LINCOLN

on

RACE & SLAVERY

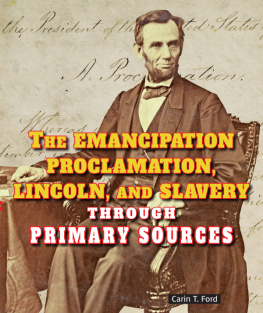

The image placed here in the print

version has been intentionally omitted

Abraham Lincoln (18091865), taken at Mathew Bradys Studio, New York City, on February 28, 1860, a day after the Cooper Institute address.

LINCOLN

on

RACE & SLAVERY

Edited and introduced by

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Coedited by Donald Yacovone

Copyright 2009 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865.

Lincoln on race and slavery / edited and introduced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. ; coedited by Donald Yacovone.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14234-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Views on slavery. 2. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Political and social views. 3. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Relations with African Americans. 4. SlaveryUnited StatesHistory19th centurySources. 5. SlavesEmancipationUnited StatesSources. 6. United StatesRace relationsHistory19th centurySources. I. Gates, Henry Louis. II. Yacovone, Donald. III. Title.

E457.2.L744 2009

973.7092dc22

2008049960

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in PUP Monticello and Gloucester MT Extracondensed Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Designed by Isabella D. Palowitch, Artisa, LLC

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

For

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham

and

in Memory of

George M. Fredrickson

CONTENTS

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Donald Yacovone for bringing to bear his considerable expertise on the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln in the preparation of the headnotes that preface the selections of Lincolns writings. In addition, I would like to thank John Sellers, Sheldon Cheek, Tom Wolejko, Julie Wolf, Aditya Basheer, and Joyce Clifford for their research assistance. Allen Guelzo, John Stauffer, Ira Berlin, Philip Kunhardt, Peter Kunhardt, Ted Widmer, Donald Yacovone, David Herbert Donald, James McPherson, and Tina Bennett read several drafts of my introduction, and provided quite helpful criticisms and suggestions.

This book grew out of my research for my PBS documentary, Looking for Lincoln, which marks the bicentennial of Abraham Lincolns birth. I would like to thank Doris Kearns Goodwin, and my fellow executive producers, William Grant, Peter Kunhardt, and Dyllan McGee, and my producers, Barak Goodman, John Maggio, and Muriel Soenens, for helping me to understand my own relationship to Lincoln and Lincolns relationship to our times.

I would also like to thank my agent, Tina Bennett, and my editor at Princeton University Press, Hanne Winarsky, for their support of the publication of this book to coincide with the airing of our documentary series. Lauren Lepow expertly edited my introduction, helping me to understand what it was I was trying to say.

The texts of Lincolns writings and speeches are taken from The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln [CW], edited by Roy P. Basler, published under the auspices of the Abraham Lincoln Association (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 19531990), available online at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln .

Abraham Lincoln on Race and Slavery

What I would most desire would be the separation of the white and black races....

SPEECH AT SPRINGFIELD, JULY 17, 1858

Certainly the negro is not our equal in colorperhaps not in many other respects; still, in the right to put into his mouth the bread that his own hands have earned, he is the equal of every other man, white or black.

SPEECH AT SPRINGFIELD, JULY 17, 1858

... I have expressly disclaimed all intention to bring about social and political equality between the white and black races, and, in all the rest, I have done the same thing by clear implication.

I have made it equally plain that I think the negro is included in the word men used in the Declaration of Independence....

But it does not follow that social and political equality between whites and blacks, must be incorporated, because slavery must not. The declaration [of Independence] does not so require.

LETTER TO JAMES N. BROWN, OCTOBER 18, 1858

They say that between the nigger and the crocodile they go for the nigger. The proportion, therefore, is, that as the crocodile to the nigger so is the nigger to the white man.

SPEECH AT HARTFORD, MARCH 5, 1860

I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel.

LETTER TO ALBERT G. HODGES, APRIL 4, 1864

But what was A. Lincoln to the colored people or they to him? As compared with the long line of his predecessors, many of whom were merely the facile and servile instruments of the slave power, Abraham Lincoln, while unsurpassed in his devotion to the welfare of the white race, was also in a sense hitherto without example, emphatically, the black mans President: the first to show any respect for their rights as men.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, 1865

... Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man. He was preeminently the white mans President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.... You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his step-children, children by adoption, children by force of circumstances and necessity.

I have said that President Lincoln was a white man, and shared the prejudices common to his countrymen towards the colored race.... Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, 1876

All throughout his debates with Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln never allowed himself to be without a thin black leather notebook that he had converted into a scrapbook, preparation for the war of words in which he and his ardent foe were so passionately and desperately engaged. It served Lincoln almost as a cheat sheet, a ready-reference tool to which he could conveniently revert for facts and figures, opinions from editorials and letters to the editor, and clips from newspaper stories about all those pressing issues of the day over which he and Douglas so thoughtfully, if feverishly, were debating. The notebook, now housed in the Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congresssix inches high, three and three-quarters inches wide, an inch thick, its covers made of hardboardwas small enough to slip into his coat pocket, discreet enough for Lincoln to consult on the podium while preparing his rebuttals as Douglas redoubled his ferocious attacks. The notebooks metal clasp is broken; it is boxed closely for protection. What a wealth of information about slavery and the most important issues of his day does that slim volume contain! Lincoln knew what he needed to know, or didnt know, to hold his own with Douglas. And he consulted his commonplace book frequently, judging from the wear of the clasp and its well-thumbed, glue-stiff pages.

Next page