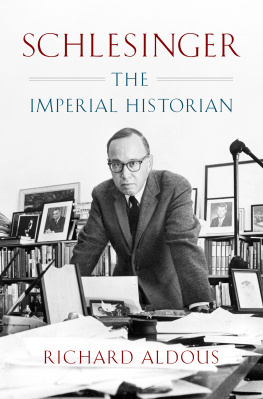

Minutes to Midnight:

Twelve Essays on Watchmen

edited by

Richard Bensam

Sequart Research & Literacy Organization (Edwardsville, Illinois)

Copyright 2011 by the respective authors. Watchmen and related characters are trademarks of DC Comics 2011.

Kindle edition, January 2012. First edition, October 2010. Revised first edition, November 2011.

All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts used for review or scholarly purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including electronic, without express consent of the publisher.

Cover by Kevin Colden. Design by Julian Darius. Interior art is DC Comics; please visit dccomics.com .

Published by Sequart Research & Literacy Organization . Edited by Richard Bensam.

For more information about other titles in this series, visit Sequart.org/books/ .

Contents

Obsolete Models a Specialty:

An Introduction

by Richard Bensam

The British comics artist and comics historian Steve Whitaker once described a conversation he had with Dave Gibbons at a comics convention in the fall of 1986, sometime not long after the fourth issue of Watchmen was published. Whitaker had been following the series very closely, of course, and as a careful reader believed he had discovered the key to the story. So when he ran into Gibbons at the convention, he asked the Watchmen artist, Rorschach is the real center of the story, isnt he? Hes the character we should be keeping our eyes on, the one everything else revolves around, right?

As Whitaker told it, Gibbons shook his head and replied, Thats not it. There isnt meant to be one central character. The whole point is that everyone gets to choose the character they want to follow. It could be Rorschach or the Comedian or Ozymandias. You could be Nite Owl. Retelling the story later, Whitaker claimed he was never entirely sure if the Watchmen artist had compared him to Nite Owl because he saw something of Dan Dreibergs personality traits in Whitaker or if this was Daves tactful way of hinting that Steve was putting on weight.

That question may never be answered, but Ive often thought about that anecdote in the years since then not least because Nite Owl was always my guy as well. In fact, I always imagined he was the overlooked central character in Watchmen .

Its true that Nite Owl doesnt narrate his own life story over the course of an issue, as the other living heroes in Watchmen do. Nor do we see him extensively in the recollections of others, as we do with the late Comedian. From his lack of prominence in the stories recounted by the other leads, Dan Dreibergs most distinguishing trait seems to have been that most of the other costumed heroes didnt have any strong feelings about him one way or the other. And yet, hes the one who makes the resolution possible by deciding to free Rorschach from prison; hes the one who does the research that ultimately discloses their real adversary; and hes the one who gets the girl and lives happily ever after. That list of accomplishments certainly befits the hero of the story, wouldnt you think?

But theres another reason for Nite Owl to hold our attention, and it takes us back to the above anecdote and leads us directly to the point of this whole book. Consider:

The first thing we learn about Nite Owl in the first issue of Watchmen is that he idolizes the masked heroes of a previous era. He has a home full of costumes, accessories, memorabilia, and collectibles. The very thing that gives his life meaning is something he often feels embarrassed about. He needs to keep it secret and hidden or risk harassment and humiliation. Being able to admit his feelings at last to other people who share his interests comes as a profound relief. When he becomes friends with the man whose exploits inspired him and is briefly able to follow in his footsteps, hes over the moon. Lets face it if they held conventions of costumed hero enthusiasts in the world of Watchmen , Daniel Dreiberg would happily attend. If some toy company had issued action figures of the Minutemen, Daniel would have the complete set on display in a glass case somewhere in his Manhattan townhouse.

In other words, Dan Dreiberg is the perfect analog of a comics fan. His friendship with Hollis Mason is much like that of a fan who corresponds with and befriends his or her favorite creators. Hollis can certainly be considered the creator of his Golden Age costumed identity as the original Nite Owl. Extending that analogy slightly further, we might even say Dreibergs fandom takes the form of wishing to create his own exploits also very much the case in comics fandom, where many fans aspire to become pros.

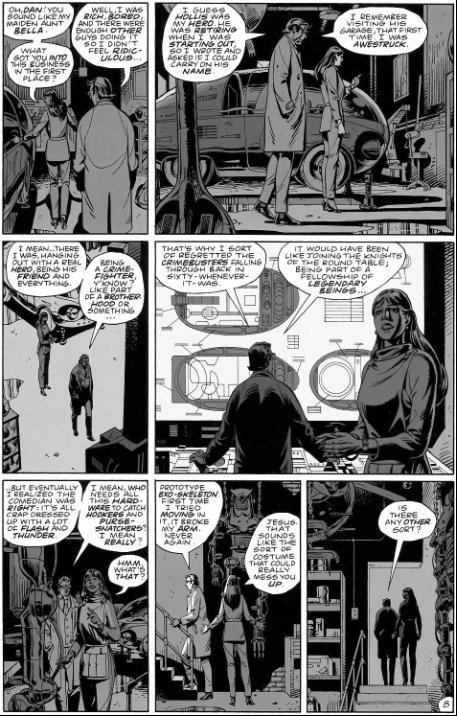

Archetypal fan Daniel Dreiberg shows Laurie Juspeczyk his collectibles and souvenirs. From Watchmen #7 (March 1987). Copyright DC Comics.

Taking all of this into account, Nite Owl would inevitably seem to be the natural viewpoint character for a comics reader the ideal audience surrogate, our perfect window into the events of Watchmen . Hes the devoted fan who loved costumed heroes and wanted to live in that world and finally did, only to find himself unfulfilled and let down. Doesnt this dilemma cut right to the goal of Watchmen bringing a more mature and sophisticated outlook to bear on the nostalgia-drenched trappings of super-hero comics?

Thats how its always seemed to me. So imagine my consternation if a student of the history and philosophy of science were to say that the real goal of Watchmen is the illustration of post-Einsteinian physics as literary metaphor, and therefore Doctor Manhattan is obviously the central figure and most important character in the story.

Were both right, of course. But youd also be right if you said Watchmen was really all about using the super-hero genre to satirize the arrogance of American foreign policy and that the Comedian was the pivotal character. Or if you argued Silk Spectre was the real viewpoint character the sole relatively balanced and normal person among damaged personalities, bent and twisted in various ways by the super-hero concept; the one who shows us how disturbing and neurotic it all looks when you take a step back and see the bigger picture. Or if you said Ozymandias represents us when he sits in front of his wall of television screens seeking hidden meanings in brightly colored images while his eyes dart constantly from rectangular frame to rectangular frame, feeling himself above everyone else as he tries to discern the end of the story. Remind you of anything?

These answers (and many others besides) are all equally correct. One can even imagine these answers forming the basis of some sort of personality test, something along the lines of asking someone to name his or her favorite Beatle and using that selection to discern something fundamental about that persons outlook. But in Watchmen, these different viewpoints mean something more than a Rorschach blot, if you will, or a chance to play Choose Your Own Adventure. The fact that there are so many different possible interpretations is the whole point; its not which one you choose that matters, its that you have the choice. As Jon Osterman would tell you, there is no privileged frame of reference, no one right way to look at the universe. Everything is only relative to everything else. This is precisely what Dave Gibbons was saying back in 1986. And in an interview with George Khoury for the career-spanning overview The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore in 2002, Watchmen writer Alan Moore answered the same question in much the same way: