Thank you for buying this

Thomas Dunne Books ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my wonderful parents, David and Fela Shapell, who made this book possible.

Benjamin Shapell

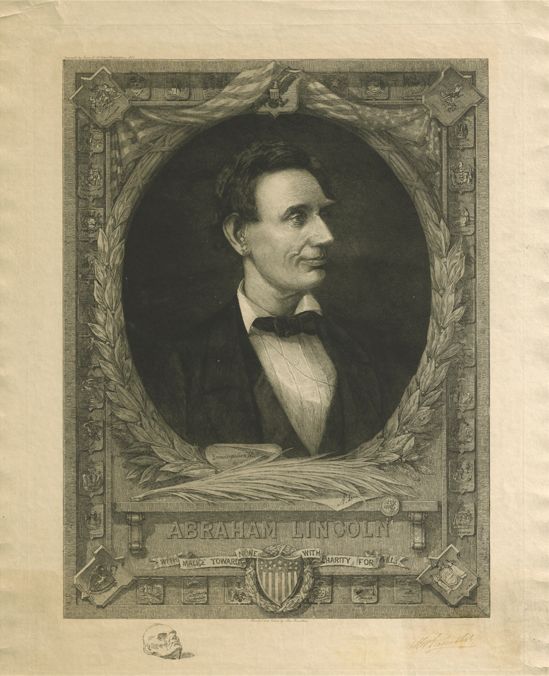

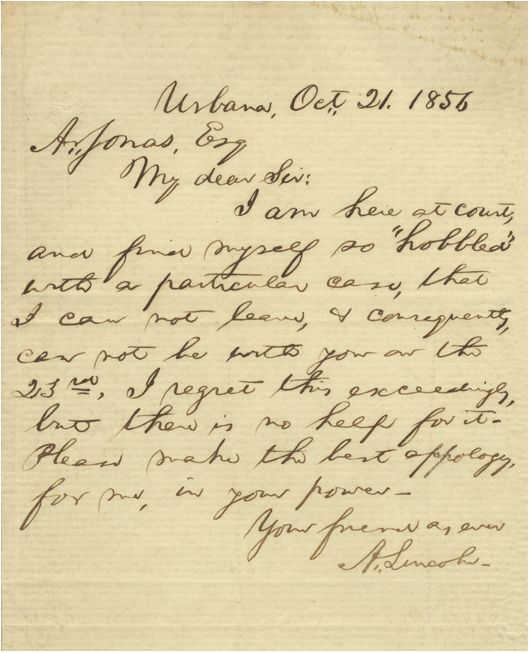

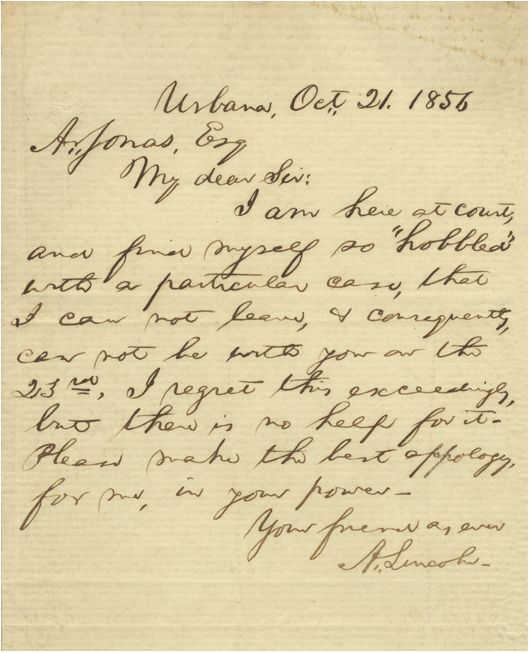

ABRAHAM LINCOLN TO ABRAHAM JONAS, OCTOBER 21, 1856

(see ).

In the field of manuscript collecting, documents are traditionally prized for statements of grand historical fact. While I deeply appreciate those historic letters, I have always, however, been fascinated by the other letters of U.S. presidents; letters with an interesting turn of phrase; letters that express humanity, compassion, modesty, fragility, and irony. Letters one seldom comes across or reads about, such as presidents referring to the White House as a prison, or excoriating other presidents, or lamenting their failure to get reelected, or one, Benjamin Harrison, anxiously looking forward to my discharge and getting out of this House. And then, too, there are ironically prophetic letters, such as President-elect James Garfield, writing, Assassination can no more be guarded against than death by lightning. He would die at the hands of an assassin after only six months in office.

