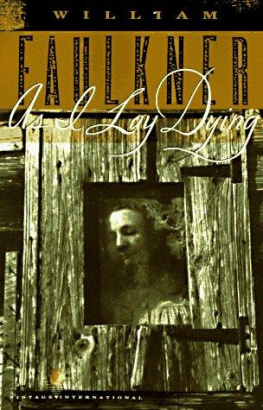

AS I LAY DYING

William Faulkner

TO

Hal Smith

Darl

Jewel and I come up from the field, following the path in singlefile. Although I am fifteen feet ahead of him, anyone watching us from thecottonhouse can see Jewel's frayed and broken straw hat a full head above myown.

The path runs straight as a plumb-line,worn smooth by feet and baked brick-hard by July, between the green rows oflaid-by cotton, to the cottonhouse in the center of the field, where it turnsand circles the cottonhouse at four soft right angles and goes on across thefield again, worn so by feet in fading precision.

The cottonhouse is of rough logs, frombetween which the chinking has long fallen. Square, with a broken roof set at asingle pitch, it leans in empty and shimmering dilapidation in the sunlight, asingle broad window in two opposite walls giving onto the approaches of thepath. When we reach it I turn and follow the path which circles the house.Jewel, fifteen feet behind me, looking straight ahead, steps in a single stridethrough the window. Still staring straight ahead, his pale eyes like wood setinto his wooden face, he crosses the floor in four strides with the rigid gravity of a cigar store Indian dressed in patched overallsand endued with life from the hips down, and steps in a single stride throughthe opposite window and into the path again just as I come around the corner.In single file and five feet apart and Jewel now in front, we go on up the pathtoward the foot of the bluff.

Tull's wagon stands beside the spring,hitched to the rail, the reins wrapped about the seat stanchion. In the wagonbed are two chairs. Jewel stops at the spring and takes the gourd from thewillow branch and drinks. I pass him and mount the path, beginning to hearCash's saw.

When I reach the top he has quit sawing.Standing in a litter of chips, he is fitting two of the boards together.Between the shadow spaces they are yellow as gold,like soft gold, bearing on their flanks in smooth undulations the marks of theadze blade: a good carpenter, Cash is. He holds the two planks on the trestle,fitted along the edges in a quarter of the finished box. He kneels and squintsalong the edge of them, then he lowers them and takesup the adze. A good carpenter. Addie Bundren could notwant a better one, better box to lie in. It will give her confidence andcomfort. I go on to the house, followed by the

Chuck. Chuck. Chuck.

of the adze.

Cora

So I saved out the eggs and baked yesterday. The cakes turned outright well. We depend a lot on our chickens. They are good layers, what few wehave left after the possums and such. Snakes too, in thesummer. A snake will break up a hen-house quicker than anything. Soafter they were going to cost so much more than Mr Tull thought, and after Ipromised that the difference in the number of eggs would make it up, I had tobe more careful than ever because it was on my final say-so we took them. Wecould have stocked cheaper chickens, but I gave my promise as Miss Lawingtonsaid when she advised me to get a good breed, because Mr Tull himself admitsthat a good breed of cows or hogs pays in the long run. So when we lost so manyof them we couldn't afford to use the eggs ourselves, because I could not havehad Mr Tull chide me when it was on my say-so we took them. So when MissLawington told me about the cakes I thought that I could bake them and earnenough, at one time to increase the net value of the flock the equivalent oftwo head. And that by saving the eggs out one at a time, even the eggs wouldn'tbe costing anything. And that week they laid so well that I not only saved outenough eggs above what we had engaged to sell, to bake the cakes with, I hadsaved enough so that the flour and the sugar and the stove wood would not becosting anything. So I baked yesterday, more careful thanever I baked in my life, and the cakes turned out right well. But whenwe got to town this morning Miss Lawington told me the lady had changed hermind and was not going to have the party after all.

"She ought to taken those cakes anyway," Kate says.

"Well," I say, "I reckonshe never had no use for them now."

"She ought to taken them," Kate says. "But those rich town ladies can change their minds.Poor folks cant."

Riches is nothing in the face of the Lord, for He can see into the heart."Maybe I can sell them at the bazaar Saturday," I say. They turnedout real well.

"You cant get two dollars a piece for them," Kate says.

"Well, it isn't like they cost meanything," I say. I saved them out and swapped a dozen of them for thesugar and flour. It isn't like the cakes cost me anything, as Mr Tull himselfrealises that the eggs I saved were over and beyond what we had engaged tosell, so it was like we had found the eggs or they had been given to us.

"She ought to taken those cakes whenshe same as gave you her word," Kate says. The Lord can see into theheart. If it is His will that some folks has differentideas of honesty from other folks, it is not my place to question His decree.

"I reckon she never had any use forthem," I say. They turned out real well, too.

The quilt is drawn up to her chin, hot asit is, with only her two hands and her face outside. She is propped on thepillow, with her head raised so she can see out the window, and we can hear himevery time he takes up the adze or the saw. If we were deaf we could almostwatch her face and hear him, see him. Her face is wasted away so that the bonesdraw just under the skin in white lines. Her eyes are like two candles when youwatch them gutter down into the sockets of iron candle-sticks. But the eternaland the everlasting salvation and grace is not upon her.

"They turned out real nice," Isay. "But not like the cakes Addie used to bake." You can see thatgirl's washing and ironing in the pillow-slip, if ironed it ever was. Maybe itwill reveal her blindness to her, laying there at the mercy and theministration of four men and a tom-boy girl. "There's not a woman in thissection could ever bake with Addie Bundren," I say. "First thing weknow she'll be up and baking again, and then we wont have any sale for ours at all." Under the quilt she makes no more of ahump than a rail would, and the only way you can tell she is breathing is bythe sound of the mattress shucks. Even the hair, at her cheek does not move,even with that girl standing right over her, fanning her with the fan. While wewatch she swaps the fan to the other hand without stopping it.

"Is she sleeping?" Katewhispers.

"She's just watching Cashyonder," the girl says. We can hear the saw in the board. It sounds likesnoring. Eula turns on the trunk and looks out the window. Her necklace looksreal nice with her red hat. You wouldn't think it only cost twenty-five cents.

"She ought to taken those cakes," Kate says.

I could have used the money real well. Butit's not like they cost me anything except the baking. I can tell him thatanybody is likely to make a miscue, but it's not all of them that can get outof it without loss, I can tell him. It's not everybody can eat their mistakes,I can tell him.

Someone comes through the hall. It isDarl. He does not look in as he passes the door. Eula watches him as he goes onand passes from sight again toward the back. Her hand rises and touches herbeads lightly, and then her hair. When she finds me watching her, her eyes goblank.

Darl

Pa and Vernon are sitting on the back porch. Pa is tilting snufffrom the lid of his snuff-box into his lower lip, holding the lip outdrawnbetween thumb and finger. They look around as I cross the porch and dip thegourd into the water bucket and drink.

"Where's Jewel?" pa says. When Iwas a boy I first learned how much better water tastes when it has set a whilein a cedar bucket. Warmish-cool, with a faint taste like the hot July wind incedar trees smells. It has to set at least six hours, and be drunk from agourd. Water should never be drunk from metal.