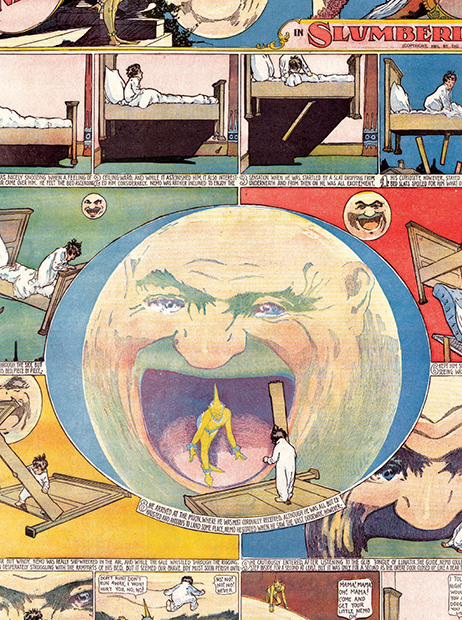

Wide Awake in

Slumberland

Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay

Great Comics Artists Series

M. Thomas Inge, General Editor

The sequence of a dream

will waken our slumber.

subvention by Figure Foundation

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member

of the Association of American University Presses.

Designed by Todd Lape

Copyright 2014 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in Singapore

First printing 2014

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data

available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roeder, Katherine.

Wide awake in Slumberland : fantasy, mass culture, and modernism in the art of Winsor McCay / Katherine Roeder.

pages cm. (Great comics artists series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61703-960-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61703-961-4 (ebook) 1. McCay, WinsorCriticism and interpretation. 2. Fantasy in art. 3. Popular culture in art. 4. Modernism (Art) United States. I. Title.

NC1429.M474R64 2014

741.56973dc23 2013030494

Contents

Introduction

Exploding Boys and Hungry Girls

Picturing Boyhood

Popular Amusement for All

Strategies and Techniques of the Advertiser

The Marriage of Humor and Anxiety

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for this opportunity to write about the singular imagination of Winsor McCay, whose work never ceases to delight, confound, and amaze. I would like to thank Michael Leja and Margaret Werth for their steadfast support of my work. Their keen observations, challenging questions, and probing insights were instrumental to the manuscript. I am indebted as well to Bernard Herman and Patricia Mainardi, for their time and perceptive comments. This book would not be possible without the intellectual and economic support of the Department of Art History and the Office of Graduate Studies at the University of Delaware. I am grateful to Thomas Inge for his faith in this project, as well as Walter Biggins, Katie Keene, and the readers at University Press of Mississippi, whose comments strengthened my work immeasurably.

I am deeply appreciative of the fellowships and grants I received from the following institutions: the Society for the Preservation of American Modernists, the Henry Luce Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies, the Smithsonian Institution, the Caroline and Erwin Swann Foundation at the Library of Congress, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. As a Smithsonian Fellow at the National Portrait Gallery, I found a thoughtful mentor in Wendy Wick Reaves. Cynthia Mills and Amelia Goerlitz at the Smithsonian American Art Museum provided guidance and a great deal of encouragement; while Larry Bird at the National American History Museum was generous with his knowledge of retail holiday displays. At the Library of Congress, Mary Lou Reker kindly found space for me at the Kluge Center. In the Department of Prints and Photographs, Martha Kennedy was a well-informed and gracious guide to the collections. I am indebted to the staffs of the Smithsonian American Art Library, Archives of American Art, the Library of Congress, and the Ohio State Cartoon Library. Paper presentations at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Library of Congress, as well as the annual meetings of the Popular Culture Association and the College Art Association, provided crucial feedback for my argument. I am grateful to Andrei Molotui and Scott Bukatman for their insights and suggestions. The community of Smithsonian fellows was wonderfully encouraging and I wish to acknowledge all my colleagues who took the time to read and respond to portions of this text, including Heidi Applegate, Jobyl Boone, Melody Deusner, Julia Dolan, Katherine Rieder, Sascha Scott, Maia Toteva, Leslie Urena, and Jennifer Van Horn. My Delaware reading groupNikki Greene, Dorothy Moss, Sarah Powers, and Tanya Pohrthas been a source of support since we studied for our major exams together. Our email dialogue about art history, academia, and motherhood continues to be a beacon of inspiration. Thanks to Ana Maria Kozuch, Missy Lemke, Lisa Coldiron, Amanda Spielman, Rod Cumming, Theresa Beall, James Moran, Kathy Carothers, and Drew Marvin for help with everything from babysitting to reading drafts to spotting McCay references (and for knowing when to ask, and when not to ask, about deadlines).