But in the thirty-five years I have been collecting, it is Lincoln, more than anyone else, who has most intently absorbed my interest. He was a self-made man, unschooled but not uneducated, who, with determination, persistence, and firmness of purpose, demonstrated that anyone could rise to, meet, and overcome the challenges of life. Despite the wars heavy toll on him and the country for four long years, the presidency to Lincoln was, as historian Stefen Lorant once wrote, a glorious burden. Lincoln loved the presidency, finding humor where he could amid military and personal setbacks.

In reading through Lincolns vast canon of collected writings, I find myself using the same word fascinating over and over again. His letters and writings are interwoven with jewels, full of wisdom, poetic flair, and marvelous turns of phrase. And while some of these letters are more recognizable than othersthe first and second inaugurals, the Gettysburg Address, or his letter to Grace Bedell about growing a beard, it is still those other lettersthe ones most Americans do not know aboutthat truly impress me. And this too shall pass awayNever fear, Lincoln writes to comfort his campaign manager after losing his 1858 Senate race against Stephen A. Douglas. Or, on the eve of his assured election to the presidency, humbly expressing, I am not a man of great knowledge or learning. Later, Lincoln, sticking to his principles, uses a coarse but effective phrase: Broken eggs can not be mended. I have issued the Emancipation Proclamation and can not retract it.

Many of Lincolns finest words were reserved for the generals who consistently disappointed him: to Major General George Meade, for allowing Robert E. Lees defeated army to escape from Gettysburg (I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lees escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in collection with our other late successes, have ended the war); about General of the Army of the Potomac George McClellans slowness to engage the enemy (If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time). But in other letters to lesser-known generals, an even more complex relationship emerges between the commander in chief and his highest-serving men. Lincoln, regretting the pain he has caused a general by dismissing him, writes: I bear you no ill will; and I regret that I could not have the example without wounding you personally. Or, in a poetic outburst to General Robert Milroy: I would be glad to see Gen. Milroy were it not that I know he wishes to ask for what I have not to give.

Robert Louis Stevenson said: To be wholly devoted to some intellectual exercise is to have succeeded in life. Collecting for me is the passion that constantly infuses my thoughts. It is the tireless, daily adventure of constructing something piece by piece, of drawing strength from history; it is the focus on building something unique and complementary and anchored to themes. I have been privileged to have acquired over the yearsand include in this volumesome truly remarkable examples from Lincolns pen, many formerly held in some of the greatest private collections ever assembled, including those of Oliver Barrett, Phillip Sang, and Malcolm Forbes, as well as new and great discoveries that have emerged from hidden estates or obscure auctions far beyond the beaten path, where their importance was often overlooked.

It is, in fact, those overlooked letters that have formed the genesis of a particular thread in my collection of other Lincoln documents: the barely known relationship between Lincoln and the Jews. One day, thirty years ago, I discovered something amazing: Lincoln knew Jews. Despite the minuscule number of Jews who lived in the Western frontier, as Illinois was then considered, Lincoln still managed to run into Jews and they into him.

I first discovered the Lincoln-and-Jews relationship in an auction catalog when I acquired the hobbled letter (chapter 2), where Lincoln revealingly expresses his frustration, and no doubt embarrassmentat having to defend a wayward nephew accused of thievery. The recipient of the letter was one Abraham Jonas, who, I would come to learn, was a lifelong Jewish friend who supported, campaigned for, and helped engineer Lincolns successful run for the presidency. It is the only known letter from Lincoln to Jonas in private hands, and a great favorite of mine.

As I came across letter after letter in which Lincoln expresses humility, biblical imagery, compassion, and respect for a people and a religion, I was transformed as a collector. Lincoln never wrote, You are one of my most valued friends to anyone, except to his friend and confidant Abe Jonas. And when the latter lay dying in 1864, it was Lincoln who immediately took pen to paper and ordered Jonass son, Charles, a Confederate officer and prisoner of war, paroled for three weeks to visit his dying father.

I am fortunate to include many examples of Lincoln and the Jews in my collection, most of which are included in this book. In my research over the years, I have found dozens more, housed in major public institutions, and all revealing the inescapable truth of the depth and breadth of this relationship and Lincolns interest in the causes important to Jews. It was not during the war that Lincoln met and interacted with Jews for the first time but rather as a young man in Illinois, thirty years before. And over the course of his tragically foreshortened life, as this book shows, he represented Jews, befriended Jews, admired Jews, commissioned Jews, defended Jews, pardoned Jews, consulted with Jews, and extended rights to Jews. His relationships with Jews were not exploitative but warm and genuine, and went further and deeper than those of any previous American president.

Next page