CONTENTS

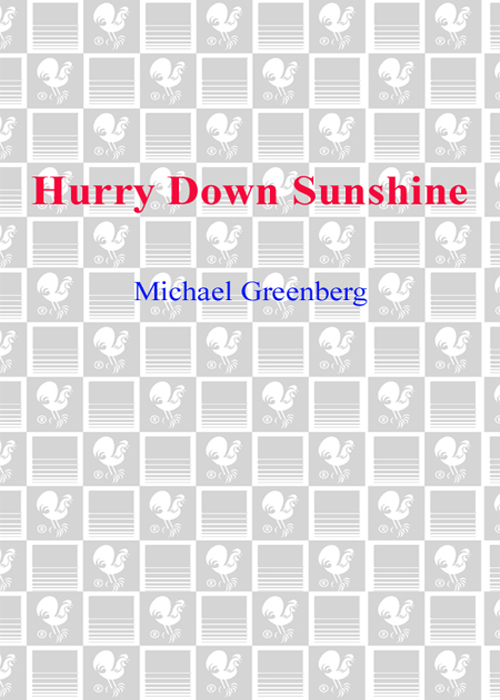

PART ONE

On July 5, 1996, my daughter was struck mad. She was fifteen and her crack-up marked a turning point in both our lives. I feel like Im traveling and traveling with nowhere to go back to, she said in a burst of lucidity while hurtling away toward some place I could not dream of or imagine. I wanted to grab her and bring her back, but there was no turning back. Suddenly every point of connection between us had vanished. It didnt seem possible. She had learned to speak from me; she had heard her first stories from me. Indelible experiences, I thought. And yet from one day to the next we had become strangers.

My first impulse was to blame myself. Predictably, I tried to tally up the mistakes I had made, what I had failed to provide her, but they werent enough to explain what had happened. Nothing was. Briefly, I placed my hope in the doctors, then realized that, beyond the relatively narrow clinical facts of her symptoms, they knew little more about her condition than I did. The underlying mechanisms of psychosis, I would discover, are as shrouded in mystery as they have ever been. And while this left little immediate hope for a cure, it pointed to broader secrets.

Its something of a sacrilege nowadays to speak of insanity as anything but the chemical brain disease that on one level it is. But there were moments with my daughter when I had the distressed sense of being in the presence of a rare force of nature, such as a great blizzard or flood: destructive, but in its way astounding too.

July 5th. I wake up in our apartment on Bank Street, a top-floor tenement on one of the more stately blocks in the West Village. The space next to me in the bed is empty: Pat has gone out early, down to her dance studio on Fulton Street, to balance the books, tie up loose ends. We have been married for two years and our life together is still emerging from under the weight of the separate worlds each of us brought along.

What I brought, most palpably, was my teenage daughter Sally, who, Im a little surprised to discover, isnt home either. Its eight oclock and the day is already sticky and hot. Sun bakes through the welted tar roof less than three feet above her loft bed. The air conditioner blew our last spare fuse around midnight; Sally must have felt she had to bail out of here just to be able to breathe.

On the living room floor lie the remains of another one of her relentless nights: a cracked Walkman held together by masking tape; a half cup of cold coffee; and the clothbound volume of Shakespeares Sonnets, which she has been poring over for weeks with growing intensity. Flipping open the book at random I find a blinding crisscross of arrows, definitions, circled words. Sonnet 13 looks like a page from the Talmud, the margins crowded with so much commentary the original text is little more than a speck at the center.

Then there are the papers with Sallys own poems, composed of lines that come to her (so she informed me a few days ago) like birds flying in a window. I pick up one of these fallen birds:

And when everything should be quiet

your fire fights to burn a river of sleep.

Why should the great breath of hell kiss

what you see, my love?

Last night at around 2 A.M. she was perched on the corduroy couch writing in her notebook to the sound of Glenn Gould playing the Goldberg Variations in a continuous loop on her Walkman. I had come home late after celebrating the completion of yet another hack job in my capacity as a freelance writer: supplying the text for a two-hour video about the history of golf, a game I have never played.

Arent you tired? I asked.

A vigorous shake of her head, a cease-and-desist hand gesture, while the other hand, the one with the pen in it, scuttled faster across the page. Stinging rudeness. But what I felt was a pang of nostalgia for that period in my own life when I did something similar with the poems of Hart Crane: looking up all those alien jazz-blown words, immersing myself in the sheer (and to me virtually meaningless) energy of his language. I hesitated in the living room doorway, watching her ignore me: her almond-shaped Galician eyes, her hair that doesnt grow from her head so much as shoot out of it in a wild amber burst, her hunger for language, for words.

These studious nights, I am convinced, are the release of frustrations that have been building in her since the day, almost nine years ago, when she entered first grade. It may be for the sake of symmetry that I think of that as the day Sallys childhood faded, like the frame in a silent movie where light shrinks to a pinprick at the center of the screen. But that was the way it seemed. She wasnt learning to read, but her difficulties went deeper. The alphabet was a cryptogram: R might as well have been a mouth of crooked teeth, H an upended chair. She had as much success reading The Cat in the Hat as she would a CAT scan. The trick of agreement, of shared meaning, upon which most human exchange is based was eluding her.

It pained me to see this submerged look come over her, as if she had lost her sense of joy. And yet the same words that her eyes could not decipher on the page, her tongue, freed from the fixed symbols of language, mastered with a deftness that allowed for puns, recitations, arguments, speeches, if she deigned to deliver themall attesting to a bewilderingly sharp intelligence.

One day when I went to pick her up at school, the entrance was mobbed with reporters and news crews. A girl in Sallys class had been murdered by her father. With a jolt, the crime reawakened me to the fragility of my six-year-old daughter, the more so because the killer, Joel Steinberg, and I shared a rough physical resemblance. We were both Ashkenazi Jewssame coloring, same height, same glasses. Tribally, I felt implicated in this crime, guilty by affiliation. In the demonic way that once-unimaginable occurrences have of making their replication inevitable, I felt that Sally and I had been hurled into a new level of danger: in America, Tevyes great-grandchildren were murdering their daughters.

I pushed through the news crush and found her standing in the middle of the throng holding a classmates hand. A reporter had thrust a microphone at the girls, fishing for reactions. Sallys eyes rolled up at him. Her coat was on backward, her shoelaces untied. Her barrette was dangling uselessly from her hair like an insect that got caught there. I gathered up the girls and shoved a path through the crowd.

It was around this time that Sallys mother and I split up. We had met in high school and our divorce was like the overly delayed separation of twins: necessary and wrenching. After the upheaval of those months, Sally and I drew closer. I became her advocate, tediously defending her to her teachers, to other parents, to members of our own family flummoxed by the chasm that existed between the way Sally and most everyone else saw the world. Isnt this chasm the very place where imagination thrives? I argued. Isnt it the expression of her access to that sublime region of the mind where none of us matches up ever?

Youre as bright as the rest of them, I assured her. Your intelligence is native, its inside you, just get through these years, life will change, youll see.

And it did change. We traipsed to learning lab, to affordable specialists at a community center in Chelsea. Admitted to Special Ed., she studied rudimentary word sounds and numbers with the tenacity of a scholar trying to learn a lost language. She seemed to be fighting for capacities inside herself that would die if she failed to crack this code. She succeeded and, seizing on the confidence this inspired, was returned to the mainstream, a success of the system. Here the going got rough again, but my promise that sooner or later her dormant talents would spring to life had become credible.

Next page