New York

To my children, Tom and Lily

Contents

Introduction

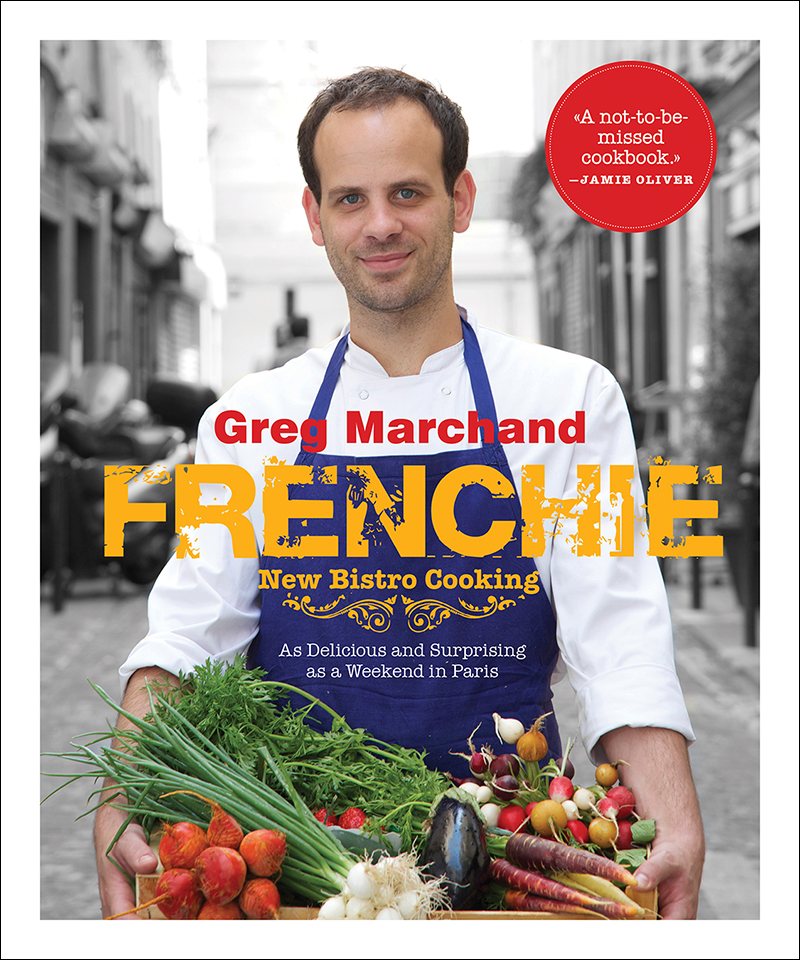

When I worked at Jamie Olivers restaurant Fifteen on Old Street in London, he nicknamed me Frenchie because I was the only French person in the kitchen. The nickname stuck (new members of the staff never even learned my real name), and thats how it came to pass that my restaurant in Paris is called Frenchie.

At Fifteen, every year wed hire fifteen kids from disadvantaged backgrounds and train them in the kitchen. I identified with these young apprentices, having had my own share of troubled times. Id started to cook when I was fifteen, in the orphanage where I grew up, in Nantes.

The chef was off on weekends, and I was more than happy to volunteer to cook: it gave me a break from the craziness of the orphanage courtyard. The first dish I ever made was escalope normande, veal with mushrooms and cream. Although it was probably poorly executed, the joy it generated in the other kids was enough to persuade me to enroll in cooking school. To this day, pleasing people, seeing the smiles on their faces when they take their first bite of a dish I have made, fills me with pleasure.

I entered cooking school in Brittany at sixteen, sporting long hair, a skull ring, and a Metallica patch on my jean jacketI thought I looked so cool! But the teachers didnt agree. I was quickly dispatched to the barber and then to buy a couple of cheap suits, some black socks, and a pair of black shoes. My love affair with hard rock went the way of the long hair.

I had a lot to sort out in my life back then. That I got through my studies was nothing short of a miracle, but I did graduate, having learned the basics of French cuisine, restaurant health and sanitation rules, and the ins and outs of the hospitality business. With good luck, I soon landed a job in London with David Nicholls at the Mandarin Oriental in Knightsbridge. It was my first experience working as part of a large brigade with very high standards. I realize now that my passion for cooking was born then and there: it was the first time in my life that I felt part of somethinga clan, a posse, a family, all centered on cooking. I was happy to get up and go to work, and I learned something new every day. That was my best cooking school ever. And I loved the energy of London, the curries served on Brick Lane and the full English breakfast at the greasy spoon where we would go on our days off, after a night of drinking.

