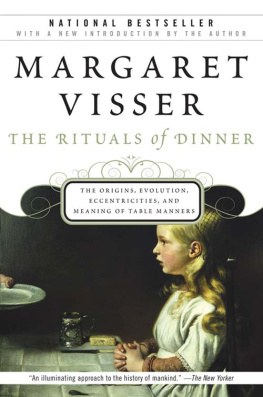

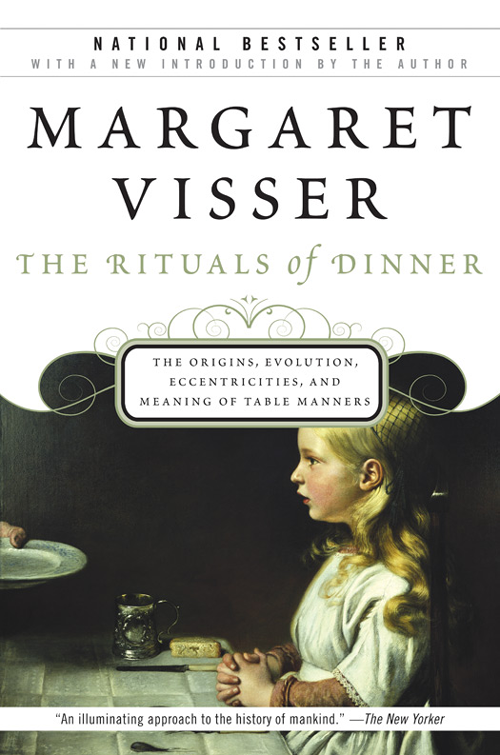

Margaret Visser

The Rituals of Dinner

THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTION, ECCENTRICITIES,

AND MEANING OF TABLE MANNERS

For Emily and Alexander

T HIS book is a commentary on the manifold meanings of the rituals of dinner; it is about how we eat, and why we eat as we do. Human beings work hard to supply themselves with food: first we have to find it, cultivate it, hunt it, make long-term plans to transport and store it, and keep struggling to secure regular supplies of it. Next we buy it, carry it home, and keep it until we are ready. Then we prepare it, clean it, skin, chop, cook, and dish it up. Now comes the climax of all our efforts, the easiest part: eating it. And immediately we start to cloak the proceedings with a system of rules. We insist on special places and times for eating, on specific equipment, on stylized decoration, on predictable sequence among the foods eaten, on limitation of movement, and on bodily propriety. In other words, we turn the consumption of food, a biological necessity, into a carefully cultured phenomenon. We use eating as a medium for social relationships: satisfaction of the most individual of needs becomes a means of creating community.

Table manners have a history, ancient and complex: each society has gradually evolved its system, altering its ways sometimes to suit circumstance, but also vigilantly maintaining its customs in order to support its ideals and its aesthetic style, and to buttress its identity. Our own society has made choices in order to arrive at the table manners we now observe. Other people, in other parts of the world today, have rules that are different from ours, and it is important to try to comprehend the reasoning that lies behind what they do if we are to understand what we do and why.

For in spite of the differences, table manners, all things considered, are remarkably similar both historically and the world over. There is a very strong tendency everywhere to prefer cleanliness or consideration for others or the solidarity of the dining group. Ritual emphases on such matters are occasionally highly idiosyncratic. But most rituals with these meanings have a good deal in common, and when people do things differently they usually do them for reasons that are easy to understand and appreciate. Sometimes, for example, festive diners are expected to eat a lot. Feasts are exceptional occasions, and a great deal of work has gone into them: the least a guest can do is show enjoyment. Fasting beforehand may very well be necessary, and exclaiming with pleasure, smacking ones lips, and so on might be thought both polite and benevolent. Other cultures prefer to stress that food is not everything, and guzzling is disgusting: restraint before the plenty offered is admired, and signifying enjoyment by word or deed is frowned upon. Sometimes it is correct to be silent while eating: food deserves respect and concentration. In other cases one must at all costs talk: we have met not merely to feed, but to commune with fellow human beings. Even though we come down on one side or the other, we can sympathize with the concerns that lie behind the alternative choice of action.

The book is organized neither chronologically nor by culture and geography. I have elected rather to travel, both in space and in timeto choose examples of behaviour from other places and periods of history wherever they throw light, whether by similarity or by difference, upon our own attitudes, traditions, and peculiarities of behaviour. My aim has been to enrich anyones experience of a meal in the European and American tradition, to heighten our awareness and interest on the occasions when we might be invited to share meals in other cultures, and to give the reader some idea of the great range of tradition, significance, and social sophistication which is inherent in the actions performed during the simplest dinner eaten with family or friends.

The two opening chapters deal with basic principles. The first of these considers why it is that every human society without exception obeys eating rules; what ritual is and why we need it at dinner (cannibalism, for instance, is found to conform to strict laws and controls); and the meaning of feasting and sacrifice. The second chapter is about how people the world over teach children table manners, and how our own culture evolved its dinner-time etiquette. We have insisted more and more strictly on bodily control; and we have often used table manners to serve class systems and snobbery.

Chapter Three starts to take us through a meal eaten in company with others: the etiquette of invitations, the laws governing hosts and guests, behaviour on arriving at somebodys house for dinner, and the seating arrangements. The dinner we are about to share is a sit-down meal with friends, some of them intimate and some only slight acquaintances; the party takes place in the hosts house. Such a meal invariably includes comfort, risk, and significance, complexity, plotting, setting, and dramatic structure enough to supply ample material for a book-length commentary. We necessarily leave out not only the specific menu of our meal, but also the characters and stories of individual guests, their preferences, conversation, and idiosyncrasieseverything that makes each dinner party different from every other. In this book we shall be concerned merely with conventions, where they come from, and what they signify.

Dinner Is Served in the course of the long central Chapter Four. We watch each other eat a meal, from first bite to leaving the table and then the house for home. In order to understand our manners, we must consider what they might have been and are not. Sitting on chairs round a table to eat is not necessarily the way its donewhy then did we decide to do it? How do people behave who do without chairs? When and why did we stop eating with our hands, what does that decision tell us about our attitude to food, and what difference has it made to our eating behaviour? How do we account for tablecloths, candles, serving spoons, wineglasses, and for ceremonials such as saying grace or toasting? Even though many people may eat formal sit-down dinners rarely or not at all, the fully deployed formal meal remains the paradigm from which other food events borrow their symbols, sequences, and categories. Picnics, airline dinners, cocktail parties, and fast-food breaks are among such variants discussed in the book. They reveal, in the very changes rung or in their choice of quotations from the original, many of our attitudes towards food rituals.

Restaurant meals are an immensely complex subject that I have had, regretfully, to treat only tangentially. For the most part, eating in a restaurant requires the same table manners as those expected at a fairly formal dinner at home. (Readers interested in pursuing the social issues raised by the topic might start with the books by J. Finkelstein, and G. Mars and M. Nicod, listed in the Bibliography.)

The reason why I chose to describe a formal meal is its fullnessit covers the broadest range of activitiesand its intricacy. Informality, as the word tells us, presupposes at least some concept of a formal model, and informal behaviour is to be understood in the first place by considering the rules that it disregards, and then seeing what rules it invariably retains.

Chapter Five is a detailed treatment of bodily propriety when eating: control above all of the mouth, but of the rest of the body as well. It is at this point that pollution avoidances during meals are briefly discussed. The final postscript addresses itself to the so-called falling off of manners and ritual in modern Western society; it considers why we are so determined to be casual, and whether we are in fact ruder than we used to be.