For Jaime

Can I just say? There is no such thing as the best actress. There is no such thing as the greatest living actress. I am in a position where I have secret information, you know, that I know this to be true.

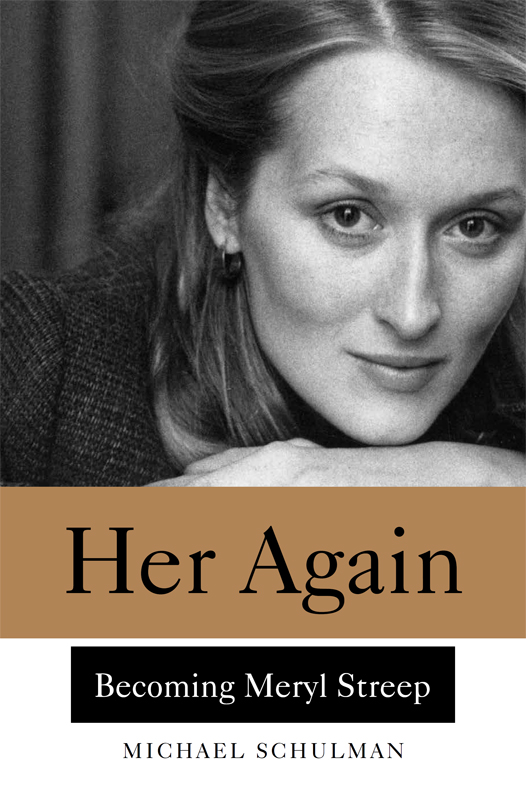

MERYL STREEP, 2009

CONTENTS

Guide

NOT ALL MOVIE STARS are created equal. If you were to trap all of Hollywood in amber and study it, like an ancient ecosystem buried beneath layers of sediment and rock, youd discover a latticework of unspoken hierarchies, thwarted ambitions, and compromises dressed up as career moves. The best time and place to conduct such an archeological survey would undoubtedly be in late winter at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard, where they hand out the Academy Awards.

By now, of course, the Oscars are populated as much by movie stars as by hangers-on: publicists, stylists, red-carpet correspondents, stylists and publicists of red-carpet correspondents. The nominee is like a ships hull supporting a small community of barnacles. Cutting through hordes of photographers and flacks and assistants trying to stay out of the frame, she has endured months of luncheons and screenings and speculation. Now, a trusted handler will lead her through the thicket, into the hall where her fate lies in an envelope.

The 84th Academy Awards are no different. Its February 26, 2012, and the scene outside the Kodak Theatre is a pandemonium of a zillion micromanaged parts. Screaming spectators in bleachers wait on one side of a triumphal arch through which the contenders arrive in choreographed succession. Gelled television personalities await with questions: Are they nervous? Is it their first time here? And whom, in the unsettling parlance, are they wearing? There are established movie stars (Gwyneth Paltrow, in a white Tom Ford cape), newly minted starlets (Emma Stone, in a red Giambattista Valli neck bow bigger than her head). If you care to notice, there are men: Brad Pitt, Tom Hanks, George Clooney. For some reason, theres a nun.

Most of the attention, though, belongs to the women, and the ones nominated for Best Actress bear special scrutiny. Theres Michelle Williams, pixie-like in a sleek red Louis Vuitton dress. Rooney Mara, a punk princess in her white Givenchy gown and forbidding black bangs. Viola Davis, in a lustrous green Vera Wang. And Glenn Close, nominated for Albert Nobbs, looking slyly androgynous in a Zac Posen gown and matching tuxedo jacket.

But its the fifth nominee who will give them all a run for their money, and when she arrives, like a monarch come to greet her subjects, her appearance projects victory.

Meryl Streep is in gold.

Specifically, she is wearing a Lanvin gold lam gown, draped around her frame like a Greek goddesss toga. The accessories are just as sharp: dangling gold earrings, a mother-of-pearl minaudire, and Salvatore Ferragamo gold lizard sandals. As more than a few observers point out, she looks not unlike an Oscar herself. One fashion blog asks: Do you agree that this is the best she has ever looked? The implication: not bad for a sixty-three-year-old.

