Charles River Editors provides superior editing and original writing services across the digital publishing industry, with the expertise to create digital content for publishers across a vast range of subject matter. In addition to providing original digital content for third party publishers, we also republish civilizations greatest literary works, bringing them to new generations of readers via ebooks.

Sign up here to receive updates about free books as we publish them , and visit Our Kindle Author Page to browse todays free promotions and our most recently published Kindle titles.

Introduction

A picture of the Prophets Rock near the battlefield

The Battle of Tippecanoe (November 7, 1811)

The Battle of Tippecanoe, fought on November 7, 1811 near present-day Lafayette, Indiana, involved forces of fewer than 2,000 Native American warriors and white soldiers, and only about 300 men were killed or wounded on both sides. Given those numbers, its apparent that the battle was far from being a Saratoga or a Gettysburg in terms of its scale or significance as an historical turning point, yet it was one of the most important battles in shaping American history during the early 19 th century. The battle also involved an epic confrontation between two important American figures: William Henry Harrison, who would become the 9 th president of the United States by running on his success in the battle, and the Shawnee war chief Tecumseh, arguably the most famous Native American leader in American history.

From the American Revolution up through the Battle of Tippecanoe, Native Americans in the Old Northwest (todays Midwestern states) had been putting up stout resistance to that regions settlement by white land speculators and settlers. Things came to a head when Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet Tenskwatawa, spearheaded a movement in the region that greatly influenced the areas Native Americans. In 1806, Harrison began to publicly denounce Tenskwatawa to other tribal leaders, calling him a fraud and charlatan, but the Shawnee Prophet responded by accurately predicting a solar eclipse, which embarrassed Governor Harrison, and after this event, which tribal leaders took as a sign of Tenskwatawas authenticity, his movement grew even more rapidly. By 1808, Tenskwatawa and his followers had moved west and founded a large, multi-tribal settlement near the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash Rivers, called Prophetstown or Tippecanoe. Assisted by his brother Tecumseh, Tenskwatawas settlement grew tremendously and eventually became the largest Native American settlement in the region. It also served as a Native American cultural center and provided a steady cadre of warriors ready to hear the Prophets message that they should return to their ancestral lifestyles and force the white settlers and their culture out of their territory.

By November 6, 1811, Harrison and his men were encamped near the Native American settlement. Only the narrow southern point of Harrisons perimeter and the northeastern side, southwest of a Catholic Mission, posed serious threats of attack. Sentinels were posted that night, and the Yellow Jackets, led by Captain Spier Spencer, manned the southern point of the perimeter.

Although accounts of the battle conflict, all agree that sentinels aroused the main body of the American troops when they detected Native American warriors attacking the Americans perimeter from the south. The initial Native American attack struck the southern point of the defensive perimeter around 4:30 a.m. on November 7, 1811, and almost immediately the warriors rushed in among the American defenders manning that sector. Soldiers defending the southern side of the perimeter suffered the highest casualties, with the Yellow Jackets suffering a 30% casualty rate, but in fighting lasting about two hours Harrisons force of roughly 1,000, suffered only 62 dead and about 120 wounded. As the sun rose, the warriors began running low on ammunition, and the light revealed their small numbers, leading them to break off the attack and retreat towards Prophetstown.

Anticipating the imminent return of Tecumseh and Native American reinforcements, Harrison had his troops working to reinforce the perimeter for the remainder of the day. A small reconnaissance party was dispatched to the town the following morning and found it virtually deserted. Everything of value was confiscated, including 5,000 bushels of corn and beans, and the town was burned. Harrison and his troops loaded the wounded onto wagons and departed the area for Fort Harrison on the day after the battle (November 8), and on November 9, 1811, most of the militia was released from service (though over 200 regulars would remain in the area for some time).

The battle was hardly a decisive victory, but at the end of the fighting the Americans still held their perimeter, allowing them to claim victory. While Tippecanoe was clearly not a total victory, and Native American resistance would continue through the War of 1812, the battle is widely considered the end of Tecumsehs War and did help bring about the decline of Native American ascendance in the region.

This book analyzes the background that led up to the battle and its aftermath. Along with pictures of important people, places, and events, you will learn about the Battle of Tippecanoe like never before, in no time at all.

The Battle of New Orleans (January 1815)

There are countless examples of battles that take place in wars after a peace treaty is signed. The last battle of the Civil War was a skirmish in Texas that Confederate forces won, nearly a month after Lees surrender at Appomattox. But its certainly rare for the most famous battle of a war to take place after the peace treaty is signed.

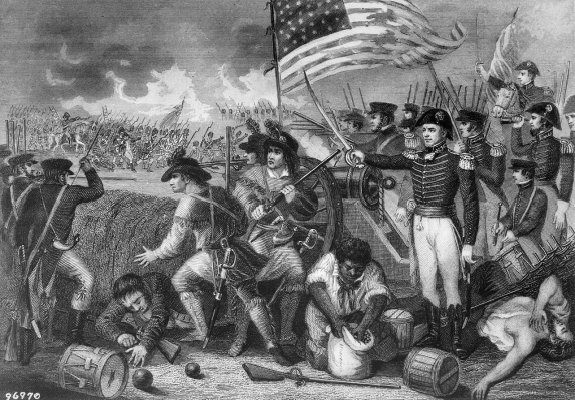

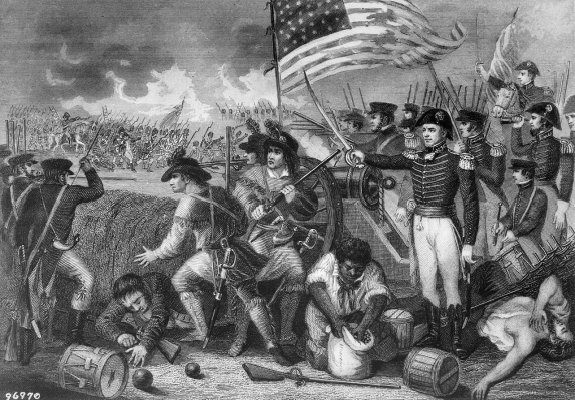

Luckily for Andrew Jackson, the War of 1812 was that unique exception. Less than a year after his victory in the Battle of Horseshoe Creek, Jackson led his forces into a more important battle at the Battle of New Orleans. The British hoped to grab as much of the land on the western frontier as they could, especially New Orleans, which had a prominent position on the Mississippi River for trading. With more than 8,000 soldiers aboard a British fleet sailing in from Jamaica in early January 1815, the attack on New Orleans promised to be a significant one, while Jacksons men defended New Orleans with about half that number. This went on despite the fact that the two sides had signed the Treaty of Ghent on Christmas Eve 1814, which was supposed to end the war. However, the slow nature of bringing news from England to America ensured that the battle would take place anyway.

At the beginning of the battle, Jackson and his forces were aided by the weather, with the first fighting taking place in heavy fog. When the fog lifted as morning began, the British found themselves exposed to American artillery. On top of that, Jacksons men held out under an intense artillery bombardment and two frontal assaults on different wings of the battle, before Jackson led a counterattack. By the end of the battle, the Americans had scored a stunning victory. Jacksons men killed nearly 300 British, including their Major General Pakenham and his two lead subordinates. More importantly, nearly 1500 additional British were captured or injured, and the Americans suffered fewer than 500 casualties.