DEDICATION

To Dr G, I owe you everything.

CONTENTS

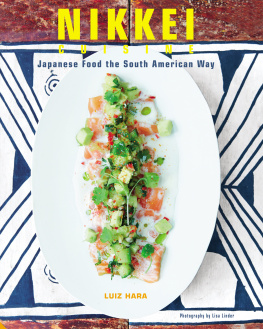

WHAT IS NIKKEI CUISINE?

Nikkei is derived from the Japanese word nikkeijin, which refers to Japanese people who migrated overseas and their descendants, including me and my family. Nikkei cuisine, therefore, is the cooking of the Japanese diaspora. Japanese migrants have found themselves in a variety of cultures and contexts but have often maintained a loyalty to their native cuisine. This has required local adaptation: the so-called Nikkei community has embraced a new countrys ingredients and assimilated these into their own cooking using Japanese techniques. So, Nikkei cooking is found wherever in the world Japanese immigrants and their descendants are. But, for historical reasons, two countries have had substantially more Japanese immigrants than most of the rest of the world Brazil and Peru. And it is these South American countries that are particularly noted for their Nikkei cooking.

Brazil has the largest Japanese population of any country outside Japan and it was there that my grandparents migrated and where I was born. Since their arrival, the Nikkei have made a tremendous contribution to agriculture, introducing a number of Japanese fruit and vegetable stocks to Brazil, as well as greatly improving the cultivation of native varietals; work that still continues. On arrival, the Nikkei had to adapt to a predominantly meat-worshipping nation but, because of the large numbers of migrants, they were quick to set up artisan production of tofu, soy sauce, miso (fermented soya beans) and even udon noodles to satisfy the needs of the newly arrived community. Peru has a smaller Nikkei population than Brazil, but since both it and Japan have a Pacific coastline (on opposite sides of the ocean) they share many fish species. With a stronger native agriculture and food heritage, Peru has been the crucible for creating a vibrant Nikkei cooking culture. Peruvian Nikkei dishes often use the maritime abundance brought to the coastline by the Humboldt Current, as well as the unique aji peppers, lime, corn and yucca, not to mention the more than 3,000 varieties of potatoes.

So, it is fair to say that in Brazil the Nikkei greatly improved agricultural methods and introduced the wider population to authentic Japanese and Nikkei cuisines in restaurants, which now outnumber both the Brazilian barbecue eateries known as churrascarias and even the pizzerias. Japanese street-food is also hugely popular in Brazil thanks to the Nikkei community who serve their own versions of deep-fried gyoza (pastis), yakisoba and takoyaki (fried octopus balls) to name just a few. In contrast, in Peru the Nikkei massively expanded the repertoire of Pacific fish used and improved the methods of preparation of popular national dishes, for example ceviche. They also introduced novel ways of preparing fish such as the tiradito sashimi-style raw fish served with a citrus leche de tigre sauce.

