F irst, I'd like to acknowledge my parents, Peter and Sarah, and my brother Amos. Second, I'd like to thank Steven L. Mitchell, the editor-in-chief of Prometheus Books, both for recognizing (along with others at Prometheus) the merit of a modern biography of Benjamin Graham and for his editorial assistance with The Einstein of Money. I would also like to thank Brian McMahon, Jill Maxick, Catherine Roberts-Abel, Melissa Shofner, Jade Zora Ballard, Lisa Michalski, and the entire staff at Prometheus Books for help with various aspects of this project. Mindy Flanagan, manager of business programs for international students at UCSD Extension, also deserves thanks for facilitating the internships of Jisun Park, Yumi Nishizawa, and Christine Xie. The aforementioned students assisted with research for this project, and Ms. Park deserves special acknowledgment for her help with some of the current investment examples. Yuki Kato, another intern from that program, assisted with promotional efforts for this project.

I'd like to thank Warren Buffett for granting me an interview in which he provided invaluable insight into Benthe man who is still Buffett's primary business/investment mentor (and a dear friend for whom he still holds great admiration and affection). I would also like to extend my gratitude to Mr. Buffett's son (and the acclaimed musician) Peter Buffett for his pivotal role in connecting me with his father. I am also greatly indebted to Graham's children, Benjamin Graham Jr., MD, and the late Marjorie Graham Janisboth were most generous with their time, and Dr. Graham also provided some outstanding interview contacts and family photos. Marjorie's daughter Charlotte Reiter, as well as Charlotte's cousin Pi Heseltine (another of Graham's granddaughters), provided excellent insights and photos for which I'm very grateful.

I'd also like to extend special thanks to other personal and professional associates of Graham who shared their remembrances with me: Charles Brandes; Irving Kahn; Thomas Kahn; Dr. Robert Hamburger and his wife, Sonia; the late Dr. Bernie Sarnat and his wife, Rhoda; and the late Professor Fred Weston of the UCLA Graduate School of Business. Their interviews provided a rich layer of additional detail and anecdotes regarding Graham's towering intellect and eccentric personality. I would also like to thank the other prominent value investors and academics who were interviewed for this project. These include Mark Russo, Pat Dorsey, Professor Richard Roll, Andrew Kahn, Mitsunobo Tsuruo, Hideyuki Aoki, Robert Hagstrom, David Poulet, and Raphael Moreau. Most of those interviews were made possible by the 2011 Value Investor Conference organized by the renowned Buffett/Berkshire expert Robert Miles.

I would also like to thank my friends and colleagues: Robert Bell, Nathan Stinson, Jeremy Tiefenbrun, David Kanoa Helms, Russ Weinzimmer, Hannah Bui, Max Rizzuto, Simon Eisner, Tom Flaherty, John Friar, Ieden and Harlan Wall, Jon Davis, Elizabeth Shulman, Ron Hall, Lynn Whitmire, Cheri Hill, Mary Anne Andrews, Sergio Fernandez, Shefali Kumar, Karen Messenger, Michael Weitzman, and the late Eric Leonard. I would also like to acknowledge my Uncle Bob, Aunt Monica, Aunt Eliane, Mark and Jennifer, Al and Daphne, and other extended family members. As well, Frank Scatoni deserves thanks for encouraging me to follow through with a modern biography of Graham. Last, but certainly not least, thanks to Benjamin Graham himself for having left an extraordinary legacy that is rich in both financial wisdom and human insight.