Lastly, I thank the Howard and Roeder families for their patience and love. Valerie Howard allowed me to write by providing countless hours of childcare. Her generosity is humbling. Thank you to my sisters and brothers, in-laws and out-laws, nieces and nephews. My parents, Catherine and Alexander Roeder, cultivated my love of literature and history, and fortified me with their boundless faith and unconditional support. Zachary Howard has been my primary editor and sounding board. My book, and my life, is profoundly richer as a result. I am indebted to my own little Nemos, Alexander and Violet. Their imagination, excitement, and wide-eyed wonder inspire me every day. With gratitude, I dedicate this book to my family.

Wide Awake in

Slumberland

Introduction

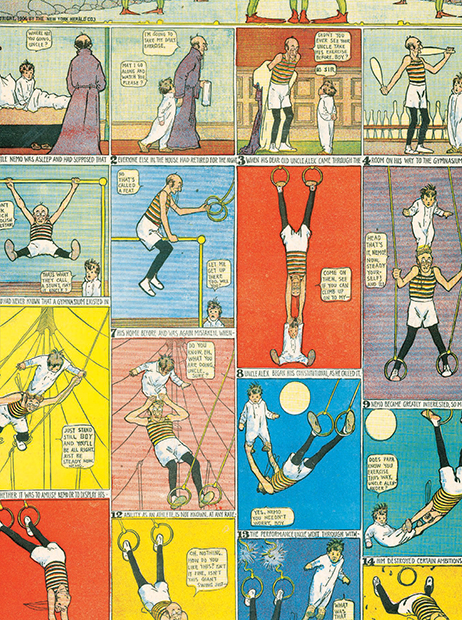

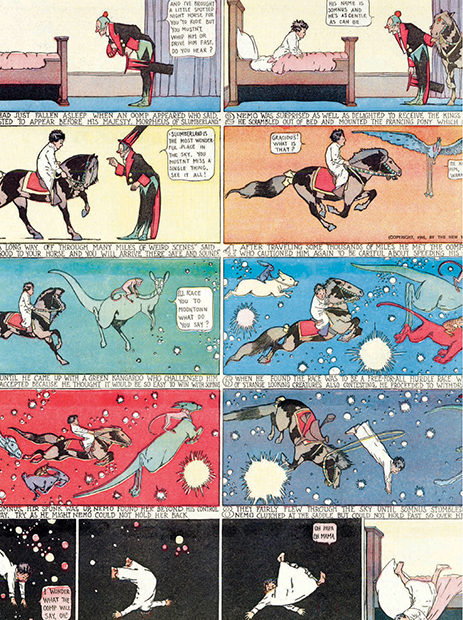

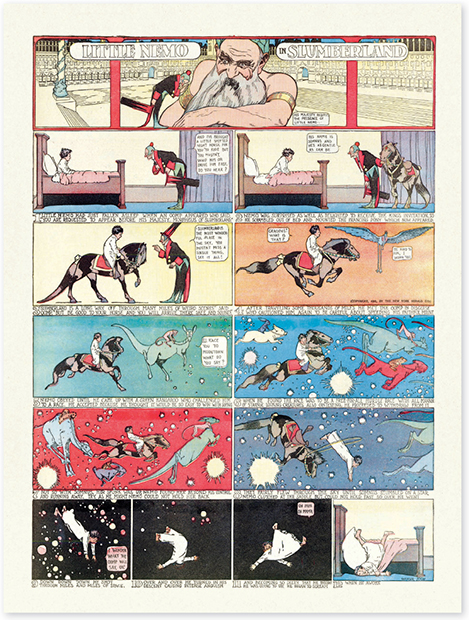

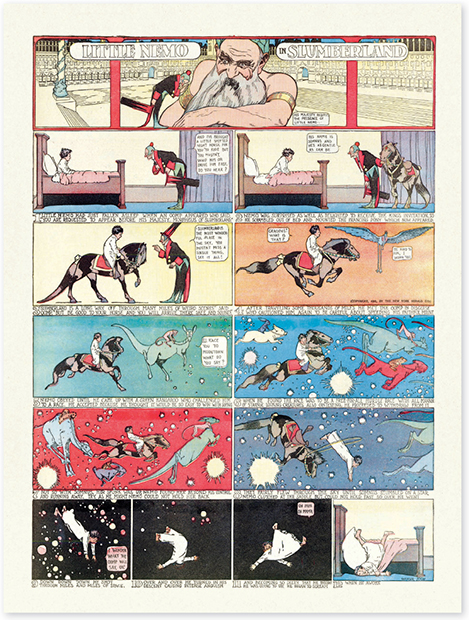

A young, tousled-haired boy about the age of six is sitting upright in his bed, ensconced in a non-descript, middle-class bedroom (). His sleep has been interrupted by the appearance of a green-faced clown, deeply bowing before him in a top hat and tails, and imploring the youngster to travel with him to an enchanted, faraway kingdom. And with that solemn yet magical entreaty, so begins Winsor McCays epic comic strip adventure, Little Nemo in Slumberland.

