A Marxist History of the World

Counterfire

Series Editor: Neil Faulkner

Counterfire is a socialist organisation which campaigns against capitalism, war, and injustice. It organises nationally, locally, and through its website and print publications, operating as part of broader mass movements, for a society based on democracy, equality, and human need.

Counterfire stands in the revolutionary Marxist tradition, believing that radical change can come only through the mass action of ordinary people. To find out more, visit www.counterfire.org

This series aims to present radical perspectives on history, society, and current affairs to a general audience of trade unionists, students, and other activists. The best measure of its success will be the degree to which it inspires readers to be active in the struggle to change the world.

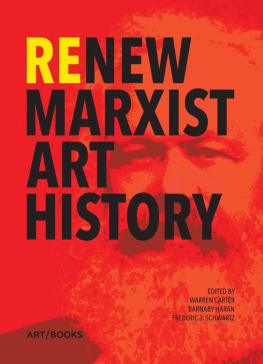

Also available:

How a Century of War Changed the Lives of Women

Lindsey German

Forthcoming:

The Second World War:

A Marxist History

Chris Bambery

First published 2013 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martins Press LLC,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010

Copyright Neil Faulkner 2013

The right of Neil Faulkner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3215 4 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3214 7 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 8496 4863 9 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 8496 4865 3 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 8496 4864 6 EPUB eBook

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the United States of America

Introduction: Why History Matters

History is a weapon. How we understand the past affects how we act in the present. Because of this, history is political and contested.

All knowledge of the present of its crises, wars, and revolutions is necessarily historical. We can no more make sense of our own world without reference to the past than we can manufacture a computer without reference to the accumulated knowledge of many decades. Our rulers know this, and because they have a vested interest in defending their own property and power, they use their control of education and the mass media to present a sanitised view of history. They stress continuity and tradition, obedience and conformity, nationalism and empire. They purposefully underplay exploitation, the violence of the ruling class, and the struggles of the oppressed.

Their version of history has become more dominant over the last 30 years. Past empires, such as the Roman and the British, have been held up as models of civilisation by neo-conservative supporters of imperialist wars today. Medieval Europe has been reinterpreted as an exemplar of the new classical economics favoured by millionaire bankers. Attempts to construct grand narratives of history that is, to explain the past, so that we can understand the present, and act to change the future have been disparaged by fashionable postmodernist theorists who argue that history has no structure, pattern, or meaning. The effect of these ideas is to disable us intellectually and render us politically inert. Do nothing, is the message, because war promotes democracy, there is no alternative to the market, and history cannot be shaped by conscious human action.

This book stands in a different tradition. It is encapsulated in something the revolutionary thinker and activist Karl Marx wrote in a political pamphlet published in 1852: Men [and women] make their own history, but not of their own free will, and not under circumstances of their own choosing. The course of history, in other words, is not predetermined; things can move in a different direction according to what people do. Nor is history shaped only by politicians and generals; the implication is that if ordinary people organise themselves and act collectively, they too can shape history.

This book has its origin in a series first published in weekly instalments on the Counterfire website (www.counterfire.org). It has been extensively revised for book-format publication. This introduction has been added, as has a rather longer conclusion. The short weekly web chapters have been grouped together as the sections of longer book chapters, and each chapter has been given a short introduction. A bibliography has been added so that readers can check my sources and search for further reading, and so has a timeline to help readers keep their bearings through the narrative.

The reorganisation and editing of the original web series should make this a book that can be read cover to cover, but it does not have to be read that way. It should work equally well as a volume of short analytical essays on key historical topics which can be accessed when needed. Either way, it is first and foremost a book for activists for people who want to understand the past as a guide to action in the present.

Many changes are due to the following people, all of whom took time and trouble to read the text, in whole or in part, and offer invaluable critical comment: William Alderson, Dominic Alexander, David Castle, Lindsey German, Elaine Graham-Leigh, Jackie Mulhallen, John Rees, Alex Snowdon, Alastair Stephens, Fran Trafford, and Vernon Trafford. Needless to say, I have sometimes proved stubborn and rejected their advice, so the final result is entirely my own.

A common criticism was that I have neglected certain places and periods; that the book suffers from Eurocentrism, even Anglocentrism. This criticism is justified. I have done my best to correct it, but I have succeeded only in part. The reason is simple and obvious: I am a British-based archaeologist and historian with uneven expertise. Like all generalists, I can never wholly escape the constraints of my training, experience, and reading, and must therefore seek the indulgence and forbearance of readers who are neither British nor European.

Even on the ground I have covered, I suspect I leave a trail of errors and misunderstandings inviting denunciation by diverse cohorts of specialists. That, too, is the inevitable fate of the generalist. There is only one defence. Would correcting the errors and misunderstandings invalidate the main arguments? If so, the project fails. If not if the Marxist approach provides a convincing explanation of the main events and developments of human history irrespective of misconstrued details then the project succeeds.

Hopefully, though, it will achieve something more: it will persuade some that, since humans make their own history, such that the future is determined by what each of us does, they need to get active. For, as Marx himself put it: The philosophers have merely interpreted the world; the point is to change it.

Neil Faulkner

December 2012

1

Hunters and Farmers