Text Sheena C. Howard 2017

Cover design by John Jennings

Edited by Larisa Hohenboken

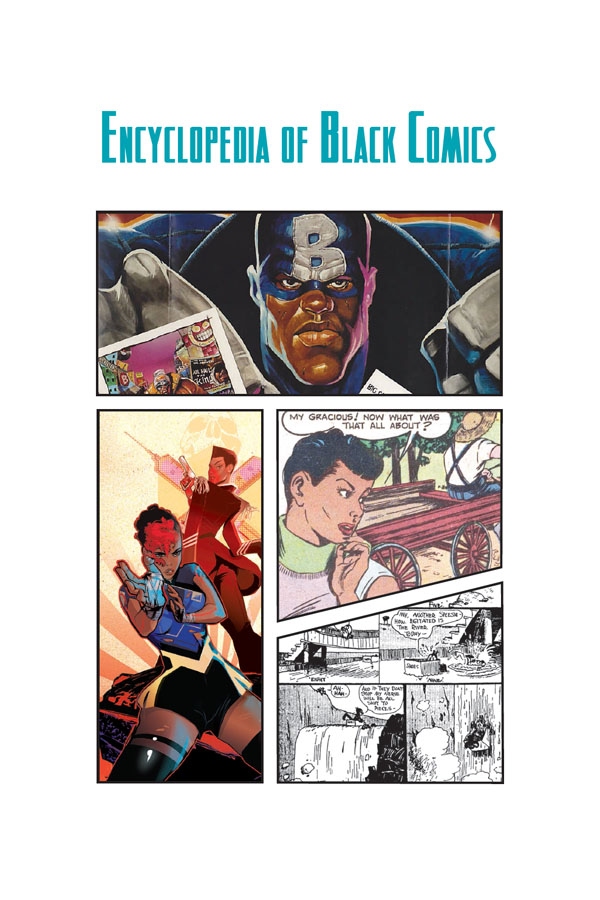

Image credits: title page (Afua Richardson [left], Professor W. Foster [top], Nancy Goldstein [right], Comic Strip Archives [bottom]).

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Howard, Sheena C., author. | Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., writer of foreword. | Priest, Christopher J. (Christopher James), 1961- writer of afterword.

Title: Encyclopedia of black comics / Sheena Howard ; foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. ; afterword by Christopher Priest.

Description: Golden, CO : Fulcrum Publishing, [2017] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017027581 | ISBN 9781682751015 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Comic books, strips, etc.--Encyclopedias. | American literature--African American authors--Encyclopedias. | African American cartoonists--Encyclopedias. | African Americans in literature--Encyclopedias. | African Americans in popular culture--Encyclopedias. | Graphic novelsUnited StatesHistory and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Comics & Graphic Novels. | LITERARY COLLECTIONS / American / African American. | REFERENCE / Encyclopedias.

Classification: LCC PN6707 .H69 2017 | DDC 741.5/03 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017027581

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Fulcrum Publishing

4690 Table Mountain Dr., Ste. 100

Golden, CO 80403

800-992-2908 303-277-1623

https://fulcrum.ipgbookstore.com

C ONTENTS

F OREWORD

by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

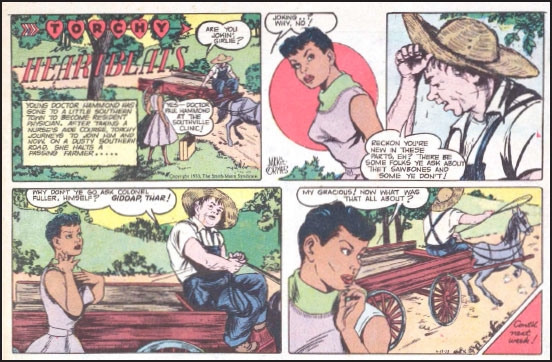

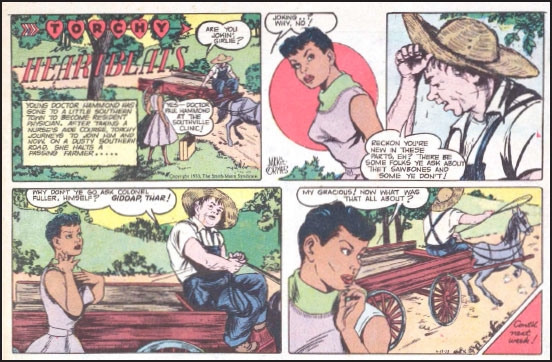

Pam Griers star-turn in the 1974 Blaxploitation classic, Foxy Brown, is a cultural touchstone, as significant for Griers badass performance as it is for her fashionable embrace of the Afro. But who still remembers Torchy Brown? A style icon in her own way, Torchy Brown, for those of you who like to win at trivia, was the star of Dixie to Harlem, the first comic strip by a Black woman about a Black woman. Long before Foxy Brown went out seeking vengeance in the Black Power era, Torchys Depression-era rags-to-riches story featured a runaway from Mississippi who finds renown in Harlems legendary Cotton Club alongside Bill Bojangles Robinson, Cab Calloway, and the one and only Josephine Baker, who calls Torchy My baby!

