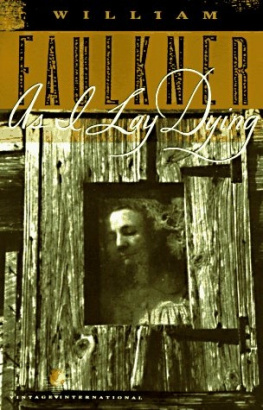

AS I LAY DYING

TO

Hal Smith

Copyright 1930, and renewed 1957, by WilliamFaulkner

All rights reserved under International andPan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of CanadaLimited. Toronto.This edition was published by Random House, Inc., in

1964.

The corrections in this edition are based on acollation, under the direction of James B. Meriwether, of th< first editionand Faulkner's original manuscript and typescript.

Library of Congress Cataloging in PublicationData

Faulkner, William, 1897-1962.

As I lay dying.

I. Title.

[PZ3.F272Asll] [PS3511.A86] 813'i'2 72-8023 ISBN0-394-70254-9

Manufactured in the United States of America VintageBooks Edition, February 1964

AS I LAY DYING

Darl

Jewel and I come up from the field, following thepath in single file. Although I am fifteen feet ahead of him, anyone watchingus from the cottonhouse can see Jewel's frayed and broken straw hat a full headabove my own.

The path runs straight as a plumb-line, wornsmooth by feet and baked brick-hard by July, between the green rows of laid-bycotton, to the cottonhouse in the center of the field, where it turns andcircles the cottonhouse at four soft right angles and goes on across the fieldagain, worn so by feet in fading precision.

The cottonhouse is of rough logs, from betweenwhich the chinking has long fallen. Square, with a broken roof set at a singlepitch, it leans in empty and shimmering dilapidation in the sunlight, a singlebroad window in two opposite walls giving onto the approaches of the path. Whenwe reach it I turn and follow the path which circles the house. Jewel, fifteenfeet behind me, looking straight ahead, steps in a single stride through thewindow. Still staring straight ahead, his pale eyes like wood set into hiswooden face, he crosses the floor in four strides with the rigid gravity of acigar store Indian dressed in patched overalls and endued with life from thehips down, and steps in a single stride through the opposite window and intothe path again just as I come around the corner. In single file and five feetapart and Jewel now in front, we go on up the path toward the foot of thebluff.

Tull's wagon stands beside the spring, hitched tothe rail, the reins wrapped about the seat stanchion. In the wagon bed are twochairs. Jewel stops at the spring and takes the gourd from the willow branchand drinks. I pass him and mount the path, beginning to hear Cash's saw.

When I reach the top he has quit sawing. Standingin a litter of chips, he is fitting two of the boards together. Between theshadow spaces they are yellow as gold, like soft gold, bearing on their flanksin smooth undulations the marks of the adze blade: a good carpenter, Cash is.He holds the two planks on the trestle, fitted along the edges in a quarter ofthe finished box. He kneels and squints along the edge of them, then he lowersthem and takes up the adze. A good carpenter. Addie Bundren could not want abetter one, better box to lie in. It will give her confidence and comfort. I goon to the house, followed by the

Chuck. Chuck. Chuck.

of the adze.

Cora

So I saved out the eggs and baked yesterday. Thecakes turned out right well. We depend a lot on our chickens. They are goodlayers, what few we have left after the possums and such. Snakes too, in thesummer. A snake will break up a hen-house quicker than anything. So after theywere going to cost so much more than Mr Tull thought, and after I promised thatthe difference in the number of eggs would make it up, I had to be more carefulthan ever because it was on my final say-so we took them. We could have stockedcheaper chickens, but I gave my promise as Miss Lawington said when she advisedme to get a good breed, because Mr Tull himself admits that a good breed ofcows or hogs pays in the long run. So when we lost so many of them we couldn'tafford to use the eggs ourselves, because I could not have had Mr Tull chide mewhen it was on my say-so we took them. So when Miss Lawington told me about thecakes I thought that I could bake them and earn enough, at one time to increasethe net value of the flock the equivalent of two head. And that by saving theeggs out one at a time, even the eggs wouldn't be costing anything. And thatweek they laid so well that I not only saved out enough eggs above what we hadengaged to sell, to bake the cakes with, I had saved enough so that the flourand the sugar and the stove wood would not be costing anything. So I bakedyesterday, more careful than ever I baked in my life, and the cakes turned outright well. But when we got to town this morning Miss Lawington told me thelady had changed her mind and was not going to have the party after all.

"She ought to taken those cakesanyway," Kate says.

"Well," I say, "I reckon she neverhad no use for them now."

"She ought to taken them," Kate says."But those rich town ladies can change their minds. Poor folks cant."

Riches is nothing in the face of the Lord, for Hecan see into the heart. "Maybe I can sell them at the bazaarSaturday," I say. They turned out real well.

"You cant get two dollars a piece forthem," Kate says.

"Well, it isn't like they cost meanything," I say. I saved them out and swapped a dozen of them for thesugar and flour. It isn't like the cakes cost me anything, as Mr Tull himselfrealises that the eggs I saved were over and beyond what we had engaged tosell, so it was like we had found the eggs or they had been given to us.

"She ought to taken those cakes when shesame as gave you her word," Kate says. The Lord can see into the heart. Ifit is His will that some folks has different ideas of honesty from other folks,it is not my place to question His decree.

"I reckon she never had any use forthem," I say. They turned out real well, too.

The quilt is drawn up to her chin, hot as it is,with only her two hands and her face outside. She is propped on the pillow,with her head raised so she can see out the window, and we can hear him everytime he takes up the adze or the saw. If we were deaf we could almost watch herface and hear him, see him. Her face is wasted away so that the bones draw justunder the skin in white lines. Her eyes are like two candles when you watchthem gutter down into the sockets of iron candle-sticks. But the eternal andthe everlasting salvation and grace is not upon her.

"They turned out real nice," I say."But not like the cakes Addie used to bake." You can see that girl'swashing and ironing in the pillow-slip, if ironed it ever was. Maybe it willreveal her blindness to her, laying there at the mercy and the ministration offour men and a tom-boy girl. "There's not a woman in this section couldever bake with Addie Bundren," I say. "First thing we know she'll beup and baking again, and then we wont have any sale for ours at all."Under the quilt she makes no more of a hump than a rail would, and the only wayyou can tell she is breathing is by the sound of the mattress shucks. Even thehair, at her cheek does not move, even with that girl standing right over her,fanning her with the fan. While we watch she swaps the fan to the other handwithout Stopping it.

"Is she sleeping?" Kate whispers.

"She's just watching Cash yonder," thegirl says. We can hear the saw in the board. It sounds like snoring. Eula turnson the trunk and looks out the window. Her necklace looks real nice with herred hat. You wouldn't think it only cost twenty-five cents.

"She ought to taken those cakes," Katesays.

I could have used the money real well. But it'snot like they cost me anything except the baking. I can tell him that anybodyis likely to make a miscue, but it's not all of them that can get out of itwithout loss, I can tell him. It's not everybody can eat their mistakes, I cantell him.

Next page