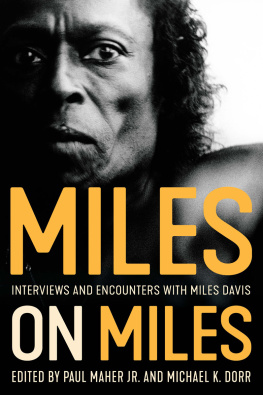

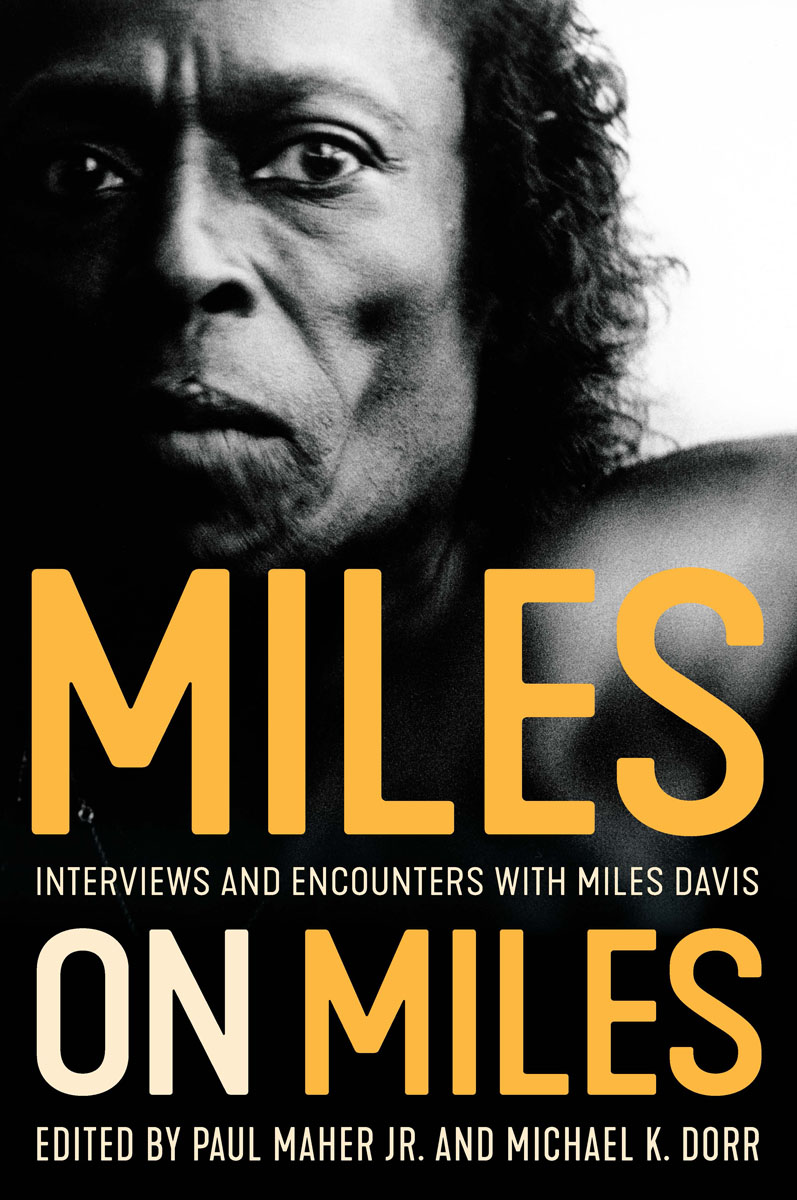

Copyright 2009 by Paul Maher Jr. and Michael K. Dorr

All rights reserved

First hardcover edition published 2008

First paperback edition published 2021

Revised electronic edition published 2021

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-64160-467-3

Hubert Saal, Miles of Music, from Newsweek, George Goodman Jr., I Just Pick Up My Horn and Play, from New York Times, and Ben Sidran, Miles Davis, from Talking Jazz: An Oral History 43 Jazz Conversationsare only available in the print edition of this book.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Miles on Miles : interviews and encounters with Miles Davis / edited by Paul Maher Jr. and Michael K. Dorr.

p. cm.

Description: Revised electronic edition. | Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Note: Miles of Music with Hubert Saal from Newsweek, I Just Pick Up My Horn and Play with George Goodman Jr. from New York Times, and Miles Davis with Ben Sidran from Talking Jazz: An Oral History 43 Jazz Conversationsis only available in the print edition of this book.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781556527067 (hardcover) |ISBN 9781641604673 (paperback) | ISBN 9781641606004 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781614606028 (mobi) | ISBN 9781641606011 (epub)

1. Davis, MilesInterviews. 2. Jazz musiciansUnited StatesInterviews.

I. Maher, Paul, 1963 II. Dorr, Michael K. III. Title.

ML419.D39A5 2008 788.92165092dc22

2008014067

To David Amram

Master musician, true friend, and inspiration

PAUL MAHER JR.

