Contents

Dedication

To anyone whos ever been stung, bitten, irritated, disgusted, annoyed, driven mad, or terrified by common insects and household pests Mother Nature has the natural and safe solution.

May you be bugged, boggled, and pestered no more!

Acknowledgments

I give thanks to God above for the herbs and to the plant spirits themselves for imparting their knowledge; to my grandfather, Earl C. Ashe, for introducing me to folk herbalism as a young girl; to my friends and family for their feedback on my formulations; and to Deborah Balmuth, my chief editor at Storey Publishing, for believing in me once again and allowing me to share my herbal wisdom for the benefit of my health-seeking readers.

Introduction

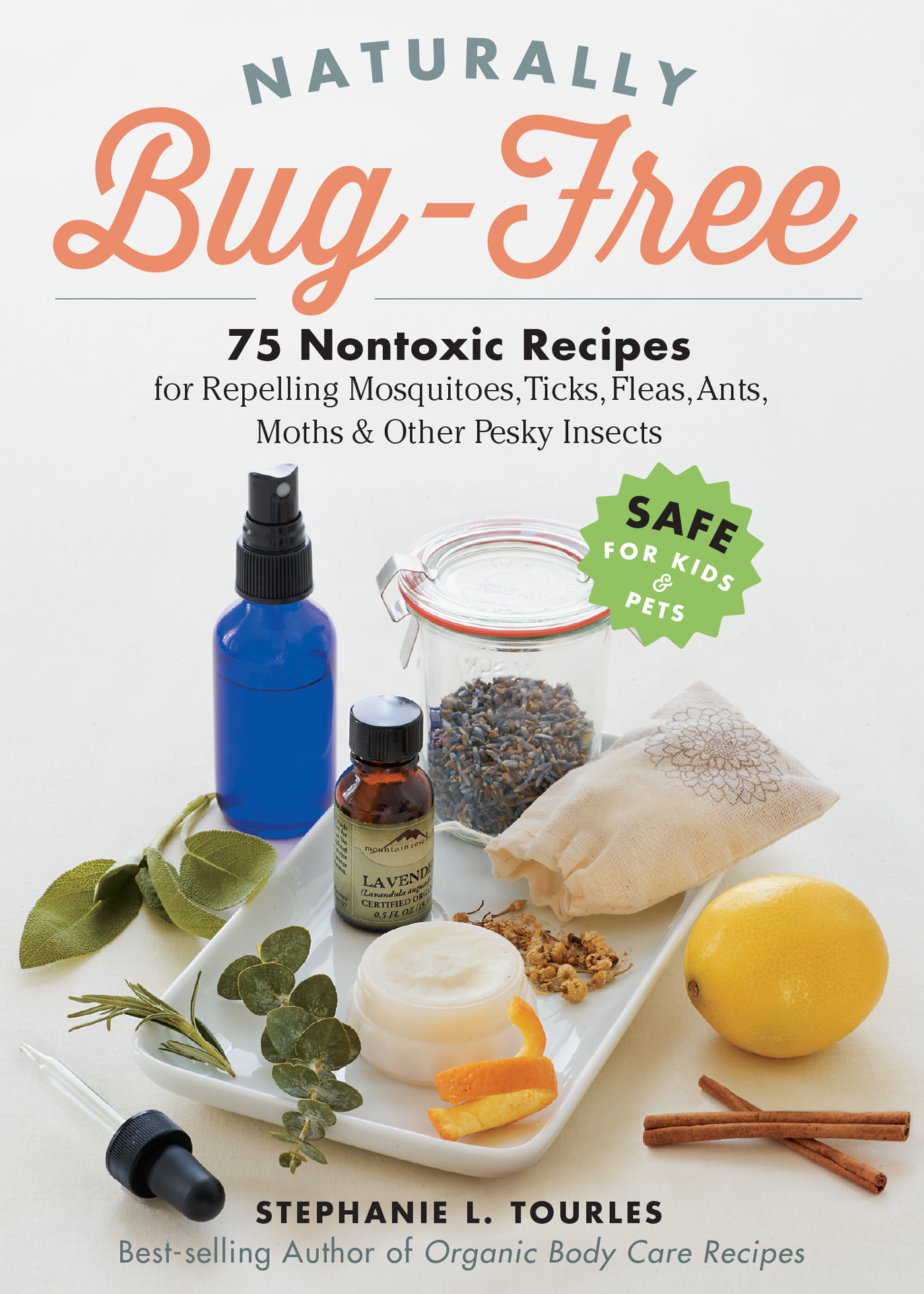

We all hate those annoying pests that plague us on picnics, pounce on our pets, and parade through our pantries. We battle them inside and out: mosquitoes, fleas, ticks, biting flies, clothes and pantry moths, flour and grain beetles and mites, stinkbugs, ants, cockroaches, spiders, silverfish, earwigs, gnats, houseflies, fruit flies, centipedes, pill bugs, and so many other crawling, flying creatures.