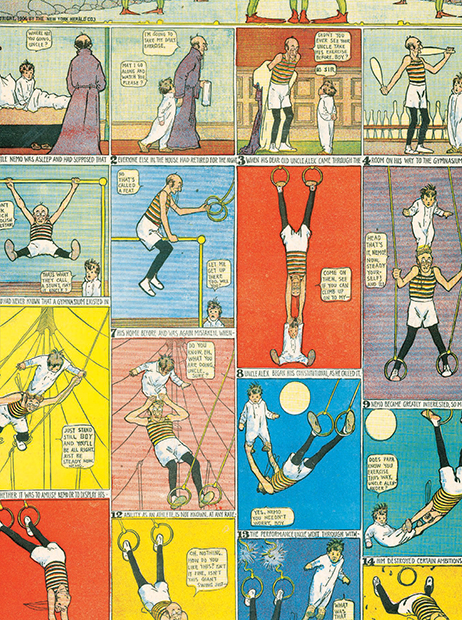

In the daily and Sunday editions of American newspapers, McCay created elaborate narratives of anticipation, abundance, and unfulfilled longing. His comics redefined the medium at a decisive historical moment and made a lasting contribution to the proliferation of fantastic imagery at the dawn of the twentieth century. He successfully translated the experience of modernity into a visual language and, in the process, shaped an audience for his work. Little Nemo in Slumberland was a weekly comic strip in which the title character repeatedly embarked on epic journeys to exciting, strange, and sometimes frightening places, only to awaken in the last frame safe in his bed at home. In McCays other major comic, the sophisticated and cynical Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, a succession of hapless dreamers was subjected to nightmarish visions of everyday modern life only to awake, like Nemo, to reality in the final panel.

Fig. 1.1

Winsor McCay, Little Nemo in Slumberland, New York Herald, October 15, 1905, Courtesy of Peter Maresca and Sunday Press Books

If anything, the false dichotomy between mass culture and modernism has served to promote cultural hierarchies that have yet to be fully dismantled.