Torchy Brown image courtesy of Nancy Goldstein

Torchy first appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1937. She flowed out of the pen of Zelda Mavin Jackson, known as Jackie Ormes, a twenty-six-year-old woman from Monongahela, Pennsylvania, who taught herself to draw by copying comics out of the newspaper. Like Torchy, Ormes was making her way in the North as part of a pioneering generation of professional African American women in politics, education, and entertainment. And the struggle they waged to represent and uplift the race was anything but easy, crowded out as it often was by decades of negative Jim and Jane Crow stereotyping.

How do I know about Ormes? She is a highlight in the ever-more fascinating pages of Sheena C. Howards Encyclopedia of Black Comics, contained within the covers of this book. One of its defining features is the fact that fully one-third of the 106 biographies Howard has chosen for her pathbreaking volume are on African American women artists, publishers, comic convention founders, and other leading figures in the Black comics industry. In other words, Ormes is in good company here, illustrating the astonishing power of comic books and graphic novels to reflect the diversity that defines the Black American experience. The biographies of these artists, from the early twentieth century to today, also offer us a unique compass for charting the startling changes weve seen in that same span in African American culture and society and American race relations as a whole.

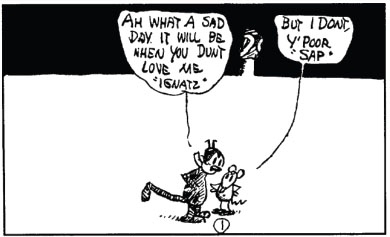

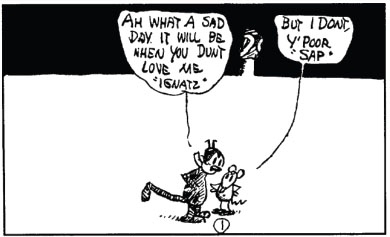

Krazy Kat image courtesy of Comic Strip Library

Without giving too much away, the first major Black, or colored, cartoonist canonized in Howards Encyclopedia is New Orleanian George Herriman. At least, thats how his 1880 birth certificate defined him, though when he moved to New York to ply his trade, he began identifying himself as French or Greek, the latter being his nickname, Greek Herriman, the genius behind the smash comic strip, Krazy Kat. The first self-identified Black cartoonists, emerging in the 1920s and 1930s, were Wilbert Holloway and Jay Jackson, who attended art colleges and wrote for major Black newspapers. In the Chicago Defender, Jacksons As Others See It lampooned the manners and mores of established Black urban dwellers as well as those whod only arrived from the rural South by way of the Great Migration. Holloways Sunny Boy Sam appeared in the Courier from 1928 until his death in 1969, and along the way he earned awards for his cartoons attacking lynching and the Ku Klux Klan, and for opposing Italys invasion of Ethiopia before the start of World War II. As memorable, Holloway designed the indelible Double V logo, which the Courier promoted to rally African Americans to press for victory at home and abroad during the war. Another founding Black cartoonist was Ollie Harrington, the son of an African American construction worker and a Jewish Hungarian mother in the South Bronx. The main cartoonist for the New York Amsterdam News in the 1930s, Harrington innovated Dark Laughter, later taken up by other Black papers, which was uncompromising in its vociferous critique of American racism. Harrington, who reported on the experiences of Black soldiers in Italy and North Africa for the US State Department, nevertheless found himself being investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (or HUAC) for his radicalism, to the point that he eventually settled in communist East Germany in the early 1960s.

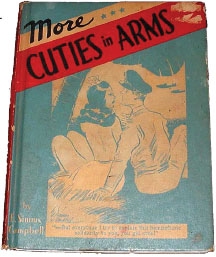

The first self-identifying Black cartoonist to be featured in mainstream publications was E. Simms Campbell, who landed in New York at the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance. Among his numerous achievements: Campbell drew a Night Club Map of Harlem, illustrated poems by Sterling Brown, and, with luminaries Arna Bontemps and Langston Hughes, produced an illustrated childrens book, Popo and Fifina: Children of Haiti (1932). From there, he began placing cartoons in Esquire, The New Yorker, and other trendsetting publications even Playboy, home to that other influential Black cartoonist Buck Browns risqu Granny character. Amazingly, few readers ever knew Campbell was Black.

More Cuties in Arms photo courtesy of Professor W. Foster

However haltingly, opportunities for African American cartoonists expanded beyond the Black press in the years after World War II. For example, Orrin Evans created the first Black comic book,

Next page