NOTES

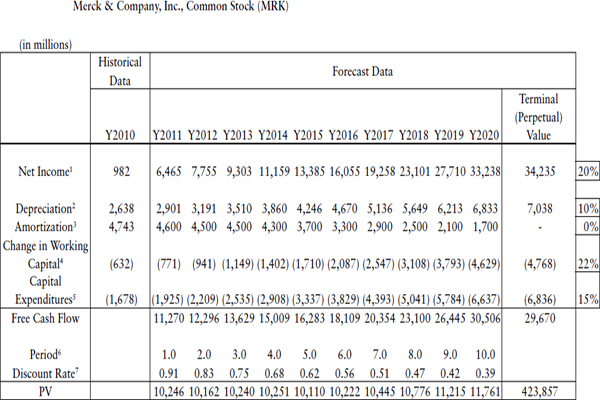

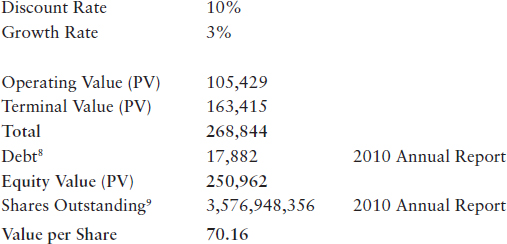

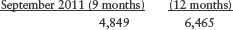

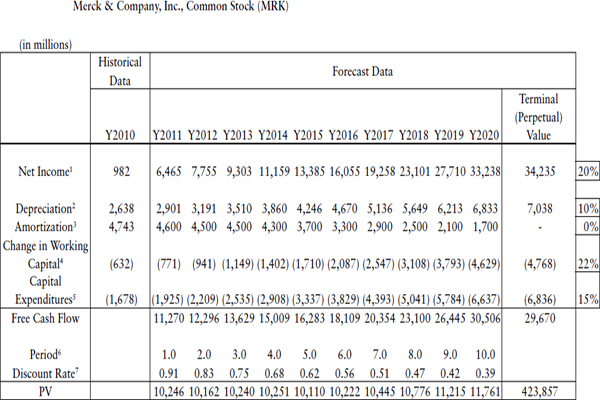

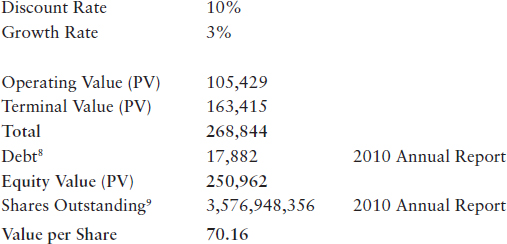

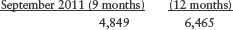

1. 2011 estimated net income is annualized from the 2011 Third Quarter Report.

Net income from 2012 to 2020 is forecasted by employing the average growth rate of the past five years (2010~2006) of net annual income figures.

Net income for terminal value assumes a rate of 3 percent (average US GDP rate).

2. The 2010 real (i.e., historical) depreciation figure is from Merck's 2010 Annual Report.

Estimated depreciation is forecasted by employing the average growth rate of the past five years (2010~2006) of annual depreciation figures.

Depreciation for terminal value (perpetuity) is calculated using a rate of 3 percent.

3. The 2010 real amortization figure is from Merck's 2010 Annual Report.

Estimated depreciation from 2011 to 2015 is from the 2010 Annual Report.

Estimated depreciation from 2016 to 2020 deducted $400 million every year.

Amortization for terminal value is calculated using a rate of 3 percent.

4. The 2010 real working capital figure is from Merck's 2010 Annual Report.

Working capital from 2012 to 2020 is forecasted by employing the average growth rate of the past five years (2010~2006) of annual revenue figures.

Working capital for terminal value is calculated using a rate of 3 percent.

5. The 2010 real capital expenditure figure is from Merck's 2010 Annual Report.

Estimated capital expenditures are forecasted by employing the average growth rate of the past five years (2010~2006) of capital expenditure figures.

Capital expenditures for terminal value are calculated using a rate of 3 percent.

6. Assume that free cash flow occurs at the end of the year.

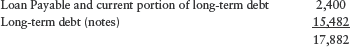

7. Apply 10 percent discount rate (since Merck is a large-cap company).

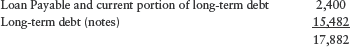

Apply interest-bearing debt figure from the 2010 Annual Report

The figure for the number of shares outstanding is from the 2010 Annual Report.

B enjamin Grossbaum was born in London, England, in 1894, toward the end of the reign of Queen Victoria. Grossbaum was his legal surname until his family Americanized it to Graham roughly twenty-three years later (for the sake of clarity and consistency, our subject will generally be referred to as Graham throughout the book). His father, Isaac, was born in Britain and was proud of his British upbringing (a pride that, apparently, was never diminished by the family's subsequent emigration to the United States) while his mother, Dora, originated from Poland. Isaac Grossbaum, along with his five brothers and his father, Bernard, owned and operated a business that imported china, bric-a-brac, and related merchandise from Austria and Germany to the United Kingdom. The Grossbaums were able and industrious merchants, Isaac being especially gifted in this regard. The Grossbaum family was also strictly orthodox in its practice of the Jewish faith.

Isaac was one of eleven children. Among the devoutly religious (Jewish or otherwise), such large families were (and are) not unusual. What was somewhat unusual, even in an orthodox context, was the extent of discipline that Isaac's father imposed upon his children. Because he was so fearful of any ungodly influence, he enforced a draconian code of conduct upon his household so severe as to prohibit such sinful debauchery as whistling! According to his However, considering that Benjamin grew up in a home where he was exposed to French lessons and other secular/non-Jewish activities, it seems that, while officially orthodox (at least while Isaac was still alive), the family Graham was born into was somewhat less pious than that of Bernard Grossbaum.

Next page