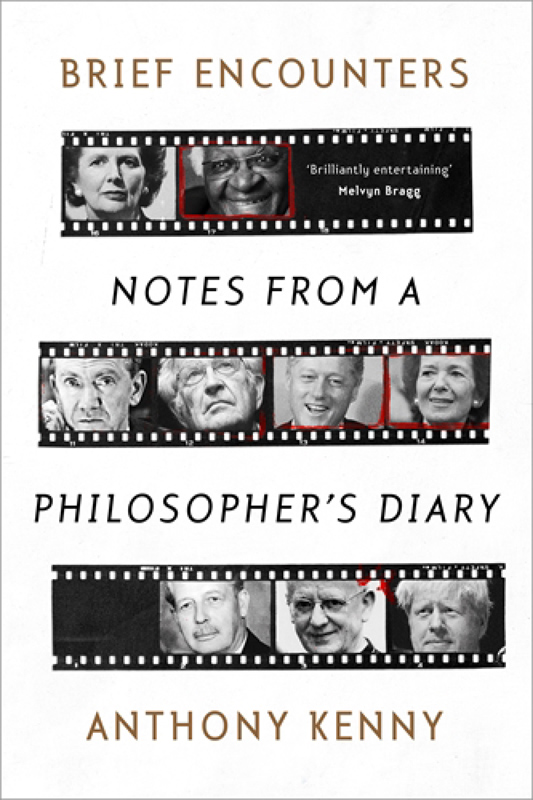

This book is not an autobiography: still less does it attempt to offer brief lives of the subjects of its various chapters. I have had an interesting life, but the interest derives not from anything I have done myself, but from the variety of people I have been lucky enough to know and work with. In succeeding chapters I hope to give an account of my interaction with them. This introductory chapter is intended to give a chronological summary of my own life, so that the reader can tell at what stage and in what capacity I was interacting with the various characters.

I was born in Liverpool on 16 March 1931, the son of John Kenny, an engineer on a steamship engaged in the banana trade, and his wife, Margaret (ne Jones). Sadly, I have only fragmentary memories of my father. Not only was he continually at sea, but by the time I was two years old my parents marriage had broken up, and my mother and I lived in the house of my widowed grandmother. My fathers ship, Sulaco , was enrolled in the Merchant Navy, and in October 1940 it was sunk by a German submarine with the loss of almost the entire crew.

My schooling was strictly ecclesiastical. For two years I was educated by nuns of the order of La Sagesse in a Liverpool suburb, and for the next five I studied at the Jesuit school of Saint Francis Xavier in the centre of the city. My education was interrupted by periods of evacuation to the countryside to avoid the German bombs which were falling on Merseyside. At the age of 12, I entered Upholland college, the junior seminary of the Liverpool archdiocese, and remained there for six years. From there I moved to the English College in Rome to complete training for the priesthood. I was ordained a priest in 1955.

After ordination I undertook graduate studies in theology, writing a dissertation on religious language, which involved one year of study in Rome and one in Oxford. The year in Oxford expanded into two to allow me to write simultaneously a philosophical dissertation, which became my first published book, Action, Emotion and Will (1963) which, in a second edition, is still in print.

There followed four years as a curate in Liverpool, during which I became certain that my ordination had been a terrible mistake. Already, as a seminarian, I had felt doubts about aspects of the Catholic faith, but I stifled them. But before the four years were up, I had ceased to accept many of the doctrines that it was a priests obligation to believe and teach. I decided to leave the priesthood and was laicized by Pope Paul VI in 1963. A year or two later I met my future wife, Nancy Caroline Gayley of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and we were married in 1966. We have two sons: Robert, born in 1968, and Charles, born in 1970.

Since 1964, my life has centred upon Oxford University. My academic discipline, once I had left the Church, was philosophy. At Oxford, philosophy is taught as one of several groups of disciplines making up BA courses known as honour schools. The two principal ones were known as Greats, in which philosophy was combined with ancient history and literature, and PPE, in which it combined with politics and economics. After two terms in a temporary post shared between Trinity and Exeter colleges, I was elected to a tutorial fellowship at Balliol. Tutorial fellows of colleges form the backbone of Oxfords academic staff. As a member of a colleges governing body, a fellow, however junior, shares, on equal terms, the administration of an ancient charitable corporation. If the fellow is also a tutor, he or she is responsible perhaps with one or two colleagues for the education of undergraduates in his or her own particular discipline.

When appointed to Balliol I was, as a matter of routine, made a Master of Arts of the university. This made me a member of Congregation, the assembly of all MAs engaged in teaching or administration in Oxford. Congregation was the town meeting of dons; in constitutional terms, it was the sovereign body of the university. Most of the universitys executive business was conducted by a much smaller elected body, called Hebdomadal Council; but any proposed change in the university statutes, or major item of business, had to be submitted for approval to Congregation, which met several times each term.

An autobiography of my Oxford days would have for its most accurate title, A Life in Committees . For the first part of my career, these would be college committees, and in the latter part, university committees. In the course of time I served on most college committees, but my main administrative experience was as senior tutor for four years. The senior tutor was responsible for the academic administration of the college, and for arranging and monitoring the tutorial teaching of junior members.

I had not been senior tutor for long when, in April 1976, I was placed on the search committee to seek a new Master to replace Christopher Hill, who was retiring in 1978. After a year considering various outside candidates, the Balliol fellows decided that they wanted to elect a candidate from within the fellowship. At this point I withdrew from the search committee, and was myself chosen as Master in the spring of 1978. I took office in October of that year.

The Master of a college has little statutory authority. He or she chairs the governing body, and has a casting vote, but the only power he or she has is the power to persuade. In the course of a dozen years as Master I often had to cheerfully accept being voted down. In the last week of every eight-week term, the Master has to conduct an operation known as handshaking. Undergraduates come, one by one, to sit at the dining table in the lodgings and listen to their subject tutors as they report to the Master on the terms work. Handshaking gives a head of house an opportunity to check up on the tutors as well as undergraduates.

In an autobiography, I described the job of a Master in these words:

A Master of Balliol has to relate to the three different estates of the college: the junior members, the senior members, and the old members. It is one of his duties to try to make each of these groups understand and be ready to learn from the others. I spent much of my time trying to explain to undergraduates why dons think as they do and to dons why undergraduates behave as they do, and to alumni why the college today is not what it was when they were in the heyday of their youth. If I were asked to put the duties of a Master in a nutshell I would say that it is to be a peacemaker: to hold the ring between senior and junior members, to persuade one fellow that he has not been impardonably insulted by another, and to reconcile old members to the college of the present day.

A job description today, rather than in the heyday of student revolution, would place less emphasis on peacekeeping between junior and senior members. It would, however, lay stress on something not then mentioned: the raising of funds for the college. I did in fact, as Master, head a septcentenary appeal; but it took less than two years, and for most of my tenure I was allowed to direct my energies elsewhere.

Being Master gave me an opportunity to meet Balliol alumni who had gone into various walks of life: several of them figure in later chapters. Members from past years would reassemble from time to time in gaudies, and sometimes they would come to take a look at the college and decide whether to encourage their children to apply to it. One such visit was made by William Rees-Mogg, then the editor of The Times . He took one look at the college, and one look at me, and decided to send his son Jacob to Trinity.

Next page