For Dad. Thank you for passing on your knowledge of the syrup industry and instilling in me your tireless work ethic.

S.A.

For Mom and Dad.

A.K.A.

Thank you to Sarah Dorison and Brenda Buck for reading and editing our manuscript, and to Deb Burns and Sarah Guare, of Storey Publishing, for their patience and encouragement.

Andersons Maple Syrup, located near Cumberland, Wisconsin, has been a family-run business since 1928. There are about 2,500 sugar maples in our family sugar bush, plus another 2,000 maple trees just 5 miles down the road.

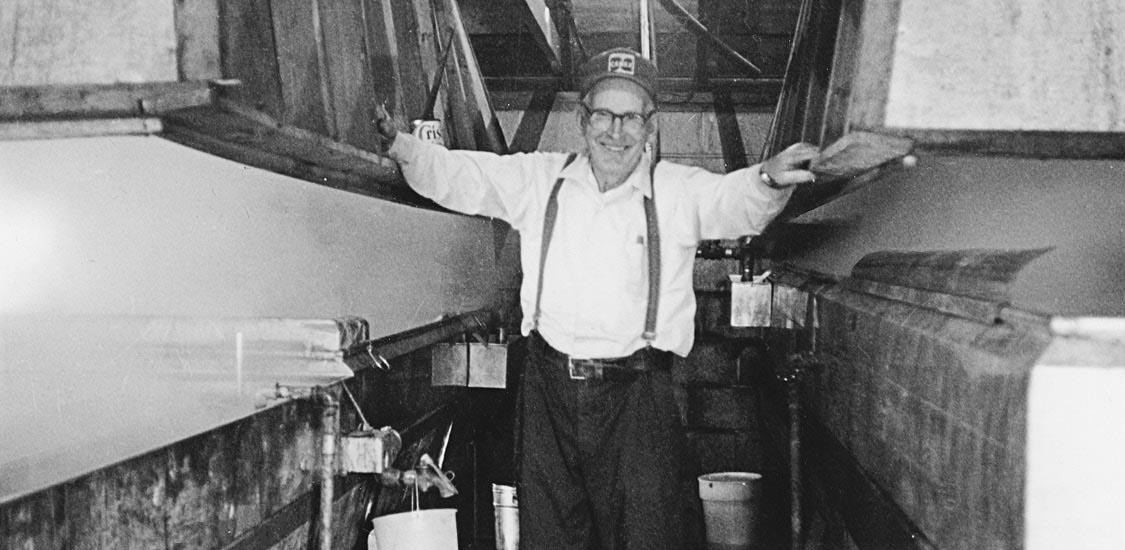

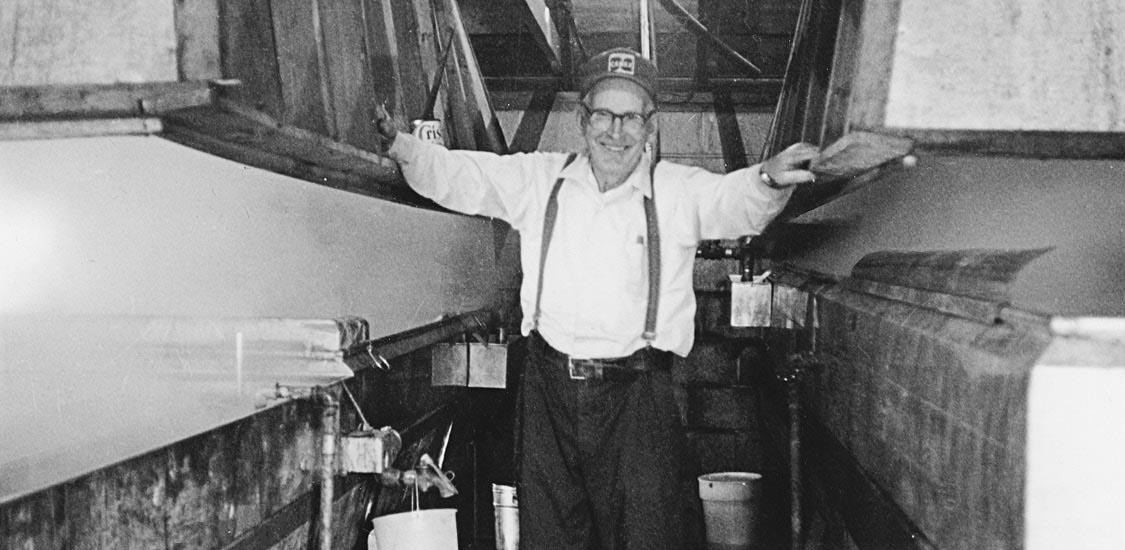

Steves family purchased the homestead in 1928, and as for many Wisconsin families, the main source of income was dairy farming. Paul Anderson, Steves grandfather, inspired by childhood memories of sugar making with his father, began tapping trees and making just enough maple syrup for his family and neighbors to enjoy. He collected sap with metal buckets and spouts, and a horse and wagon carried it to the sugarhouse.

