Except where otherwise indicated, photographs are by the author.

PREFACE TO EBOOK EDITION

Since Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings was first published, its goal to foster deeper understandings of this regions rural heritage has become increasingly relevant as more historic farm buildings face being lost. Indeed, many of these vulnerable barns offer valuable information about the history of rural life through their various features and evidence of past uses. Furthermore, when such buildings are examined in conjunction with written historical records, fresh perspectives may emerge about the history of rural New England. Certainly the greatest source of this physical evidence is the remarkable library of artifacts scattered across the New England landscape that may be read by anyone with an understanding of the basic language of farm building forms and features as discussed in this text.

But those who seek to read evidence of this history from the land must be forewarned: the stock of surviving examples spread across the New England rural landscape is dwindling. Some losses of important local rural landmarks have caused great public alarm, but perhaps an even greater concern has been the quiet disappearance of so many less-celebrated examples of older vernacular farm buildings. And with their passing, so many stories have been lost.

Along with a growing recognition of the value and vulnerability of this legacy, important questions arise about how fast these heritage resources are disappearing. This rate of loss has been difficult to assess, but recent initiatives have been launched at local, state, and national levels to assist with the recognition and documentation of historic barns and farm buildings. Indeed, one of the most encouraging recent movements has been the establishment of local and statewide barn census programs that engage volunteers to help identify existing examples of the regions rural heritage for the benefit of future generations.

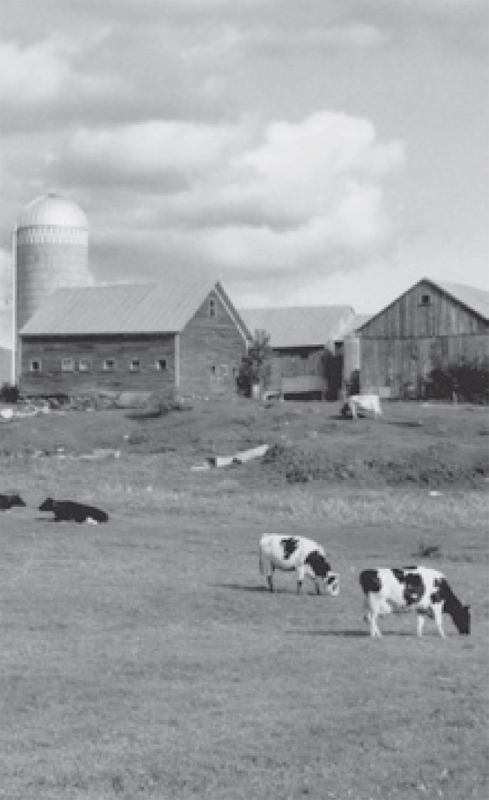

Reviewing the nearly two hundred images of New England farm buildings included in this ebook edition, the author is struck with a fresh realization of how many older farm buildings standing in the 1990s were then no longer in active agricultural use. Many of these were abandoned survivors from past eras, whose existence could be credited more to their stubborn durability than to continued stewardship by their owners.

Some of the barns that were originally photographed for this book probably no longer exist today. Although this question has not been thoroughly investigated, neglect was undoubtedly the main factor that contributed to these disappearances. Without continued use, buildings inevitably tend to suffer from lack of care. Over time, small maintenance needs that are ignored and unremedied tend to grow into major deterioration problems. The small roof leak, for example, that might have been quickly fixed with a small patch may over several years cause drips of water inside, which in turn may cause the decay of major structural timbers. After several decades of such deferred maintenance, the extent of the damage can lead to increasing repair costs, and eventually to unsafe conditions and structural failures.

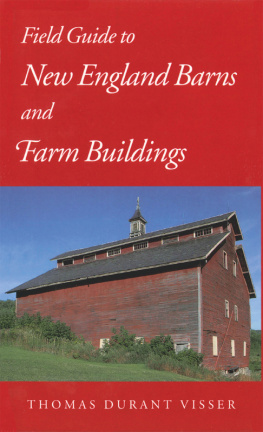

Such is the example of the red, monitor-roofed dairy barn that graces the cover of this ebook. This landmark building in Richmond, Vermont, has since been saved through the concerted efforts of local volunteers, nonprofit organizations, state agencies, and federal support, but only after its deteriorated structure was entirely disassembled and carefully reconstructed with mostly new materials on an adjacent site for a new purpose. This accomplishment was certainly justified, but it can hardly serve as a model for the treatment of the many thousands of other underutilized historic farm buildings in New England. Instead, incremental maintenance and adaptive reuse are the key approaches to barn preservation.

Perhaps the most encouraging preservation efforts have been by farmers who have found new agricultural uses for their older farm buildings. In some areas, this has involved shifting away from large-scale farming in favor of various specialized, small-scale farming endeavors.

For many other historic barns and farm buildings, whether associated with agricultural activities or not, storage may be their most suitable use. Nearly all of the small barns and outbuildings studied for this book were being used for some type of storage. Even for scattered barns now in suburban settings or adjuncts to residential properties, various storage uses and incremental repairs may best sustain their ongoing existence.

For some historic New England barns listed on the National Register of Historic Places, federal reinvestment tax credits have covered a portion of the rehabilitation costs for work done in accord with federal historic preservation standards. With grant support from nonprofit preservation organizations, some barn owners have hired architectural conservation experts to conduct condition assessments that diagnose deterioration problems and recommended prioritized conservation work. Some state historic preservation offices also have offered grants to help offset costs of urgent major repair needs for important historic barns.

Through such various preservation efforts, many historic farm buildings continue to provide practical uses, while offering future generations insights into the rich heritage of rural New England.

August 2012

T.D.V.

PREFACE

The purpose of this Weld guide is to help residents, travelers, and scholars discover the rich rural heritage of New England before the surviving architectural evidence of this history is lost. As a scattered collection of artifacts, historic farm buildings can provide glimpses into the regions past. By providing clues for deciphering the many layers of history spread over the rural landscape and by showing how farm buildings fit into broad regional patterns, I hope to help observers see beyond a simple then and now nostalgic view of the past and instead realize the wonderful insights that can spring from an understanding of the evolution of our rural heritage.

While Weld guides to wildflowers use blossom color as the key to identify plant species, this field guide sorts vernacular farm buildings by their type, based on their form and use. Recognizing that these vernacular buildings are products of a diverse, complex, and fluid culture, this guide intentionally avoids using names that imply a direct ethnic or geographical lineage. (An exception is the commonly used English barn type name.) For this reason, the names of farm building types offered here tend principally to be descriptive of form and use.

The book is the product of the field research conducted in the six New England statesMaine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. To gather a representative sampling of the surviving physical evidence, the following methodology was developed. Within each state specific representative areas were selected for intensive study based on their association with past farming activities and the amount and integrity of the surviving architectural evidence of this history. For these intensive studies, windshield surveys were conducted along the highways and backroads of the areas. Both typical and distinctive examples of farm buildings and their characteristics were noted and photographed. The thousands of photographs obtained through this field research provide the primary source of comparative evidence and the bulk of the images for this work. Although the captions for some of these photographs provide the exact date of construction when known, many of the dates are approximations based on physical evidence and the general historic context, rather than on documented historical information. A margin of error of about ten years should be assumed when the term circa is used in these captions.