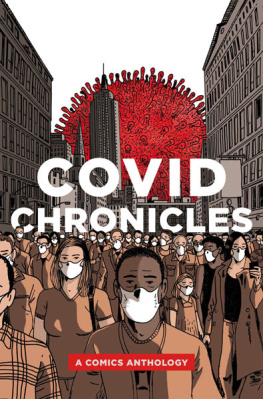

COVID Chronicles

This book is dedicated to our frontline workers and to those who lost their lives to COVID-19.

CONTENTS

October 2020

What can we draw out of this moment, when words fail us? In early April, when COVID-19 cases spiked in the US and life as we knew it slipped quietly from view, I sent out a call for short comics to see how comics creators were responding to the pandemic. COVID comics have gone viral these past months on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Digital publications like The Nib and anthologies such as Heroes Need Masks have collected and published pandemic-themed comics. It turns out that comics creators have had a lot to say in these exceptional times. This volume, COVID Chronicles, was compiled over the course of six months, from mid-April 2020 to mid-October 2020. It comprises sixty-four short comics that were sent in response to the call or were solicited expressly for this anthology, and in some cases, we have included comics we discovered online. The comics here run the gamut in perspective and style. Some are true, deeply personal stories; others are invented ones, either based on real events or inspired by a vivid imagination. They are documentary, memoiristic, meditative, lyrical, fantastic, and speculative, offering a view onto the countless ways the COVID-19 pandemic has changed lives.

There are comics here about getting COVID-19 and recovering from it, about losing someone to it, adjusting to home schooling, being furloughed, working the front lines, getting evicted, reliving past trauma, witnessing police brutality, and protesting for social justice. We see how world leaders measure up (or not) in their efforts to manage the pandemic. As a character in Kay Sohinis Pandemic Precarities says, this pandemic has exposed and amplified everything that is wrong with our world. It has exacerbated economic inequalities, inadequate healthcare systems, social injustice, racism, xenophobia, and political hegemony, all of which are pervasive themes in these comics. In short, these comics reveal the pure fear, anxiety, and grief so many of us are experiencing these daysfeelings that will no doubt be with us for years to come.

Strange, perhaps, for these emotions to resonate so clearly in a medium that people often assume is either directed toward children or there for our amusement. But comics have a history of tackling weighty and mature subjectsand doing it well. Comics expert Hillary Chute reminds us that disaster is deeply rooted in comics, whether its in the superhero comics of the Silver Age (from the late 1950s through the 60s), where the plot often revolves around some calamitous ordeal for the protagonist, or in the themes of more recent nonfiction comicsa classic example being Art Spiegelmans Maus, which retells his fathers experience in the Holocaust. With the underground movement of the 1960s and 70s and the rise of alternative comics that took on controversial and taboo topics, the medium has shown itself to be particularly well suited to expressing difficult subject matter. As Chute points out, comics [make] readers aware of limits, and also possibilities for expression in which disaster, or trauma, breaks the boundaries of communication, finding shape in a hybrid medium.

Fast-forwarding to the twenty-first-century comics scene, a more recent movement known as graphic medicine has looked to comics to articulate complex or unsettling ideas, especially as they relate to important issues surrounding illness, disability, and healthcare. The term was coined in 2007 by UK physician and comics artist Ian Williams (also a contributor to this volume). Graphic medicine began as an area of study for scholars, educators, practitioners, and artists who saw in the subversive power of comics the ability to challenge prevailing attitudes toward the disabled, the ill, the dying, and those who care for them. In time, and quite rapidly, graphic medicine grew into a movement and a diverse community that includes not only scholars, educators, and practitioners but also people who create comics, people with illness and disabilities, family caregivers, medical students, librarians, and publishers. The movement became as much about the creation and dissemination of comics as about the study of comics, about merging the personal with the pedagogical, the subjective with the objective, with the goal of making and using comics to effect cultural change.

Penn State University Press brought graphic medicine to its list when Susan Squier, now Brill Professor Emerita of English and Womens, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Penn State University, introduced me to the crossdisciplinary intersection of comics and medicine. Over the course of a distinguished career in the medical and health humanities, Squier made space for comics in her scholarship and teaching, because they enable us to enter, imaginatively, a number of complex, ambiguous debates.

This book, COVID Chronicles, now launches a trade graphic novel imprint at Penn State University Press called Graphic Mundi. In fact, a book like COVID Chronicles is a great example of how graphic medicine so effectively conveys ideas of scale and connection. Documenting what people have experienced for more than half of 2020, it is, to date, the most comprehensive collection of comics about the pandemic. It reveals the shifting scale of the pandemic over time, illustrating how the actions of an invisible microbe have led, in the space of just months, to systemic upheaval, such that we find ourselves now struggling to comprehend the greatest medical, economic, political, and social challenges many of us have had to face in our lifetimes.

COVID Chronicles also demonstrates the power of comics to make connections, whether its helping people connect their own thoughts in difficult circumstances or helping them connect with one another. Characters in these comics use drawing as a way to think and feel on the page[, to] try and make some sense of all this, or they imagine themselves as a comic superhero in an attempt to feel less helpless. One family draws graffiti art to cheer up a neighbor, while another one comes together over a jigsaw puzzle when theres not much else to do. A whimsical character in these comics embodies the very idea of comics forging community: the Japanese mythical creature Amabie says, Drawing my picture and sharing it makes people feel connected with each other. A global connection through art! This kind of connection inspires hope.

And there is hope in these pages. In the figure of Amabie and in all the ways these comics show people managing to stay connected during lockdown, keeping businesses open, keeping kids busy, maintaining rituals, starting families, supporting one anotherin short, responding in very creative ways to a world out of control. I want to thank the artists, writers, letterers, colorists, and translator who donated their time and talents to this project. We will be donating a portion of the proceeds from the sale of this book to the Book Industry Charitable Foundation in support of bookstores and their employees whose livelihoods have been upended by COVID-19. Thanks also to Rich Johnson and my wonderful colleagues at Penn State University Press for the unfailing expertise and care they brought to the publication of this book. Finally, I want to thank Susan Squier and my graphic medicine friends, who have drawn me along this path with them, on this remarkable voyage of discovery through comics.

Next page