Paul Anderson cooks syrup on two 6-by-16-foot Leader Evaporators.

There he boiled it to perfection on an open pan over a handmade stone and cement arch. Paul purchased the first evaporator for the family in 1947 for $680 a brand-new 5-foot by 16-foot King. As he sold more syrup, he was able to rely less and less on farming for income. In 1957 he sold the last of the dairy cows and turned to syrup making and syrup equipment sales full-time.

Pauls son, Norman, grew up helping his father care for the sugar bush and learning how to produce sweet maple syrup, and eventually Paul and Norman were running the business together. They began selling syrup-making equipment in 1954, when the family became a Leader Evaporator dealer. Andersons is still a Leader dealer today.

Originally, equipment was delivered from Leaders Vermont headquarters to the North Woods of Wisconsin by train. The train came through a nearby town and parked on a railroad siding, and Paul and Norman unloaded the train car there. Today semi-truck loads of equipment and pallets of syrup go directly in and out of the warehouse, located across the road from the sugarhouse where Paul made syrup.

Peak Production

In the 1970s we were at peak production, tapping almost 18,000 trees with buckets on various pieces of land across Wisconsins North Woods. Norman ran the business at this capacity for about 10 years while he expanded the company and increased syrup and equipment sales. Norman hired the companys first full-time employee in 1974.

By 1980 we were able to sell far more syrup than we could produce ourselves. Norman began purchasing syrup from other local producers, who then bought syrup-making equipment from Norman. Andersons Maple Syrup still operates on this cooperative model. Normans son Steve sells equipment and buys syrup from many of the same producers his father did, as well as many others.

With fewer than 10 employees, Andersons is still a small, family-run business, but the company now has a national, even global, presence. Steve has increased syrup sales and taken the Anderson label from a regional family staple to a national syrup brand. We ship syrup to customers as far as Asia. We also have an extensive syrup equipment business with a showroom and a website.

Steve has added technological advancements to the business by utilizing some automated equipment for packaging and by modernizing the way sap is collected in the sugar bush. These days you wont find a single bucket hanging in the woods in the Andersons sugar bush. We use a modern, tree-friendly tubing system with vacuum, which moves the sap directly to a collection site. From there the sap is transported to the sugarhouse for cooking and bottling.

Our family is proud to participate in Wisconsins Forest Crop Law program and Conservation Reserve Program. These are both voluntary efforts for agricultural landowners designed to protect natural habitats and preserve them for future generations.

Conservation Programs

The Forest Crop Law (FCL) program, part of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, encourages long-term sustainable management of private woodlands. In exchange for participating in FCL, landowners pay reduced property taxes.

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) is a voluntary USDA and Farm Service Agency (FSA) based program. This program, available to agricultural landowners, encourages members to use portions of their land to further conservation efforts. Participants in CRP are provided with yearly compensation.

Our Guide for You

We created this guide as a quick reference for beginning syrup makers. We want to encourage those interested in syrup making to tap their maples, so that the legacy and art of this rustic tradition will continue well into the future.

Weve included what we believe to be the easiest and most straightforward methods for harvesting and cooking sap and for filtering and bottling finished syrup. There are many variations in the way you can gather sap and make syrup, and innovations are constantly improving the maple industry, but the information in this guide is a good place to start.

We hope you find this guide helpful and that you have continued success in syrup making!

Chapter 1

The History of Maple Syrup

The maple syrup industry has evolved greatly since Native Americans discovered how to make pure maple syrup. Vast improvements have been made in sap collecting and cooking methods and syrup-making equipment. The basic process remains the same, however: Boil sap to evaporate water and make sweet, pure maple syrup.

Native Americans Discover Maple Syrup

It is generally agreed that Native North Americans were the first to make maple syrup. Various legends describe how maple syrup was discovered:

The sap-sicle. The branch of the maple tree broke during the late winter and sap flowed out of it. The dripping sap froze into an icicle. The repeated thawing and freezing of the sap-sickle concentrated the sugars and made the icicle unusually sweet. A Native American tasted the icicle. He or she noticed that the liquid had a distinct sweetness to it and deduced that it had come from inside the tree, rather than from melting snow.

Hatchet job. Another legend involves a Native American hunter who, when he arrived home from an unsuccessful hunt, threw his hatchet at a maple tree. The hatchet stuck in the tree and created a wound. The sap that flowed from the wound in the tree collected in a cooking container that the hunters wife had placed on the ground beneath the tree. The next day the hunters wife mistakenly thought her husband had filled her container with water and she began to cook with it. When they tasted their meal, they discovered that it was sweet! After examining the tree and discovering the sap flowing from it, they realized what had happened.

Substitution. A woman was cooking supper for her husband. When she became distracted by her quillwork, her boiling pot went dry. She did not have time to melt snow so she poured in some maple sap that she had collected for drinking. Their meal had a delicious sweetness to it. Her husband enjoyed the meal so much, it is said that he licked the pot clean!