When the restaurant closed for renovation, I got myself transferred to the Mandarin Oriental in Hong Kong, where I worked at Jean-Georges Vongerichtens Vong. The menu was a perfect fusion of French and Asian cooking, foie gras and mango, duck and tamarind, and all kinds of crazy things I had never seen before. I had a blast in Hong Kong, but I had to return to London to be part of the reopening team there. We had a brand-new kitchen with a wok, a tandoori oven, and a wood-fired oven. It was awesome: I was cooking new dishes and discovering new ingredients every day. But I didnt get on very well with the new head chef. One day he verbally abused me so badly that I packed up my knives, handed him my apron, and left.

Years of London weather had left me yearning for the sun, so I flew off to Andalusia and worked on the beach in a chiringuito (beach bar), making fresh fish a la plancha, octopus a la gallega, tortillas, and all sorts of tapas. Cooking barefoot in the sand felt good, but I needed more of a challenge. That test came in the person of Arthur Potts Dawson, previously a sous chef at The River Caf in London, who was opening a restaurant in Marbella. I became his sous chef, and the food we did there was inspired by The Caf: simple regional Italian cuisine made with great fresh ingredients. It was my first real exposure to Italian cooking. We even had a wood-burning oven and turned out great pizza. What a year!

Then Arthur was offered a good position in London, where I followed him. Thats when I landed at Fifteen, where I eventually became head chef. Its difficult enough to run a restaurant with a team of dedicated chefsimagine having a team of kids struggling with the simple idea of having to work every day! But we did very well, and when I see that most of them are now professional chefs, spread out around the world, it makes me proud. I also learned respect for ingredients from Jamies less is more approach, and I learned how to keep a business afloat and manage a staffall with the thought of opening my own place one day. But I wasnt ready, and New York beckoned.

Once I arrived in New York City, I tried out at a few restaurants, and when Michael Anthony, the newly appointed chef at Gramercy Tavern, offered me a job, I jumped at the chance to work there. My girlfriend (and soon-to-be wife), Marie, and I found a nice little apartment in Greenpoint, a Polish neighborhood in Brooklyn. When I came out of the subway, I felt as if I were in Warsaw, with everybody speaking Polish and delis selling Polish charcuterie and other specialties. I immersed myself in New Yorks rich melting-pot culture. Japan, Korea, Italy, and Mexico, to name a few, were all less than a forty-minute subway ride away, and it was a great inspiration to have products from all over the world so readily available.

On my days off, Marie and I would try different restaurants, from three-stars to little Chinese joints, from newly opened places to established older restaurants. Traveling farther afield, we ate our way through Chicago, San Francisco and the Napa Valley, Florida, and upstate New York. All these experiences gave me more and more ideas about what my own place could be like. Everywhere I went, I took notes in my little Moleskine book about what I found great in each place, from menu holders to the lighting to food, of course, as well as the organization of the dining rooms and menus.

My time in Spain was an advantage in the Gramercy Tavern kitchen. Although my Spanish was basic, I knew enough to be able to carry on a conversation with the many Hispanic staff members, which made my work easier. Working at the Tavern was a transformative experience. My food is still inspired by Michaels farm-to-table style, and my sense of hospitality is totally informed by the genius of Danny Meyer.

After a year, however, Marie learned she was pregnant. I was very excited about being a dad, but it happened much faster than wed planned. And we didnt have good health insurance, my visa was going to expire, and Marie had had trouble finding a suitable job. Yet I also felt ready: it was time to go home, after more than ten years on the road. I sadly handed in my notice, and we packed our stuff and flew back to Paris.

When we arrived there, in September 2008, we were jobless and almost penniless. We rented a tiny apartment in Montmartre and I applied for unemployment. I knew I had very little time to launch my project, as cash was running out and Marie was due in December. After exploring several different neighborhoods, I found a spot I really liked on an improbable, deserted cobblestoned street called rue du Nil, tucked away in the garment district. My friends thought I was crazy, but I loved the location. We were a few steps from the busy rue Montorgueil and Les Halles, the historic area known as the belly of Paris, home until 1971 of the great wholesale marketplace through which all the foods served in Parisian restaurants passed. It made perfect sense.