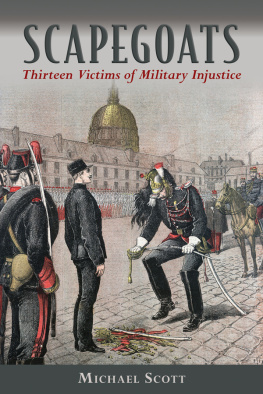

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2015

Text Michael Scott 2013

First published 2013 by Elliott and Thompson Limited

27 John Street, London WC1N 2BX

www.eandtbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Jane Sheppard

Cover photo credit Thinkstock

Print ISBN: 978-1-63220-482-0

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-801-9

Printed in the United States of America

And he shall take the two goats, and present them before the Lord at the door of the tabernacle of the congregation. And Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats; one lot for the Lord, and the other lot for the scapegoat. And Aaron shall bring the goat on which the Lords lot fell, and offer him for a sin offering. But the goat, on which the lot fell to be the scapegoat, shall be presented alive before the Lord, to make atonement with him, and to let him go for a scapegoat into the wilderness.

Leviticus 16:710

By the same author

(With David Rooney)

In Love and War: The Lives of General Sir Harry and Lady Smith

CONTENTS

The Killing of the Prince Imperial

June 1879

The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis

July 1945

Pour encourager les autres

March 1757

Jaccuse

October 1894

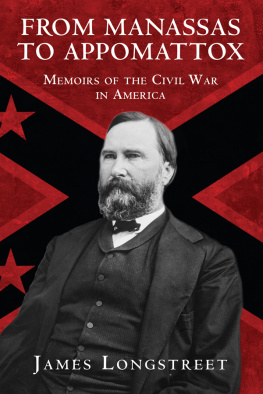

The Old War Horse of Gettysburg

July 1863

Mutiny at taples

October 1917

Disaster of the Sittang Bridge

February 1942

Scapegoat-in-Chief of the Army in South Africa

January 1900

The Battle of Maryang San

October 1951

Scapegoat of the Peninsula

July 1811

Nawab of the Carnatic

August 1754

Atonement

October 1973

Massacre in Rwanda

April 1994

FOREWORD

by Magnus Linklater

General Mike Scott is well placed to write about military scapegoatshe might so easily have become one himself. As commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards in the Falklands War, he was in charge of the assault on the heights of Mount Tumbledown on the night of June 13/14, 1982. It was to be an attack conducted uphill in pitch dark and freezing weather, against experienced Argentine marines, dug into well-defended positions. As General Scott himself concedes in the course of this book, There is an old military maxim that has stood the test of innumerable engagements: the odds favour the defender 3:1.

He would have been well aware of that. He would also have known that, in the hours before the battle, he had twice questioned the orders he had been given, and twice succeeded in getting them changed. If, therefore, things had gone wrong, he would not only have borne the blame, his superiors could, legitimately, have pointed out that he was uniquely responsible for what had ensued. And Tumbledown was a close-run thing. Pinned down under sustained enemy bombardment, with dawn approaching, the battalion might well have had to withdraw, sustaining casualties as it pulled back. Instead it launched a bayonet attack, and, after fierce hand-to-hand fighting, took the last bastion that stood between British troops and the islands capital, Port Stanley.

General Scotts absorbing account of military disasters, and those who were blamed for them, is full of knife-edge engagements like thisand the consequences that flowed from them. They are, in his hands, peculiarly fascinating, because he looks at them with a soldiers eye. He points out how easily, in the fog of war, things might have gone another way, but he can also stand back to analyse why they went wrong, and then distil from them the evidence that points to those who were ultimately responsible.

Scapegoats are usually sought when reputations are at stake, and they tend to be found among the ranks of those who are closest to the action when disaster strikes. Not only are they the ones least capable of answering back, they are there, on the front line, smoking gun in hand, while everyone else runs for cover.

In almost every case that the author examines, however, he finds that the muddled orders, poor communications, failed intelligence, weak strategy or even cowardice of those in overall command were more often responsible for the outcome than those charged with carrying out the ordersthough not always, of course, because General Scott is honest, too, about the failings of soldiers and the circumstances in which they operate. Grand strategy, he points out, may as easily be undermined by the actualities of wartiredness, hunger, fear, lack of sleep, weatheras by poor decision-making or unclear objectives. The fatal blowing up of the bridge at Sittang in Burma in February 1942 might have been avoided if the officer who ordered it had not been suffering from painful sores in his backside. Would Gettysburg have been lost if General Lee, in command of the Confederate forces, had been a bit more outgoing and communicative, and his right-hand man General Longstreet less taciturn on the morning of the attack? The luckless Admiral Byng might not have faced a firing squad for failing to rescue a British stronghold in the Mediterranean if the wind had held up at the crucial moment.

The themes running through this book are as relevant in todays theatres of war as they were in the campaigns and actions that General Scott describes. Time and again we find political or military leaders failing to connect with those whose responsibility it is to deliver the strategy. Chains of command are weak or non-existent; orders are imprecise or muddled; even experienced statesmen and generals, insulated from the realities of the front, can make catastrophic mistakes. And when the worst happens, their instinct is almost always to blame those further down the line.

General Scott is refreshingly brisk in his assessments of character. The governor of Gibraltar in Byngs day is dismissed as a useless soldier... obstructive, deceitful and pathetic. General Sir Redvers Buller, commander-in-chief in the Second Boer War, is a superb major, a mediocre colonel and an abysmally poor general. General Wavell, responsible for the Burma campaign in the Second World War, was not an easy man to understand and interpret, with his interminable silences, while his extraordinary out-of-touch demands and querulous telegrams contributed, in Scotts view, to British setbacks against the Japanese.

He finds among this catalogue of disasters heroes, ill served by their superiors, who battle against great odds and then are blamed for what transpires: Brigadier George Taylor, a straightforward, uncomplicated man with a love of soldiering and a deep respect for his men, who was summarily dismissed in order to placate American allies after winning a stunning victory in Korea; Colonel Charles Bevan, a decent family man who killed himself after being made a scapegoat by Wellington for a setback in the Peninsula War; and Lieutenant General Romo Dallaire, the hero of Rwanda, who attempted to avert a massacre and was abandoned by a supine United Nations which refused to give him the troops he needed.