Most of all, the gold number says one thing: Its my year. But is it?

Consider the odds. Yes, she has won two Oscars already, but the last time was in 1983. And while she has been nominated a record-breaking seventeen times, she has also lost a record-breaking fourteen times, putting her firmly in Susan Lucci territory. Meryl Streep is accustomed to losing Oscars.

And consider the movie. No one thinks that The Iron Lady, in which she played a braying Margaret Thatcher, is cinematic genius. While her performance has the trappings of Oscar baithistorical figure, age prosthetics, accent worktheyre the same qualities that have pigeonholed her for decades. In his New York Times review, A. O. Scott put it this way: Stiff legged and slow moving, behind a discreetly applied ton of geriatric makeup, Ms. Streep provides, once again, a technically flawless impersonation that also seems to reveal the inner essence of a well-known person. All nice words, but strung together they carry a whiff of fatigue.

As she drags her husband, Don Gummer, down the red carpet, an entertainment reporter sticks a microphone in her face.

Do you ever get nervous on carpets like this, even though youre such a pro?

Yes, you should feel my heartbut youre not allowed to, she answers dryly.

Do you have any good-luck charms on you? the reporter persists.

Yes, she says, a little impatiently. I have shoes that Ferragamo madebecause he made all of Margaret Thatchers shoes.

Turning to the bleachers, she gives a little shimmy, and the crowd roars with delight. With that, she takes her husbands hand and heads inside.

They wouldnt be the Academy Awards if they werent endless. Before she can find out if shes this years Best Actress, a number of formalities will have to be endured. Billy Crystal will do his shtick. (Nothing can take the sting out of the worlds economic problems like watching millionaires present each other with golden statues.) Christopher Plummer, at eighty-two, will become the oldest person to be named Best Supporting Actor. (When I emerged from my mothers womb I was already rehearsing my Academy speech.) Cirque du Soleil will perform an acrobatic tribute to the magic of cinema.

Finally, Colin Firth comes out to present the award for Best Actress. As he recites the names of the nominees, she takes deep, fortifying breaths, her gold earrings trembling above her shoulders. A short clip plays of Thatcher scolding an American dignitary (Shall I be mother? Tea, Al?), then Firth opens the envelope and grins.

And the Oscar goes to Meryl Streep.

THE MERYL STREEP acceptance speech is an art form unto itself: at once spontaneous and scripted, humble and haughty, grateful and blas. Of course, the fact that there are so many of them is part of the joke. Who but Meryl Streep has won so many prizes that self-deprecating nonchalance has itself become a running gag? By now, it seems as if the title Greatest Living Actress has affixed itself to her about as long as Elizabeth II has been the queen of England. Superlatives stick to her like thumbtacks: she is a god among actors, able to disappear into any character, master any genre, and, Lord knows, nail any accent. Far from fading into the usual post-fifty obsolescence, she has defied Hollywood calculus and reached a career high. No other actress born before 1960 can even get a part unless Meryl passes on it first.

From her breakout roles in the late seventies, she was celebrated for the infinitely shaded brushstrokes of her characterizations. In the eighties, she was the globe-hopping heroine of dramatic epics like Sophies Choice and Out of Africa. The nineties, she insists, were a lull. (She was Oscar-nominated four times.) The year she turned forty, she is keen to point out, she was offered the chance to play three different witches. In 2002, she starred in Spike Jonzes uncategorizable Adaptation. The movie seemed to liberate her from whatever momentary rut she had been in. Suddenly, she could do what she felt like and make it seem like a lark. When she won the Golden Globe the next year, she seemed almost puzzled. Oh, I didnt have anything prepared, she said, running her fingers through sweat-covered bangs, because its been since, like, the Pleistocene era that I won anything.

By 2004, when she won an Emmy for Mike Nicholss television adaptation of Angels in America, her humility had melted into arch overconfidence (There are some days when I myself think Im overrated... but not today). The hitsand the winking acceptance speecheskept coming: a Golden Globe for