To Georgia, Connie and Clementine

Copyright 2013 Omnibus Press

This edition 2013 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

EISBN: 978-0-85712-867-6

Cover designed by Fresh Lemon

Picture research by Jacqui Black

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

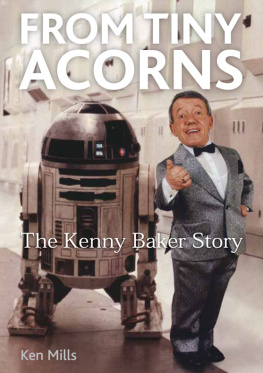

FOREWORD

by Andrew Marshall

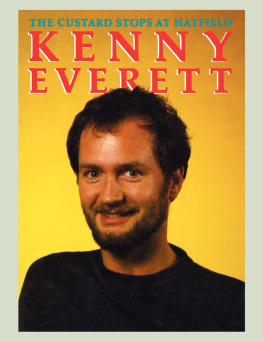

I imagine that for most people who recall Kenny Everett their predominant memory is likely to be of a funny little bearded man in a dress, ostentatiously crossing and re-crossing his legs in a somewhat silly manner. Delightfully warming and chuckle-inducing as this image may be, however, its very far from an illustration of the full range and essence of the remarkable palette of qualities that made the former Maurice Cole of Seaforth, Merseyside, to some of us, a very unusual and beloved figure in British broadcasting.

Imagine BBC Radio in the early sixties: the Light Programme starts each day with a portentous orchestral rendering of Oranges And Lemons by the BBC Northern Heavy Orchestra conducted by the Home Secretary; kitsch childrens dreck is played all Saturday morning by a one-legged man, with the faintly sinister alias of Uncle Mac; Sunday afternoons consist of Semprini Serenade nineteen hours of piano playing by an Italian from Bath building up to Sing Something Simple, a funereal-paced programme of singalong tunes for the gently suicidal.

Into this miasma of Postwar Doldrums stepped the Pirate Radio DJs, and in particular, Kenny.

There had never been anyone on the radio quite like him. He had absolute control of the medium. He was funny. He was cool. He knew The Beatles! And he said just whatever popped into his head at any moment, a quality that was simultaneously stimulating and delightfully dangerous: dangerous for Kenny definitely, as we were to discover; and sometimes dangerous even for us when, for instance, he turned up a Conservative Party Rally and blithely defied what many would have liked him to have said in his continuing devotion to the supremacy of the stream of consciousness.

Oddly, no one ever seems to reflect that one of his later sackings from Radio 1 was for relating a joke that referred to Margaret Thatcher as a part of the female anatomy, illustrating his delightfully complete lack of any kind of political consistency. The first time he was fired, in contrast for following an ingratiating news report that the Minister of Transports wife had just passed her driving test with his quip Bet she pressed a fiver into the examiners hand resulted in the arrival, a week later, of his replacement, Noel Edmonds, handily providing as a bonus a completely legitimate reason for cool listeners to loathe Noel for the rest of his life. Thus nature balances itself.

That unexpected initial sacking was the first major clue as to what made Kenny particularly endearing. He provided a kind of energizing, benevolent, skewed commentary on the world in which he functioned as a Pop-era Puck naughty, friendly, sometimes incisive, sometimes invigoratingly silly, eccentrically distant but always somehow still approachable: an uncontrollable force of disorder that you might nevertheless safely invite to tea with Godfrey Winn, but, on the other hand, the sort of personality that was always going to have what one might call an eventful career.

Like Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, Will Heath-Robinson, Spike Milligan and others, Kenny had the means and talent to create within his chosen medium an entire absurdist world of his own to reside in; but also, like them, he found the actual world a somewhat less amiable land in which to dwell. We have a knack of creating these Lords of Misrule in Britain, perhaps a deep need for them, and the price they pay for being our Beloveds is often a less than satisfactory daily existence than we ourselves would be comfortable with.

It was perhaps inevitable that it was difficult for Kenny to discover a completely suitable long-term partner (although arguably no more difficult than it would be for the average famous person) or set down one completely definitive piece of work (he was far too unfixed a point in the universe for that) or leave behind a tiny Everett or two to continue the mayhem (can you imagine?).

But despite this, and an earlier death than a just Fate might have provided, it isnt at all accurate to think of Kennys life as especially tragic. He was consistently happy in his work, was a kindly and thoughtful man to have as a friend, and when all else failed would always be cheered up by the thought of his apartment being thoroughly steam-cleaned tomorrow. And although he is gone now, there is much to be remembered about him that made us all happy. He interviewed John and Paul on their tour of the USA in the name of Bassetts Jelly Babies. He coined the phrase Naughty Bits. I often reflect that his beautiful singing voice was never commented upon (he was a former choirboy) or his astonishing ability to perform complex fugues in multi-track. And I have to confess, seeing him crossing and re-crossing those legs does still make me laugh. But as you will now discover, with the aid of the astonishing literary varifocals of Caroline and David Stafford, there was a lot more to him than just that

Andrew Marshall wrote 2.4 Children, Whoops Apocalypse and many other hit TV shows. He was also one of the writers on The Kenny Everett Television Show and a close friends of Kennys.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

W e are grateful for the many absorbing hours we spent at the British Library, the British Newspaper Library and the BBC Written Archives Centre, and to the many people gave us far more of their time than we had any right to expect and/or generous permission to quote for their work. They include (in alphabetical order): Keith Ames, Eddie Baines, Bulls Head Bob, Francis Butler, Sue Calf, Annie Challis, Grace Clarke, Michael Coveney, Andrew (The Crosby Herald), Barry Cryer, Yvonne Cureton, Wilfred DeAth, Tessa Ditner, Brian Dooley, Charlie Dore, John Edward, Neil Fleming, Ray Gearing, Roberta Green, Brian Gregg, Jo Gurnett, John Haines, Whispering Bob Harris, Tom Heavey, Christine Kavanagh, Cheryl Kennedy, Tony Kennedy, Richard Kerr, Vicki Lambeth, Bernard Clem Lawson, Peter Leyden, Maisie (The Oldie magazine), Andrew Marshall, Margie Davies Macdonald, David Mallet, Dennis Maughan, Paula McGinley, Nick Micouris, Jon Myer, Trudie Myerscough-Harris, Hilary Oliver, Mike Orme, Harry Parker, Nigel Planer, Richard Porter, Elsie Prescott-Hadwin, David Prest, Ian Rawes, Rowland Rivron, Alexei Sayle, Linda Sayle, Warren Sherman, Keith Skues, Sheila Staefal, Sheila Stanley, Ed Stewpot Stewart, John Sugar, Jeff Walden, Clive Warner, Alison Webb, Mike Webster, Tim Whitnall, Natalie Wright and of course David Barraclough, Jacqui Black, Chris Charlesworth and Charlie Harris of Omnibus Press.

Next page