Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Saguisag, Lara, author.

Title: Incorrigibles and innocents : constructing childhood and citizenship in progressive era comics / Lara Saguisag.

Description: New Brunswick : Rutgers University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003851| ISBN 9780813591773 (hardback) | ISBN 9780813591766 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Comic books, strips, etc.United StatesHistory and criticism. | Children in literature. | Citizenship in literature. | Literature and societyUnited StatesHistory. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Popular Culture. | LITERARY CRITICISM / Comics & Graphic Novels. | HISTORY / Social History. | PERFORMING ARTS / Film & Video / History & Criticism. | HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Childrens Studies. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Gender Studies.

Classification: LCC PN6725 .S35 2018 | DDC 741.5/973dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003851

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2019 by Lara Saguisag

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, N.J. 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

Drawing the Lines

Richard F. Outcault made a living by drawing children. As a cartoonist and illustrator who witnessed and experienced the turbulences and dynamisms of New York City in the Progressive Era, he produced quite an assortment of images of childhood: immigrant and working-class boys and girls who played riotous games in back lots, alleys, and parks; white, middle-class youngsters who threw tantrums and sowed chaos in the parlor; and black children who were, troublingly, modeled after the popular pickaninny caricature. In his newspaper comicswhich ran the gamut of single-panel cartoons, large cartoons divided into multiple sections, and multipanel sequential stripshe coaxed readers to sympathize with doleful waifs, admire the resourcefulness of bell boys and street urchins, and chuckle at the sight of city kids who found themselves out of sorts in the countryside. Outcaults persistent fascination with childhood obviously paid off: his work made him a fortune and turned him into a national celebrity. In his lifetime, critics hailed him as the father of the funnies. His contemporaries sought to replicate his success by launching their own child-centered comics series. Many comics historians and archivists regard Outcault as an innovative, astute artist who helped lay the foundations of the American comic strip.

The case of Outcault demonstrates that the theme of childhood was essential to the emergence and development of comics in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But this book does more than just examine Progressive Era cartoonists exploration of and fixation with childhood. It also reveals that the two strands of comics and childhood were tightly braided with contemporary discourses of citizenship and nationhood. The Progressive Era was a period defined by conflictsbetween industrial and agrarian economies, workers and the wealthy, emancipation and white supremacy movements, immigration and nativism, the New Woman and the Cult of True Womanhoodand cartoonists used images of children to explore, dissect, and sometimes defuse these sociopolitical tensions.