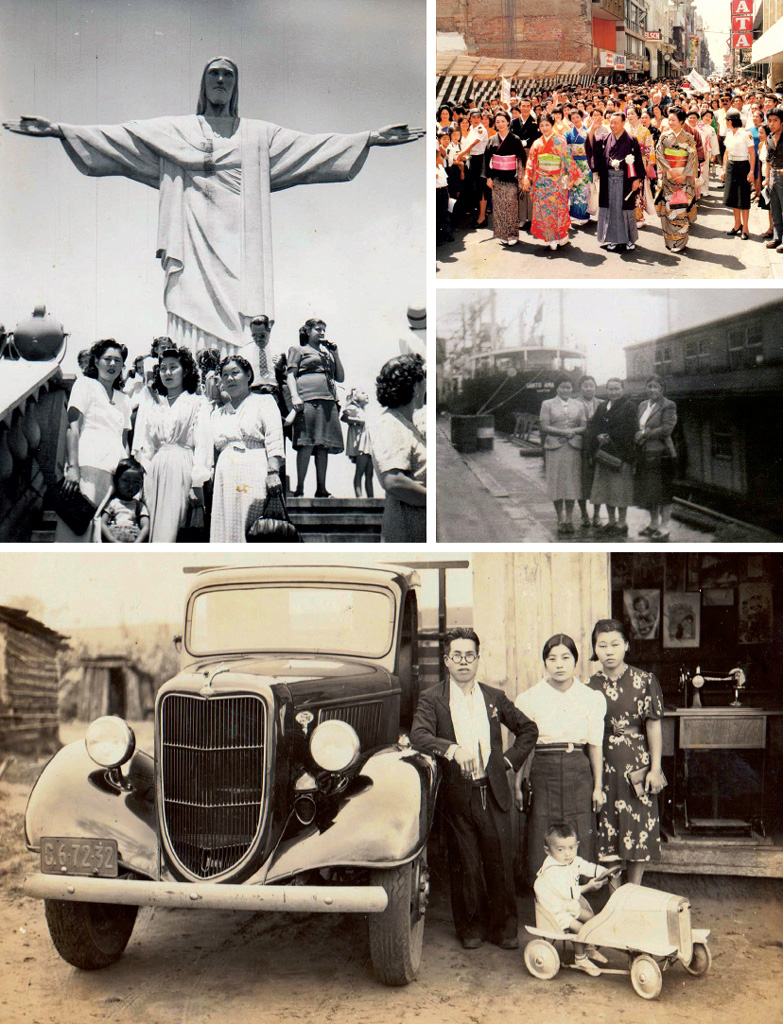

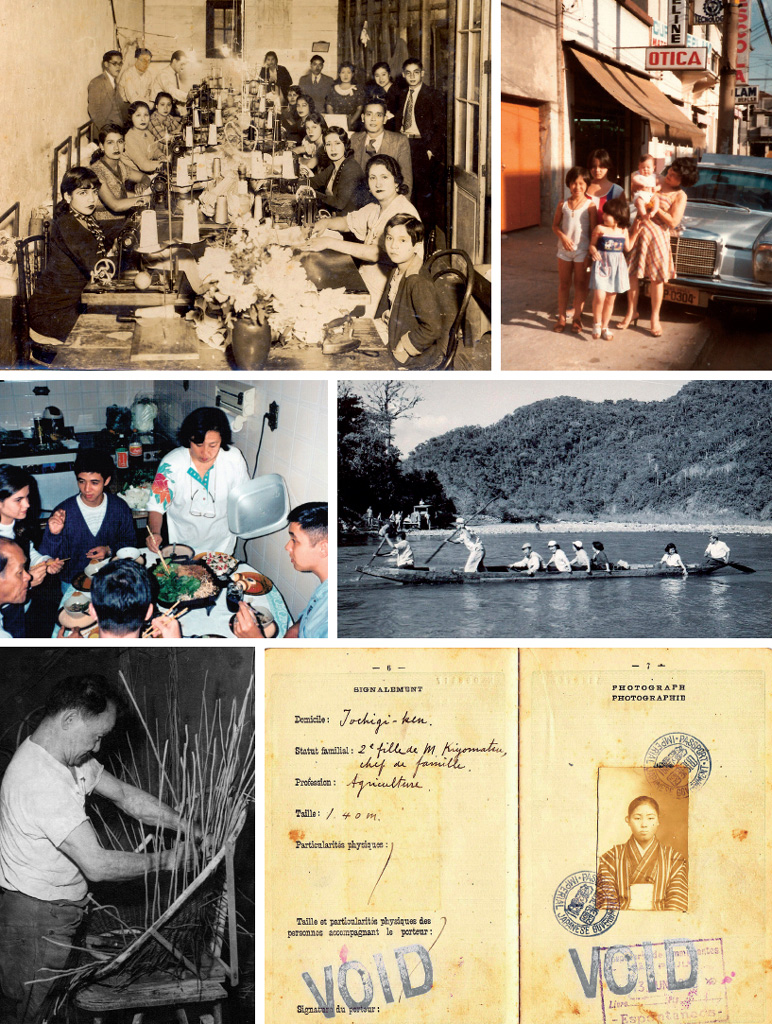

Japanese migration to South America a potted history

After 300 years of almost total isolation from the outside world, the Meiji Restoration in 1868 saw an opening up of Japan to migration both in and out of the country. This major modernisation of Japanese society not only ended the feudal system, which had been in place for hundreds of years, but also had some adverse effects on the economy particularly in rural areas. In addition, after the Sino-Japanese (189495) and Russo-Japanese (190405) wars, Japan had difficulty reabsorbing its returning soldiers and large numbers of Japanese citizens decided to search for a new life overseas. The government of Japan, in fact, entered into agreements with other nations, including Brazil and Peru, to encourage and support the emigration of its own nationals.

Japanese emigration began in the 1870s, and over the next 50 years around one million citizens emigrated. Major destinations were Brazil, Hawaii and Manchuria (taking around 25% each), with the rest heading all over the world 4% ending up in Peru. Most Japanese in Hawaii migrated there before it was annexed by the USA and from there many moved on to California. The emigrants were, on average, better educated than those who remained and many left home with dreams of riches in the Americas. In South America, the opportunities available were in farming for sugar in Peru, and coffee in Brazil. The first vessel, the Sakura Maru, arrived in Callao, Peru in 1899. Nine years later in Brazil, the first 781 Japanese men, women and children arrived in Santos aboard the Kasato Maru. This later influx was intended to solve the coffee farming manpower crisis caused by the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888. In Japan, campaigns advertising opportunities in Brazil promised great gains for all willing to work on coffee farms. The long trip from Japan to Brazil it took 52 days from Kobe to So Paolo was subsidised by the Brazilian government. These were powerfully attractive to Japanese workers seeking a better life outside of their home country. However, the newly arrived workers would soon discover harsher conditions than they had anticipated, akin to those endured by the newly liberated slaves. Even though Japanese immigrants had lived in frugal conditions in Japan, these could not compare to what awaited them in Brazil.

