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

D. P. S. Peacock: author's other books

Who wrote Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

David Peacock and David Williams

The story of incense is one of the most intriguing in both eastern and western culture. From the first millennium BC to the present day it has been sought after and valued on a par with precious metals or gems. While there was undoubtedly symbolism in the choice of the three Sages gifts to the infant Christ, it is interesting to note that frankincense and myrrh, as well as gold, were thought worthy markers of this epoch making event. The history of the exploitation of the resins of Boswellia and Commiphora trees is outlined by Caroline Singer who relates how these unprepossessing plants produced a substance sought by emperors, priests, apothecaries and the common man alike. Throughout its long history it was a luxury associated with prestige and religion: the story is almost stranger than fiction. She gives a comprehensive account of the history of incense discussing the demand, the production and the growing areas as well as the means of distribution. As Myra Shackley shows, in the final chapter, its importance in religion persists to this day and it is used by perfumers, aromatherapists and in the production of medicines. Finally she assesses the potential for incense driven tourism. Its production is a significant element in the economy of the southern Arabian peninsular and modern frankincense routes bear an uncanny resemblance to the ancient.

Thus, while some of the papers in this volume attempt to paint a broad picture, emulating and updating Nigel Grooms seminal work Frankincense and Myrrh: A Study of the Arabian Incense Trade, our main, but not sole, focus is on the Roman period and the archaeology of incense. While the texts are informative they tell but part of the story and if the study is to progress we need the supplementary information that only archaeology can furnish. Here there is a problem because, unlike many luxury itemsfine pottery, metals or even textiles, it is seldom preserved in the archaeological record. A small fragment of frankincense, probably Islamic rather than Roman in date, was found in the recent excavations at Quseir al-Qadim, but it is in any case a single small fragment from an extensive excavation conducted over 5 years. Incense can be preserved in archaeological quantities, but it was so valuable that it was conserved and consumed rather than being discarded as rubbish. The chances of finding incense are considerably less than those of finding gold. Gold is a stable enduring material, incense requires suitable conditions of aridity or wetness to ensure its survival. If we are to study the use and distribution of incense this must usually be done indirectly, by looking for clues in more durable media. Fortunately, incense requires special apparatus for burning and the dissemination of aroma so that incense burners are without doubt a major means of getting to grips with the problem. Unfortunately, there have been few studies, partly because it is hard to be certain that an artefact would have been used for this purpose. The work of Hallet (1990) on Saudi Arabian steatite industries is a model for the Islamic period, and extraction may also have been practised in the Eastern desert of Egypt (Harrell and Brown 2000). Unfortunately, the use of steatite seems to be restricted to the Islamic period in the Near East and no Roman vessels have been found in this or any other lithic material. It seems that pottery vessels may have been used, or the incense burned in the specially made depression on the top of Roman altars. There must be organic material preserved in the pores of such loci and a programme of organic analysis might be helpful in both identifying the practice and the type of incense burned. However, in the absence of such work much can be done by purely archaeological methods. The chapter by Joanna Bird is an exemplary lesson on what can be achieved and we are privileged to republish this important work, with a few minor updates. Ceramic vessels with Mithraic motifs attest, forcefully, its role in Mithraic ceremonies.

Our chapter on ballast also illustrates a new approach to the problem of the incense trade. When we began our geochemical study we imagined that the picture would be a complex one with many different sources reflecting what we believed might have been cabotage along the coasts of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. We were astounded to find that the ballast dumps along the Egyptian coast were made up of material from but two sources: 70% Qana, 30% Aden. As Qana was above all the major port for incense, to which it was taken as to a warehouse, we conclude that the ballast was the result of ships laden with light incense which would requiring balancing. The concentration of Yemeni ballast in Egypt suggests a maritime route for incense. It would have travelled up the Red Sea, across the desert to the Nile thence to Alexandria from where it would travel to the major cities of the Mediterranean. The seaways would have been considerably easier and more ecomomic than the overland caravan route along the length of the Arabian peninsular to Gaza discussed by Pliny ( Natural History , 12, 32). The question now remains which was the more important. And this is something only archaeology can attempt to answer, which must be a subject for future research.

Of course the incense trade cannot be studied in isolation. Sunil Gupta argues partly from the little known ancient Indian economic treatise, the Arthasastra , and from his own work at Kamrej, that frankincense exports from the Hadramawt stimulated need for reciprocal supplies in a burgeoning economy. Noting significant quantities of Indian wares found on sites such as Khor Rori, Qana and, to some extent, Egypt, he concludes that the balance of payment problem may have been partly met by an increased export to Arabia of Indian goods such as cereals, sesame oil, cloth and iron. He sees the situation as analogous to the British substitution of opium for gold, in the purchase of China tea during the 19th Century. The ports of southern Yemen were pivotal in this economic activity. At the centre of the incense trade lies Qana and we are privileged to include a chapter by Alexander Sedov contributing an important new synthesis of the trading activities of the port based largely on his own analysis of the ceramic finds from recent excavations. He gives a fully documented account of the site: structures, stratigraphy, pottery and coins followed by an evaluation of their significance in the study of incense. Particularly striking is the discovery of incense warehouses at Qana, some with the precious commodity still in them. He also gives a valuable account of the Yemeni island of Socotra which was a source of aloe, frankincense and cinnabar. Finally he discusses the role of Khor Rori in Oman. In each case the starting point is his own original research, giving a valuable resum of the findings of the most recent archaeological research in these regions. Incense is not seen in isolation but as part of a far reaching trade network evidenced by pottery and particularly amphorae from Italy, Rhodes and later Aqaba in Jordan. The incense trade can now be seen in its broader perspective.

Somaliland was also an important production area as Caroline Singer emphasises. In Chapter 7 we examine this in relation to Aksumite Adulis, now in Eritrea. It is suggested on the basis of literary sources backed by some tentative archaeological evidence, that Adulis could have been an intermediary, shipping aromatics northwards to Alexandria and Ayla (Aqaba). Recent fieldwork has resolved the question of the whereabouts of the Aksumite harbour of Adulis and of Adulis of the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea. We include a brief resum of the main findings of this recent Eritro-British project.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade»

Look at similar books to Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Food for the gods : new light on the ancient incense trade and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.