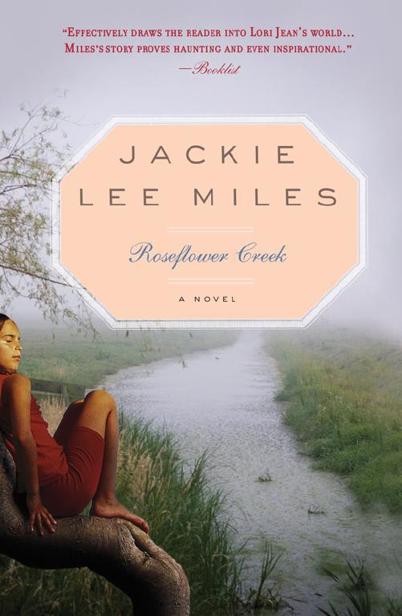

Copyright 2003, 2010 by Jackie Lee Miles

Cover and internal design 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc. Cover design by Jessie Sayward Bright

Cover images Colin Gray/Getty Images; Scott Higdon/Veer

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Cumberland House, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miles, Jackie Lee.

Roseflower Creek / by Jackie Lee Miles.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Problem familiesFiction. 2. Rural conditionsFiction. 3. Georgia Fiction. 4. Domestic fiction. I. Title.

PS3613.I53R6 2010 813'.6dc22

2009050312

Prologue

The morning I died it rained. Poured down so hard it washed the blood off my face. I took off running and kept going 'til my legs give out and I dropped down in the tall grass by the creek. The ground was real soggy; my shoulders and feet sunk right in. I curled up on my side and rocked my tummy and sucked in that Georgia red clay 'til it clung like perfume that wouldn't let go. Mud cakes and dirt cookies, some I'd baked in the sun just yesterday, filled my nose. They danced all blurry above me, inviting me back to their world a' make-believe. That one mixed with laughter and pretend, sugared all nice with wishes and dreams. I reached out to grab 'em, to get back to that place where they was, but the pain held me tight in a blanket of barbed wire. And them cookies, they plumb disappeared.

My arm was busted. My spleen was teared. My 'testines was split and my windpipeit was pretty much broken up, too. I didn't know most of those words, not then. I saw 'em in the paper the very next day. I stood over my mama and watched her cry on the newspaper the sheriff man brought to her cell. All I knew was it hurt, that day in the grass. It hurt so bad, it like ta' killed me. I prayed for it to endI did . I sure enough did.

He come looking for me then, my stepdaddy, Ray. Called out to me, his voice filled with liquor.

"Lori Jean! You git back here! Ya' hear me?" he said. I heared him, but I didn't answer. It made him crazy in the head.

"Ya' hear me, girl? You ain't had a beatin' like I'm gonna give ya'," he said. 'Course, he was wrong. He just give me one.

He found me then; stumbled over me in the grass. He yanked me up by my hair, but I didn't move. Then he grabbed my arm, that broken one. It was twisted like a bent stick. He must not of seen it though, 'cause he didn't pay it no mind. But, not to worry. It didn't hurt no more. Nothing hurtit was mighty peculiar. Truth be known, I felt pretty good right about then. Kind of floating on a cloud, I was.

"Why do ya' do this to me, huh?" he said. He was so mad. He tried to drag me back to the trailer where we lived. That's when he seenI couldn't walk. I couldn't breathe. He sure changed his tune. He started crying and carrying on, shaking me all about.

"Lori Jean, honey, wake up! Wake up, honey!" he yelled.

Then he dropped on down to his knees; he was holding me so nice. He had his arms wrapped all around me and he was hugging me to his chest, just like a regular daddy, just like I always wanted him to. He was crying real tears. He was! And he was praying, too, right out loud.

"Oh Jesus!" he said, and he cried even harder. It was so sad.

"Oh my girl, my sweet baby girl," he said over and over. He was carrying on and hugging me so nice. I wanted to hug him right back, but my arms and legsthey wouldn't move nohow.

"What have I done to you, girl?" he asked, maybe thinking I could answer. And then he started praying again and that was really something 'cause he never been one to pray much, even though my mama tried to get him to and drug him off ta' church ever' chance she got.

"Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, what have I done?" he said, and he picked me up.

I watched him carry me on down to Roseflower Creek and dump me in the water. So here I am, floating on a cloud, floating in the river, right in the middle of the creek! It's real pretty here. A body might could grow to like this even. Real peaceful like, it is. If 'n my meemaw was here, she'd say, "This is plain out, plumb nice." And she'd be dead right. 'Cause that it is. That it sure enough is.

Chapter One

My real daddy left in August when I was five on a day so hot they was giving out free fans. Drove away in our old pickup truck the color of money, which was God-ronic my meemaw said, since he ne'e r had any. I don't remember much about my pa, but I remember that truck. He let me ride in the back whenever we drove to town. Like to throwed me out a couple a' times, but I loved it, being too little to realize a body could get killed that way. It was my favorite thing to do and the funnest, us not having much money for regular fun things.

"Headed to Atlanta," Daddy said that day. "Had enough a' yer' ma's bellyaching for sure."

She run after him, my ma did, her belly jiggling with a baby inside. Didn't do her no good. Daddy kept on going 'til he was a speck the size of the fleas that drove Digger nuts. Mama throwed herself off a ladder that night, from the hayloft in old man Hawkins's barn. She lived. Sprung her ankles is all. Both of 'em. But that baby, it died. It come out in the tub. That's when I seen it was a baby brother she had growing in there, 'cause I peeked.

Mama cried a long time, but not for the baby I don't think. It was my daddy she wanted. She didn't mention that baby again, even when I growed older. Didn't name him or visit him like me and MeeMaw did. MeeMaw called him Paul after that guy in the Bible the preacher liked to talk about most Sundays. I called him Paulie. Seemed only right, him being so little. Truth be known, I'da rather had a sister. But a brother'd been okay.

The ladies at church said my daddy was no good; on a "slow train to hell," they said. I don't know; he was going real fast when he left. They said he had a girl over in Athens. 'Course that was a lie. I was his only girl. He told me so.

"You're my girl, Lori Jean," he said. "My only girl. And don't you forget it, okay?" he told me every time I sat in his lap.

'Course I never did understand him running off and leaving me with Mama. She didn't seem to want me much, either. 'Least she didn't throw me off no ladder. Poor Paulie. MeeMaw put him in a shoebox and tied it with the piece of blue satin ribbon she was saving for something special and this was something pretty speciala little dead baby boy never did no harm to no one and him being put in a shoebox and a mama that didn't cry over him or nothing.

The church folks let us bury him in a grave spot we didn't have no money for, which was real nice of them, so I forgive 'em right then for saying that stuff about my pa and that girl. We buried Paulie in the back, over by the kudzu. MeeMaw, that's what I call my grandma, and me would visit him on holidays and sometimes after Sunday service if the message moved her and her arthritis didn't hurt her too much to walk the extra steps.