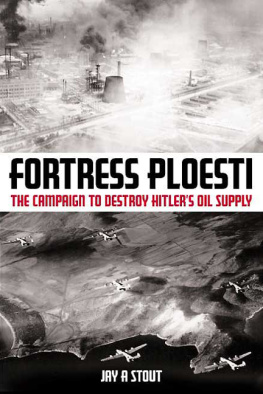

INTO THE FIRE

PLOESTI

THE MOST FATEFUL MISSION OF WORLD WAR II

DUANE SCHULTZ

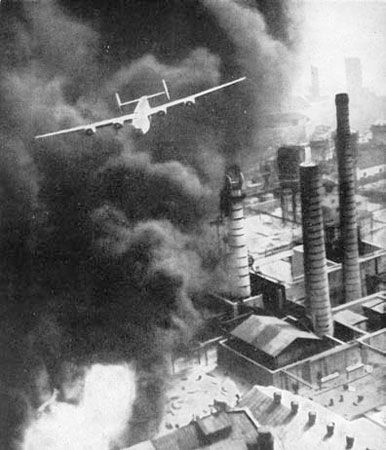

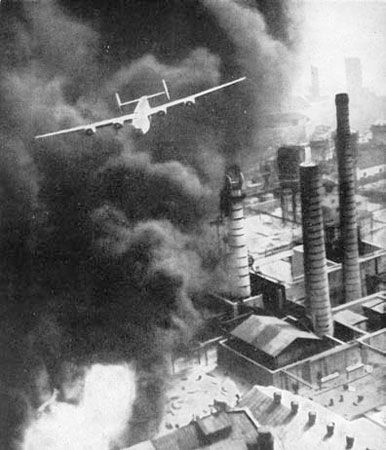

Frontispiece: The Sandman , a B-24D of the 98th Bombardment Group Pyramiders piloted by Lt. Robert W. Sternfels, emerges from the smoke and fires of the bombed Astra-Romana refinery. Taken as a mirror image by an automatic camera in a nearby bomber, it is an iconic photograph of World War II. ( National Archives )

Copyright 2007 Duane Schultz

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Westholme Publishing , LLC

904 Edgewood Road

Yardley, Pennsylvania 19067

Visit our Web site at www.westholmepublishing.com

ISBN: 978-1-59416-505-4

Also available in paperback.

Produced in the United States of America.

It was the worst catastrophe in the history of the Army Air Corps. It wasnt a raid, it was a full-scale battle.

Col. John R. Kane

If you do your job right, it is worth it, even if you lose every plane.

Maj. Gen. Lewis Brereton

We knew it was a disaster and knew that in the flames shooting up from those refineries we might be burned to death. But we went right in.

Lt. Norman Whalen

We were dragged through the mouth of hell.

from a Ploesti Mission debriefing report

CONTENTS

P ROLOGUE: F ROZEN IN T IME

H E LOOKED LIKE C LARK G ABLE , could talk his way into or out of virtually anything, and loved to wear his cowboy boots and pearl-handled revolvers into battle.That was how a Wichita, Kansas, newspaper described 1st Lt. Gilbert B. Hadley when he was buried in 1997, 54 years after he died in the cockpit of his airplane. His boots and pearl-handled revolvers were found in the plane with him, ghostly remnants of another time and place, another world.

Hadley was a member of the Greatest Generation, though probably he would not have thought of himself that way. He was too much of a hell-raiser to have such grand thoughts, certainly not on the day he died in 1943. A flamboyant, rowdy 22-year-old pilot of B-24s from Arkansas City, Kansas, Gib liked to have a good time and to fly his lumbering four-engine bomber like it was a fighter plane.

He joined the army a month before the attack on Pearl Harbor, after completing two years at the local junior college. The family could not afford to send him away to college for a four-year degree, so he did what so many other boys did in his circumstances. He joined the army and was intelligent enough to be accepted for pilot training. The Army Air Corps sent him to flying schools in the area and he took delight in flying low over his house and the homes of friends, seeming to barely miss the rooftops. He attempted the maneuver in single-engine trainers and, later, in B-24s, frightening everybody but himself.