To Samuel Menashe

Poet and friend

For all the right reasons

MICHAEL K. DORR

CONTENTS

March 23, 1970Miles of Music

Interviewer: Hubert Saal, Newsweek(Print Edition Only)

June 28, 1981I Just Pick Up My Horn and Play

Interviewer: George Goodman Jr., New York Times(Print Edition Only)

January 1986Miles Davis

Interviewer: Ben Sidran, from Talking Jazz: An Oral History43 Jazz Conversations(Print Edition Only)

INTRODUCTION

Some called him the Prince of Darkness or the Picasso of Invisible Art. He was the consummate rebel, exuding the daunting aura of the Prince of Silence or even Mr. Dont Call Me Cool. All of these monikers, however, contradict the man who brightens these pages with canny insights and droll humor as he expounds his philosophy about the skewed social order of his world. There is the mediocrity and the genius of his musical peers, his hatred of racism, his insistence that the word jazz is nothing more than a pejorative term for niggers: Jazz is a nigger word, he states to an unsuspecting interviewer. As if what Miles thinks about the word jazz is sheer nonsense, the interviewer goes on using the word anyway for lack of a better way to classify Daviss music. And for certain, much of what Miles did accomplish is unclassifiablemuch like the man himself.

Most times, Miles comes across as anything but the Prince of Darkness: hes bright, comical, brutally honest, intelligent, in control, and entirely at ease even in the most trying or inauspicious occasion. He is honest to the extreme, so much so that at times he becomes graphic about things like sex, his copious heroin use, his short period playing the pimp. Then theres his constant vernacular mainstaymotherfucker. He plays like a motherfucker, my band is a bunch of motherfuckers, those guys are dirty motherfuckers, my legs hurt like a motherfucker during that tour, shes fine as a motherfucker. His language is colorful, leaving intact the vocabulary of a Midwestern black man from East St. Louis, raised in a middle-class household. He studied for a while at Juilliard, but absorbed the bulk of what he learned from the city streets, within the din of smoky Harlem clubs, or from watching on the sidelines the true masters of the form: Charlie Bird Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, and Dizzy Gillespie.

After a tour of duty with Parker, Miles was ready to leap forward confidently, a flashy zeal in his tailor-cut Italian suit, from under Duke Ellingtons elongated shadow. Ultimately, and conscientiously, by not Uncle Tomming to his audience, by not grinning like Louis Armstrong or performing upon a shoeshine box, he swore musical fidelity to self-respect, not only for what he was accomplishing but also because he, too, was a valid card-carrying member of the United States of America. He shone a whole new light upon his race. If Adam Clayton Powell was dazzling at the pulpit, then Miles Davis dominated the stage. He played with authenticity, with feeling, always challenging the audience not to underestimate just what he was doing when his back was turned away from them under his lonesome spotlight. He didnt have to be poor and play his horn from the broken stairs of a southern chicken-shack to play the blues. His contribution was just as valid as those Mississippi Delta bluesmen who had forged the genre decades earlier.

Being a musician, oftentimes he wanted to discuss anything but music, because his music said everything he wanted to say by virtue of its existence. He hated discussing his past and despised detailing his guiding aesthetic. Most times he directed the topic toward his band members, as in Herbie plays like a motherfucker. This presents an undeniable challenge for the interviewer: either face the likely prospect of disdain for pursuing the role of an intrusive journalist or charge determinedly into the dark abyss hoping to emerge from the other side unscathed (and with enough material to complete the assigned article). When this doesnt work, writers instead describe Miless surroundings or mannerisms or strive to capture his quick, deft sketching on a drawing pad. More banal is the avid attention the interviewers sometimes devote to how he eats, orders his food, or even how he breathes. In all of these things there lurks a distinct personality. Davis, for all of his quirks and foibles, comes across as a genius of musicbut not of life.

A constant searing theme of these pages is racism in all its insidious incarnations. Americafrom the year of Miles Daviss birth in 1926 until his death in 1991 (and beyond)still judged people on the basis of their skin color rather than on the content of their character. Although government laws and constitutional amendmentsdating from shortly after the Civil Warassured civil rights on paper, the pernicious air of racial prejudice still permeated Americas streets. It wasnt going away anytime soon, if ever, and Miles knew it. His love for Ferraris and women (white women) made certain that his most envious detractors, enraged by his constant affronts to white entitlement, would cause the trumpeter incessant hassles.

When he was a boy, a white man calling him nigger chased him down the street. It was a hateful memory that echoed through the years, always resurrecting in an instant that harsh realization and harsher reality. Although critics, fans, and fellow musicians viewed him as an important and groundbreaking composer/bandleader/performer, whites waiting for Miles to entertain them still thought of him (as related in many of the following interviews) as just a nigger. The bitter diatribes Miles unleashed concerning racism succeed more in revealing the depths of his sensitivity than in labeling him as a ranting anti-white bigot. David Amram, who knew Miles as an acquaintance from 1956 until his death in 1991, remembers well that sensitivity. One rainy night in 1956 Miles entered the Caf Bohemia. Amram decided to play it cool and not bother the man whod successfully captured everyones attention and brought the bustling nightclub to a standstill. As he walked by, Amram caught a glimpse of Davis looking toward him from the corner of his red-rimmed eye, carefully considering him from behind his trademark impenetrable sunglasses. What Amram saw wasnt contempt but a steely gaze of hurt.

Next page