According to Tomoo Handas book The Japanese Immigrant a History of their Life in Brazil, by 1912 over 60% of Nikkei had left the farms to move to the cities in search of better living conditions and work in professions more similar to their own. Many settled in the So Paulo neighbourhood of Liberdade and set up what were later to become the many restaurants in this area. Most of the Japanese migrants to Peru and Brazil imagined their stay as temporary a way to achieve prosperity before returning home. However, the advent of the Second World War and the demise of Japan resulted in most of them considering South America as their permanent home.

My family a story of migration

My grandfather, Takeshi Hara, was officially an American, born to Japanese parents in Hawaii in 1907. He arrived in Brazil with his parents as a young child and embraced his adopted country as his own. He fell in love with the South American lifestyle, so much so that he ran off with a voluptuous Uruguayan woman, before his scandalised family sent him packing to a close-knit Japanese farming community in the interior of So Paulo state to mend his ways, and it was here that he met my Japanese grandmother Seki Suzuki. Born in 1912 in Fukuoka on the Japanese island of Kyushu, she was brought to Brazil in 1927 when she was 15 by an aunt who was migrating with her whole family and needed to make up numbers for the departure of their ship. She was promised that she would soon be returned to her family in Japan, but my grandfather and love got the better of her and so Brazil became her new home.

After losing their coffee farm to severe frost, my grandparents migrated to the city of So Paulo and set up a fruit and vegetable shop with their family including my father, Yasuo Hara. One of seven children, my dad was a natural entrepreneur he soon realised that fruit and veg would not earn him the money he dreamed of. So, he bought a VW Beetle, learned how to drive it and started off on his first career as a travelling salesman, buying and selling watches across southern Brazil. It was during this phase of his life that he met my mother Ana-Maria Saladini in the state of Paran. They returned to the city of So Paulo where they settled down, opening a watch and jewellery shop, and starting a family my sisters Jacqueline and Patricia, myself and then my brother Ricardo.