Gib named his plane Hadleys Harem , because he liked to think he had a way with the ladies, and he was also popular with the men who flew with him. He wanted to be one of the guys, not standoffish with the enlisted members of his crew the way some officers were. He chewed us out for saluting him, remembered Staff Sgt. Leroy Newton from Monrovia, California, a 19-year-old at the time of the raid. He let us fly the plane when it was in the air and nothing was happening. He was a budding legend happening right under our feet. There wasnt a thing we wouldnt have done for him.

Sergeant Newton was one of the lucky members of Hadleys Harem . He survived the crash that August evening that took Gib Hadleys life and that of his co-pilot, 22-year-old 2nd Lt. James Lindsay, from Gilmer,Texas. Newton survived the war, and tried not to think much about Hadleys Harem and Gib and the horrors of that terrible day in 1943. He put them out of his mind for 50 years until 1993, when he learned there would be a reunion of the men who flew with him on the famous mission to the Ploesti oil fields of Romania.

Newton went to the 50th reunion, the first such gathering he attended. He was amazed to see a photograph of himself and the six other survivors of Hadleys Harem on a beach in Turkey surrounded by more than a dozen armed men. The picture brought back a flood of memories. He decided to go back, to stand on that beach again and try to find whatever might be left of the plane. The seven of us really owed our lives to him, Newton said of Gib Hadley. Its miraculous he could fly the thing that far. [He and co-pilot Lindsay] gave me a good 50 years on my life, and I feel this was a good payback.

Newton went to Turkey in 1994 and walked the beaches for miles, looking for anything familiar to identify the spot where they came ashore. He knew there was no chance of finding the plane until he found the right beach, but he did not recognize anything. On the last day of his trip a local newspaper reporter interviewed him and published a story about the airplane that had crashed off the coast five decades before and the wounded Americans who had straggled ashore. By the time the article appeared, Newton had returned home, disappointed that his search had been fruitless.

A short time later he received a letter from a Turkish diver who had read about him. The diver wrote that he had discovered the aircraft back in 1972 while filming underwater for a documentary about turtles. Newton was skeptical but decided to go back one more time. The diver took him directly to Hadleys Harem, lying 750 feet offshore in 90 feet of water, broken in three pieces.

The remains of the pilots were in the cockpit, along with a pair of cowboy boots and two pearl-handled revolvers. The bodies were retrieved, positively identified through DNA analyses, and returned to the United States for burial with full military honors.

The B-24s forward section, including the cockpit, was raised, cleaned, and put on display in the Rahmi M. Koc Museum in Istanbul, where it remains as the only survivor of the 177 planes that took off from Benghazi in Northern Africa early on the morning of August 1, 1943.

The other bombers live only in memories, photographs, and the imagination of those of us who look back with wonder, admiration, and gratitude for what those men endured and the terrible price they paid.I tell you, wrote Lt. John McCormick, pilot of Vagabond King, after the mission was over, there wasnt a man among us who will ever be the same.

The battle over Ploestis skies on August 1, 1943, lasted 27 minutes from the time the first bomb was dropped until the last one fell and the surviving planes turned south to head home. Of the 177 Liberators assigned to the mission, 54 had been lost by days end. Only 93 returned to base, and 60 of those were so badly damaged they never flew again. Of the others, 19 landed at Allied airfields such as Cyprus, 7 in Turkey, and 3, including Hadleys Harem , crashed into the sea. The remainder crashed in and around Ploesti.

One of the bombardment group commanders described the mission as the worst catastrophe in the history of the Army Air Corps.A 1999 research report prepared for the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama concluded that the mission to Ploesti was one of the bloodiest and most heroic missions of all time. One of the crewmen who was shot down referred to it as the greatest ground-air battle ever fought.

The casualties were staggering. Of the 1,726 airmen on the mission, 532 were killed, captured, interned, or listed as missing in action. In addition, 440 of those who returned to Benghazi were wounded, some so severely they never returned to active service.

Next page