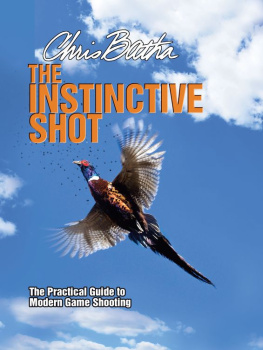

SHOOTING

FOR SPORT

A GUIDE TO DRIVEN GAME SHOOTING,

WILDFOWLING AND THE DIY SHOOT

TONY JACKSON

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

Tony Jackson 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 934 6

Contents

Introduction

The basic principle of the shotgun has remained unaltered since the very first handgonne was held, doubtless with some trepidation, by a fourteenth-century soldier who, from the primitive character of the weapon in use, tended to expose himself to rather more danger than the enemy he somewhat optimistically hoped to slay. In those early days hand cannon, in various guises, were largely employed as weapons of war to fire a ball or bullets, and as one might anticipate, these weapons were highly inaccurate. They were, however, calculated to cause dismay amongst an enemy still armed with longbows and crossbows. It was not until the invention of the wheel-lock that guns were used for sporting purposes, and then it was largely on the Continent, for whilst firearms were being used for sport in the fifteenth century in Germany, Spain, Italy, and to some extent in France, it was not until the latter part of the seventeenth century that firearms were employed in Britain for the chase, and then they were mostly of foreign manufacture.

The development of the sporting firearm over the centuries has been related many times. Nevertheless, despite the many variations on a theme, the principle remained the same, namely a projectile to be fired at the quarry, though it was not until the use of hayle shot, or lead pellets, that sporting shooting as we know it today really took off. Two hundred or so pellets, though they might be driven by slow-burning, coarse black powder along the length of a crudely drawn and finished barrel, could still perform remarkable execution when fired at duck, geese or other birds resting on the ground or water or feeding in flocks.

In those early days it was soon appreciated that whilst barrels could be made to ever finer, carefully regulated specifications, igniting the charge was the main problem. The sportsman wandering about with a matchlock, consisting of a loaded gun to be ignited and discharged by a slow-burning fuse, was at a distinct disadvantage as it would have been virtually impossible to stalk deer or other quarry with a glowing match, not to mention the time lag involved in actual ignition. It was not until the invention of rifling in the fifteenth century at Nuremburg, in conjunction with the wheel-lock, that sporting shooting really took off.

The principle of the wheel-lock was simple. A spring revolved against a flint to produce a shower of sparks which ignited fine black powder in a pan, and this in turn activated the main charge in the breech. This early sixteenth-century principle, now established, was refined into the flintlock system: this simply involved a shaped flint held in hammer jaws which, when released against spring pressure by the trigger, struck a steel plate to create a shower of sparks.

The principle remained in use through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and it was only the experiments of an obscure Scottish minister, the Rev. Alexander John Forsyth that resulted in the practical application of the percussion muzzle-loading gun in 1805. The Forsyth lock system involved the use of fulminate of mercury as a detonating agent, and the advantages were at once apparent: it was faster in use than the flintlock system, and eliminated the requirement for fine powder in the pan. From this modest beginning was to develop the percussion cap, which was employed by the muzzle-loader until the invention by the French of the breech-loading system in 1851: this system completely transformed the use of firearms in all their guises.

The development of the shotgun in the nineteenth century was to result in a series of dramatic changes in the shooting field. In the eighteenth century, game, notably partridges, was walked up, because the concept of the driven shoot, or battue, had not yet crossed the Channel. Pheasants were still relatively scarce, and only the grey partridge, and in parts of East Anglia the French or red-legged partridge, were relatively common. The sportsman, armed with a muzzle-loading flintlock and draped with powder and shot flasks, with a servant to carry the bag and accompanied by a brace of pointers or spaniels, would spend his days walking the long-stemmed stubble fields in search of coveys. There was a leisured calm about the day as the sportsman, perhaps with one or two like-minded companions, wandered the peaceful countryside, pausing between each shot, as blue-grey smoke rolled away, to reload his long-barrelled flintlock. Not every shot was guaranteed, for there might be the occasional misfire due to a flash in the pan.

Drastic change is always painful, and even the redoubtable Colonel Peter Hawker, the father of wildfowling, was initially reluctant to acknowledge that the percussion or detonating system had made the flintlock redundant. Eventually, however, he was forced to concede that for neat shooting in the field, or covert, and also for killing single shots at wild-fowl rapidly flying, and particularly at night... its trifle inferiority to the flint is tenfold repaid by the wonderful accuracy it gives in so readily obeying the eye.

That the pheasant was still relatively scarce on the ground is shown by the fact that Hawkers bag in a season might be no more than half-a-dozen birds, and that he would muster a small army of men to scour the countryside on hearing the report of a vagrant wandering pheasant. On the Continent, however, vast bags of game, small and large, had long been the fashion since the seventeenth century. In 1753, for instance, during the space of twenty days shooting in Bohemia, some twenty-three Guns killed a total of 47,317 head of game, consisting of 19,545 partridges, 18,273 hares and 9,499 pheasants. One might have supposed that by the end of this three-week slaughter the participants would have been sickened, deafened and bored beyond measure.

The Driven Shoot

The battue, or driven shoot, when it did arrive on these shores in the early nineteenth century, was by no means received with open arms. An older generation of sportsmen regarded this form of sport as both degenerate and symptomatic of an effeminate age when men could no longer pursue game on foot, but instead stood to have it driven towards them. R. S. Surtees, writing in the 1850s, is bitter in his satire when, writing in Plain or Ringlets, he condemns the battue as not being the thing for able-bodied men; and the fact of their being of foreign extraction does not commend them to our notice. Nevertheless, whether it was approved of or not, driven shooting was here to stay, and with the invention of the breech-loader, the new mode of shooting quickly became established: now the sportsman could swiftly reload, initially using pin-fire cartridges until these were replaced by central- fire cartridges.

Next page