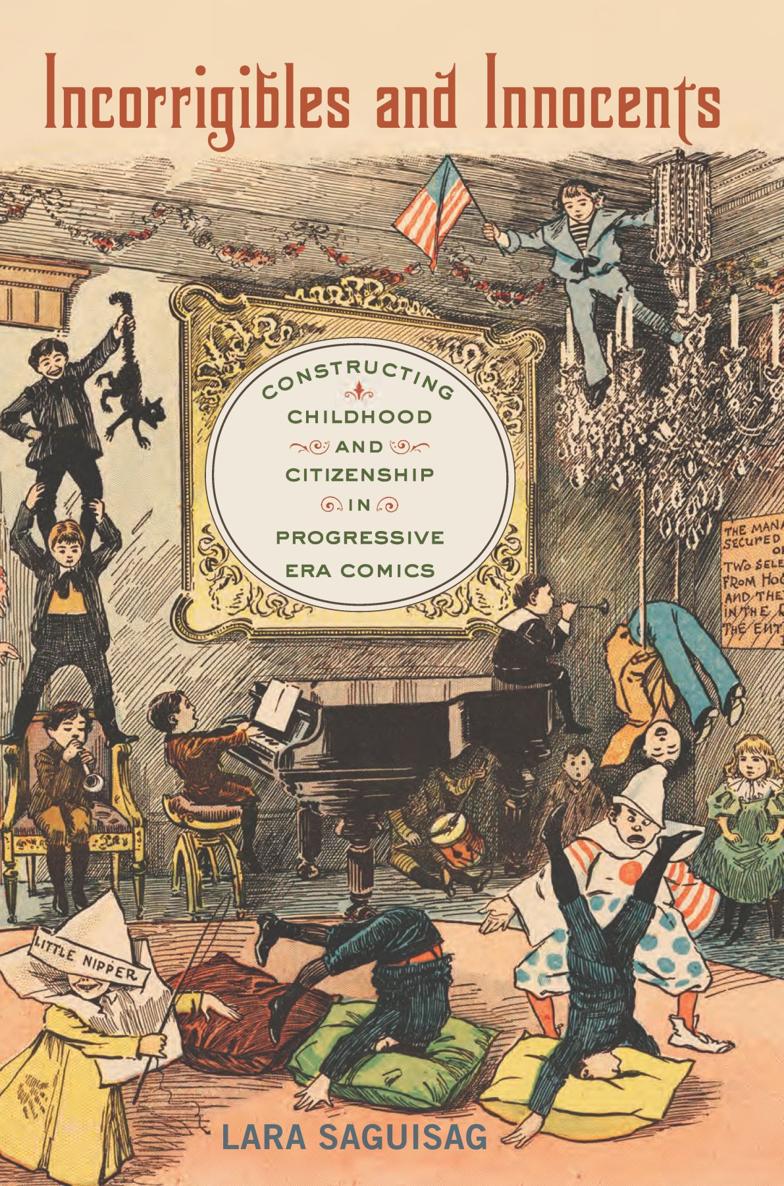

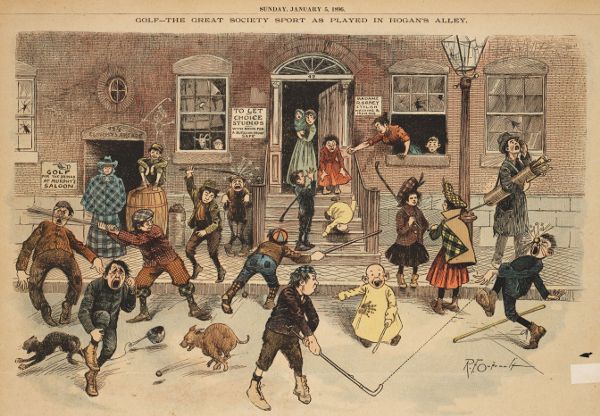

Turn-of-the-century readers likely apprehended Golf as a visual shock as they confronted the cartoons size, mix of colors, and intricate network of actions. Of course, the themes and techniques of Golf were not at all atypical for its time. Like many of his contemporaries, Outcault used images of swarming immigrant and working-class youth as shorthand for the tumult and unpredictability of city life. In fact, in drawing Golf, Outcault walked a path that he had repeatedly tread, as made evident by his earlier work published in the

Figure 1. Cartoon by R. F. Outcault. Golfthe Great Society Sport as Played in Hogans Alley. In New York World Comic Supplement, January 5, 1896. SFS 58-1-1, San Francisco Academy of Comic Art Collection, the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum.

The yellow nightshirt, however, is not the only thing that makes the character distinct. What is more arresting is his interaction with his audience. Not only does he meet the readers gaze; he also uses his right hand to instruct her where to look. His expression of amusement also prompts the reader to delight in the various scenes of chaos that play out in Golf. While most of the figures in the panel remain anonymous, the boy in the yellow smock steps out of the realm of stock characters, emerging as a distinct, memorable individual. Outcault later recognized the commercial potential of his character and made the move to further signal this fictional childs singularity by giving him a name. Outcault christened his creation Mickey Dugan. The public, however, took to calling him by another name: the Yellow Kid.

Comics historians note that this kid played a definitive role in the development of comics, consumer culture, and journalism at the turn of the century.

The Yellow Kid series also played a vital role in the expansion of consumer culture at the turn of the century. The characters success gave publishers confirmation that the comic supplement was crucial to boosting newspaper circulation. The Yellow Kid also inspired an unprecedented consumer craze in New York City. The character swelled from a two-dimensional figure to a commercial

Because of his extraordinary lucrativeness, the Yellow Kid became a pawn in the well-documented newspaper feud between Pulitzer and Hearst. When Outcault left to work for Hearsts Journal, Pulitzer hired the artist George Luks to continue drawing Hogans Alleyand the Yellow Kidfor the World. Consequently, for a brief period, two competing series featuring the Yellow Kid appeared simultaneously in two papers, with each publication insisting they owned the rights to Outcaults character.

There is, however, a curious omission in the rich body of histories and criticism that consider and debate the significance and impact of the Yellow Kid. Very few scholars have expressed interest in investigating why Progressive Era readers and consumers so avidly embraced a fictional child and why, in the wake of the Yellow Kids success, child characters proliferated in newspaper comic supplements. Just as the Yellow Kid appeared in the foreground of Golf, child characters stood front and center in many turn-of-the-century newspaper supplements. Cartoonists such as Outcault, Rudolph Dirks, James Swinnerton, Winsor McCay, and Grace Wiederseim, among many others, built their careers on series headlined by children. Fictional children such as Buster Brown, Hans and Fritz Katzenjammer, Little Jimmy, Dear Katy, Little Nemo, and Dolly Dimple entertained and captivated many Progressive Era readers. Yet comics scholarshipwith a few exceptionscontinues to overlook the importance of childhood and child characters to the development of newspaper comics in the United States and, more broadly, of comics in their various iterations around the world.