I hear all the time from people looking for alternatives to the standard chemical arsenal that is available to repel or control insects and pests. Ive made my own herb-based repellent products for years. They smell pleasant and work quite well, though I admit that when deerflies and blackflies (the latter are jokingly referred to where I live as the Maine State Bird) are particularly voracious, I don protective clothing or stay indoors.

My cats, too, no longer suffer skin and respiratory irritation from flea-and-tick powders and those liquid spot-on products. Ive perfected herbal formulations that keep them comfortable and healthy and, as a bonus, smelling fresh and clean. And I use herbs and other natural ingredients to keep my quaint country home, built in 1800, free of bugs and mice.

Many herbs emit powerfully aromatic volatile oils that, while appealing to most humans, repel many bugs and rodents, whose sense of smell is far more acute than ours. Certain herbs, such as tansy, wormwood, and pennyroyal, and other natural ingredients, such as pure borax and diatomaceous earth, act as insecticides rather than mere repellents; when used properly, however, they are harmless to people, animals, and the environment.

The Problem with Modern Insecticides

If you look at chemical insecticides purely from the standpoint of their intended benefit, they should be considered a scientific success, being tremendously effective against insects that transmit disease and damage crops and property. But thats where the success stops. Chemical insecticides, even when properly applied (not to mention when used carelessly or excessively), also kill beneficial insects, birds, and small mammals. Eventually many species of insects become resistant or immune. In addition, some insecticides, notably DDT, tend to persist in the environment, eventually accumulating in the body tissues of wildlife, fish, and humans.

Three of the most common, broad-spectrum insecticides used in the United States today are outlined below. All are neurotoxins that disrupt nerve impulses, then kill or disable insects in short order. Altogether, they are registered for use on over 100 different crops, animals, ornamental plants, and indoor areas.

The organophosphates (OPs), which include chlorpyrifos, diazinon, malathion, and parathion, among others, are a family of household and agricultural insecticides. Many that have been in use for decades are at the top of the Environmental Protection Agencys hazardous chemical list. OPs are also used in military settings and by terrorists as chemical warfare nerve agents and have a cumulative effect, meaning that multiple exposures amplify the toxicity. Of all pesticides, these are the most toxic to vertebrates.

Carbamate insecticides, which include carbaryl (marketed as Sevin), are similar to organophosphates, but they break down more quickly. One EPA report describes them this way: very broad spectrum toxicity and highly toxic to fish, bees, and parasitic wasps.

Pyrethroids, supposedly the least toxic and least persistent of the three types, are frequently used in household insecticides, on many food crops, on ornamental plants and lawns, and in veterinary products. Permethrin, a type of pyrethroid, is the most common active ingredient in indoor/outdoor insect sprays and has been classified by the EPA as likely to be carcinogenic to humans. It is used in indoor fogging systems, and in city and suburban mosquito misting systems. Pyrethroids are extremely toxic to fish, as well as bees and other beneficial insects.

DEET: The Best Defense?

Developed in the 1940s by the U.S. Army for protection of military personnel in insect-infested areas and registered in the U.S. for use by the general public in the mid-1950s, N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) is one of the most widely used ingredients in store-bought, conventional bug sprays for personal use. It is a colorless, oily liquid with a mild odor and is designed to repel, rather than kill, insects, including mosquitoes, biting flies, fleas, ticks, and other small insects.

DEET is used by an estimated one-third of the U.S. population each year. Its use has increased dramatically since the 1970s as an aid to protect against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and other tick-borne illnesses, as well as West Nile virus. Although it clearly works as intended, it is not safe even the EPA, as well as the product package label, says that you should wash it off your skin when you return indoors, avoid breathing it in, and not spray it directly on your face. A known eye irritant, it can cause rashes, soreness, or blistering.

A mosquito repellent containing 25 percent DEET cannot be applied on or near plastic, leather, synthetic fabrics, watch crystals, or painted or varnished surfaces, including automobiles. If this chemical, which in addition to being toxic to insects is also toxic to birds and aquatic life, can damage plastic, leather, and glass, then what is it doing to you? Remember that your skin is your largest organ, and it can absorb up to 60 percent of what you put on it!

Side Effects of Insecticides

All chemical insecticides, whether applied in vapor, liquid, or powder form, have potentially toxic side effects if the vapors are inhaled, the product is orally consumed (for example, by a pet licking its fur), or through dermal exposure. Side effects can include nausea, headache, irritability, skin irritation, tremors, weakness, blurry vision, convulsions, vomiting, abdominal cramps, twitching, confusion, and/or difficulty breathing. Chronic exposure may lead to disorientation, speech difficulties, sleep disturbances, eye pain, and/or behavioral disorders. Each year, millions of people report suffering medically significant side effects from the use of insecticides.

When chemical-based insecticides are sprayed in the home, the vapors evaporate and can recondense on furniture, bedding, and objects such as toys. Young children, who spend a lot of time putting things in their mouths, are far more vulnerable than adults to such exposure.