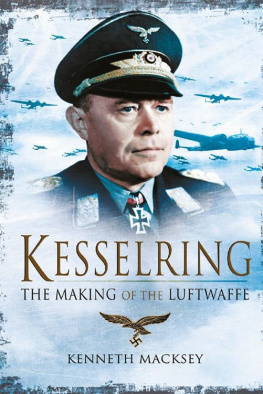

Illustrations from the private collection of the Kesselring family.

This is the biography of a liberal classicist who became one of the most formidable technicians of war known to the twentieth century. It is about a great strategist and organiser who became enmeshed in a pernicious political environment, one who has become side-tracked in terms of public esteem but who has been rated, by a prominent German Chief of Staff, as one of the top three German soldiers with a hold on the troops Erwin Rommel and Heinz Guderian being the others. Although this is not intended to be a history of the campaigns Albert Kesselring fought it must, of course, introduce material and opinions which, up to now, have been obscure, for Kesselring was addicted to modesty, the last man on earth to boast loudly about his considerable accomplishments. And yet it is to him that much credit must be given for laying the foundations of the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe which, by their originality and prowess, won significant initial victories for Adolf Hitler at the beginning of the Second World War. Without his determined contribution, by obstinacy and charm, to a system, these organisations might well have been of average quality. As a result battles that would have been drawn were won and those which might have been lost were drawn. Furthermore, deprived of generalship, Adolf Hitlers most grandiose military schemes might have been squashed at the outset and the long retreat Kesselring was to conduct after 1942 might never have been necessary.

Why then has Kesselring been overshadowed in popularity by men such as Rommel, Guderian, Montgomery, Patton and the other propaganda marvels whose deeds were considerable but who flourished mainly in the upsurge of victories rather than thrived in adversity as did Kesselring for nearly six years? To some extent the answer is to be found, of course, in the realisation that the lives of Hitlers generals remain obscure, even though so many have published their memoirs and historians have benefited by the availability of a mass of relevant material. Disclosures have yet to be made, not all the official histories have been published, and only in the past decade has the diminution of old hostilities made possible a more liberal attitude to the exposure of points of view which were unpublishable in the 1950s. Maybe the sheer volume of material is to blame; there has been too much to digest and, so far as the English-speaking peoples are concerned with regard to German sources, too few interpreters available. Therefore only a minority of the available papers have been translated. In consequence only a discreet lite is as yet apprised of the inside story relating to several important episodes as well as aware of the full range of German sensitivities in those traumatic years. It is information which, after all, is denied to the German people too, let alone to outsiders. The majority of popular books in English about the Germans depend upon only a few familiar sources sources which, in many instances, reflect the immediate post-war biases. Kesselrings story suffers in the classic manner from this repetitive process. Not for him, when he was writing his Memoirs, was there an almost uninhibited access to private references or published works such as his British or American opponents in battle could avail themselves when writing their memoirs. He wrote secretly when he was in prison, cut off from the essential records and frequently under supervision. Moreover, Kesselring and his contemporaries had to take especial care about every word they uttered in case they inadvertently provided the military tribunals with evidence against comrades or themselves. Long after their exclusion from real power, the German commanders had in their hands fuses to detonate several kinds of political bomb, any one of which might harm individuals; damage the state, or wreck the alliances to which their nation aspired to belong. The fact that they imbibed so profound a loyalty to their past calling and considered any kind of adverse publicity repugnant, went almost without mention.

By upbringing, too, Kesselring was suited to operate effectively in the shadow of exuberant personalities, statesmen and politicians who advertised their achievements while he passed over his own immense contributions to their success and took the blame for their errors. The flamboyance of Herman Gring, the immense ability of Erhard Milch and the adulation accorded to Walther Wever, before and after his premature death, hide the truth of the matter that the foundation stone of the Luftwaffe was laid by Kesselring when he was working for Hans von Seeckt and that the structure upon which it was based was fashioned by him. Likewise it is often customary to blame Kesselring for turning Gring, in 1937, against the creation of a strategic bomber force, although it is overlooked that it was he who actually contrived the instrument of air power that became the tactical Luftwaffe which made a vital contribution to the rapid conquest of Poland, Holland, Belgium and France. It is forgotten by some that it was he, controlling the preponderant element of the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain, who so shook the British and he who, in 1941, ruined the Russian air force.

It was Kesselrings fate to assume the role of a Troubleshooter, the unpopular Axeman whose traditional task it is to destroy myths and kill holy cows. Inevitably, therefore, he became the centre of controversy in the public sector when Hitler sent him to restore order out of chaos in the Mediterranean theatre of war at the end of 1941. There he would have to pit his wits against the hierarchy of an Italian ally who was jealously guarding sovereign rights, and against Erwin Rommel, an extrovert whose exploitation of an assiduously won propaganda reputation left no more room for shared glory than did Grings. Naturally the task did not enhance his popularity even if he cared very much that it did. Moreover axemen tend to be sent from one hatchet job to another and this, too, was his experience. So it is all the more astonishing that Kesselring, who won far more battles of intrigue than he lost, besides enjoying notable victories against the foreign enemy, emerged smiling at the end.