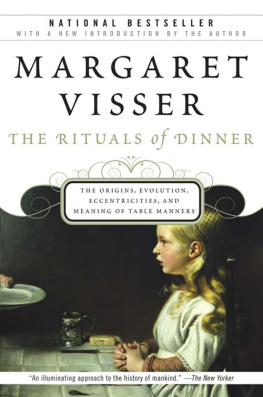

MUCH DEPENDS ON DINNER

Since Eve Ate Apples

MARGARET VISSER

Copyright 1986 by Margaret Visser

Introduction to the Second Edition copyright 2008 by Margaret Visser

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

First published by McClelland and Stewart Limited, Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Visser, Margaret.

Much depends on dinner.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Food habits. 2. Dinners and dining. 3. Food

habitsEngland. 4. Dinners and dingingEngland.

5. FoodHistory. 6. EnglandSocial life and customs.

I. Title.

GT2860.V57 1987 394.12 87-257

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9646-0 (e-book)

Illustrations by Mary Firth

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

FOR MY PARENTS

John and Margaret Barclay Lloyd

Special thanks are for Colin, Emily, and Joan, and for Pat Kennedy, Emmet Robbins, Nada Coni, Norma Rowen, and Alan Koval. Pierre Berton encouraged me to write this book when I had just begun work on it, and so did all the staff of CB C Radios Morningside, especially Don Harron, Richard Handler, and Peter Gzowski. Vesna Vukov kindly undertook to check the chemistry sections. I would also like to thank my editors, Ramsay Derry and Sarah Reid, and Jan Walter at McClelland and Stewart.

Introduction to the Second Edition

WRITING THIS BOOK was easy, because the subjects time had come. In the early 1980s it suddenly seemed essential, in order to look at ourselves anew, to take advantage of the point of view that food provides. Why do we eat what we eat, and where does it come from? What does each ingredient do for us, mean to us? What human choices and efforts have been made in order for it to land on our plates? What should our food bring to mind if we are to be fully aware of ourselves, our history, our politics, and our surroundings? These were clear and insistent questions. My own need to find out the answers, and the research I undertook to satisfy it, resulted in Much Depends on Dinner. The book is about food, but it is first and foremost about ourselves.

Since this book first appeared there has been an explosion of writing about food. Just why we have become so fascinated, and so recently, by this subject remains a matter for reflection and further understanding. Human beings have always loved eating, of course. It is the great flood of writing about it that is new, and typical of our own culture. Food used to be thought too low a subject for intellectual rumination, a merely animal pleasure, a necessity that, once we had secured sufficient supplies of it, was too obvious and too crude for discussion in public. True, eating was introduced into plays and stories, but only incidentally, or when a dinner scene was useful for dramatizing the characters of its participants or to move the plot along. Many climactic actions in fiction occur at the dining tablein Shakespeare for example, or in Dickensbut the food itself is almost never the point of any scene. It is mentioned, and the characters eat it, as they wear clothes or converse, largely in order to make themselves convincingly real. Nowadays, people conduct vast amounts of research into the eating habits of the Elizabethans or the Victoriansscholarship that the people under investigation would have found deeply curious, even disturbing. Who might we be, to be so interested in what they ate?

Eating, in earlier times as now, was part of family togetherness, of festivities of all kinds, and every town had its gastronomic specialties. But people did not normally think any of these subjects worthy material for essays or book-length treatment. There were exceptions, but they seem to us surprisingly few, as any modern food historian will attest. Recipe books were published, especially from the eighteenth century on, as instruction manuals. These were commonly assumed to be the only writings about food that could conceivably interest the public. I remember proposing Much Depends on Dinner to a publisher who rejected it on the grounds that I had written about food without offering any recipes.

Today, food writing has become a literary genre. Entire books are written on single food itemson mustard, on strawberries, on oysters. Novels are constructed around recipes and eating behaviour. Memoirs can turn out to be largely chronicles of food eaten. Recipe books themselves, with added commentary and narrative, have become bedside reading material. Recipe compilers unhappily suspect that their work is seldom actually used in the kitchen.

We are members of a consumer culture. Consume is from a Latin word that meant destroy, waste, or exhaust, and then devour. Consumption in English now refers to the human activity of taking what we want from nature. We have been culturally induced to be fascinated by all the thingsnot only the foodsthat we buy and consume. We go on to question their significance, to notice their image-enhancing power. And we feel a compelling need to put all this into words, to comment on it if we can. The reason includes our awareness that things unnoticed, meanings taken in subliminally, can both influence our behaviour and suggest information about ourselves to others in ways we have not consciously chosen; we do well, then, to keep our awareness and our defences up and ready.

Eating is not only biologically necessary; it is socially significant as well. A medieval king would be assured by elaborate ceremonies performed before dinner by food tasters (whose job it was to die if the food turned out to be contaminated) that he was not being poisoned. He was flattered by the attentions ritually paid to his safety, by the open recognition that his health was of enormous significance to those around him. Food is inevitably both physical and cultural. It feeds, but it also expresses human intentions, hierarchies, social strategies, and relationships. This fact is as true today as it ever was. But the practice, now common, of recounting human history through the medium of food focuses our attention on the hard work and inventiveness that are always required to ensure a regular supply of nutrition. This interest is part of a modern democratic impulse, a preference for concentrating on the essential contributions made by ordinary people rather than on the prestige of kings.

The story of food includes greed and selfishness when those who are already well fed keep and will not share their plenty; the generosity and delight that eating can express; the art with which food is prepared; the beauty of the fruits of the earth in themselves and in their presentation; the power of eating together to unite people, to reconcile themor to rouse them to violence. Food constantly draws mythology to itself, as well as imagination and creativity. The spectacles of human ingenuity and obsessiveness that it affords are admirable, and also frequently amusing: the frantic posturings of advertising, the careful rejections of specified foodstuffs for cultural reasons, the quasi-sacred status of spaghetti or beer or rice where they are central to whole systems of civilization. All this has been revealed in our day to be crucial to understanding human behaviour in general.