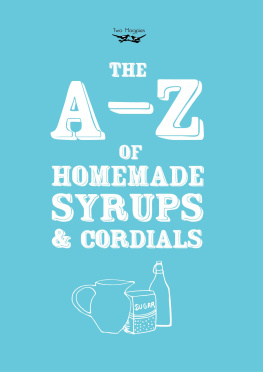

Copyright 2013 Two Magpies Publishing

An imprint of Read Publishing Ltd

Home Farm, 44 Evesham Road, Cookhill, Alcester, Warwickshire, B49 5LJ

Commissioning Editor Rose Hewlett

Words by Amelia Carruthers

Design and Illustrations by Zo Horn Haywood

This book is copyright and may not be reproduced or copied in any way without the express permission of the publisher in writing.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Commissioning Editor Rose Hewlett

Words by Amelia Carruthers

Design and Illustrations by Zo Horn Haywood

Contents

Introduction

Welcome to the wonderful world of jellies and jams.

As well as lots of classic recipes, this book is filled with tips and techniques on making the perfect preserve. Whats more, you dont even need lots of equipment or a vast array of ingredients to get started. Making your own jams and jellies at home is very often cheaper than buying them - perfect for the thrifty home-chef. The cost of ingredients is low (especially if you pick them yourself), and by creating large batches, you can save a huge amount of money.

Preserving fruit by turning it into jam, for example, involves boiling (to reduce the fruits moisture content and to kill bacteria, yeasts, etc.), sugaring (to prevent their re-growth) and sealing within an airtight jar (to prevent recontamination). Thats it! Jellies are largely similar, but generally involve the addition of gelatine and straining to produce a clear end result. Such methods of preservation with the use of either honey or sugar was well known to the earliest cultures, and in ancient Greece, fruits kept in honey were common fare. Quince, mixed with honey, semi-dried and then packed tightly into jars was a particular speciality. This method was taken, and improved upon by the Romans, who cooked the quince and honey (similar to our modern jams)- producing a solidified texture which kept for much longer.

These techniques have remained popular into the modern age, especially so during the high-tide of imperialism, when trading between Europe, India and the Orient was at its peak. This fervour for trade had two fold consequences; the need to preserve a variety of goods, and the arrival of sugar cane in Europe. Preserving fruits through jams and jellies became especially popular in Northern European countries, where there was not enough natural sunlight to dry food outdoors. Jellies were a mainstay of the upper-class Victorian table, more used for decoration and display (some moulds were incredibly elaborate - almost pieces of art) than food preservation proper. Made in ceramic moulds, cut jelly shapes were suspended in clear jellies, and multi-part moulds allowed for centres with contrasting colours and flavours. Austerity in the war years soon put a stop to such complex production, but for the common people though, Jellies were most frequently used for savoury items. Some foods such as eels, naturally form a protein gel when cooked - and this dish became especially popular in the East End of London, where they were (and are) eaten with mashed potatoes. Not to worry though, in this A-Z of Jams and Jellies well be sticking strictly to fruits and flowers!

The wonderful thing about making your own homemade products is the fun one can have with creating customised labels and garnishes to the finished jars (think berries, citrus zest, herb sprigs) a perfect present as well as personal treat. We hope that the reader is inspired by this book to start making their own jams and jellies, a delicious and rewarding pastime.

Amelia Carruthers

General Preliminaries

Always ensure the fruits that you use in your jam or jelly recipes have been washed thoroughly, especially if they have been gathered from low hedgerows, or bushes that are near roads. If the fruits have pips or cores, you may wish to remove these before cooking, as some may leave a bitter taste to the final product. Some however, such as apples pips, cores and peel contain vital pectin which will ensure your jam or jelly reaches a proper consistency. This does differ, so make sure to read each recipe carefully.

The recipes in this book will use either 500g or 1kg of fruit (if this is the main ingredient), which should produce between three and six traditional jam jars, or the equivalent of jelly. The amount of jam or jelly you produce will depend on how strong you wish the end result to be though. Some people prefer much thicker, viscous jams, whilst others will only be looking for a lightly flavoured jelly. Other ingredients such as lavender, rose or ginger will require much less primary ingredient though, as their natural flavours are so strong. Have fun experimenting and just use what youve got!

Within this A-Z, you will find information on how to select your jam jars - as well as how to sterilise and seal them properly. You will also find essential tips on temperature (how to check a jam or jellies setting point), what equipment and utensils you will need, and how to select the best and freshest ingredients for your homemade treats. Good luck, and happy cooking.

A is for... Apples

Traditional folklore is brimming with references to the apple trees virtues. This ancient, and thoroughly English tree has provided abundant food for centuries, and has many uses in the kitchen (both sweet and savoury) as well as herbal remedies. The crab apple (Pyrus Malus) is native to Britain, and is the wild ancestor of all our modern-day cultivated varieties. Today, most wild English varieties of crab apples are red in colour, meaning that your resultant jelly will have a beautiful, pale red sheen - not to mention plenty of flavour! Crab apples are ready for picking in late autumn, so this dish will make a perfect accompaniment to those warming-winter-roasts. Also, try this jelly as a glaze with smoked and cured meats as well as a wonderful addition to traditional gravy, giving a hint of fruit sweetness to your dishes.

Crab Apple Jelly

Ingredients

1 kg Crab Apples

250g Caster Sugar

1 Lemon

Method

- Wash your apples and remove any bruised fruit (leaving this in would adversely affect the quality of the finished jelly).

- Place the apples with enough water to cover in a saucepan.

- Bring to the boil and cook until the fruit is soft (this should take roughly thirty minutes).

- Pour the pulp into a jelly bag (over another saucepan) and let it strain overnight. Remember not to squeeze the bag, or this will make your jelly cloudy.

- The next day, add the sugar in the ratio of ten parts juice, to seven of sugar. Also, add a good squeeze of lemon juice.

- Bring to the boil, and stir to dissolve the sugar.

- Keep at a rolling boil for roughly forty minutes, making sure to skim off any scum which rises to the surface.

- Test the setting point (see the section on T emperature) if your jelly is set, take it off the heat, if not, carry on cooking.

- Pour your jelly into warm, sterilised jars and tightly seal. Voila!