This edition first published 2019

2019 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Edition History

First Edition (Wiley Blackwell, 1998); Second Edition (Wiley Blackwell, 2006)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Anthony Kenny to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Office(s)

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kenny, Anthony, 1931- author.

Title: An illustrated brief history of western philosophy, 20th anniversary edition / Sir Anthony Kenny, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Description: 3rd Edition. | Hoboken : Wiley, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018029651 (print) | LCCN 2018031024 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119531173 (Adobe PDF) | ISBN 9781119452805 (ePub) | ISBN 9781119452799 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: PhilosophyHistory.

Classification: LCC B72 (ebook) | LCC B72 .K44 2018 (print) | DDC 190dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018029651

Cover image: Frontispiece of Opera, vol.II, by Aristotle.

Venice: A. Torresanus, 1483. PML 21195. New York, The Pierpont Morgan Library.

2018. Photo The Morgan Library & Museum / Art Resource, NY / Scala, Florence

Cover design by Wiley

Preface

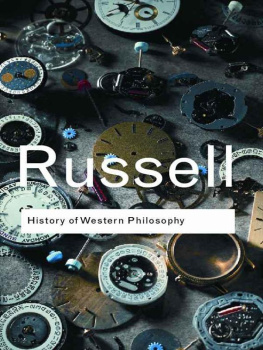

In the year 1946 Bertrand Russell wrote a one-volume History of Western Philosophy, which is still in demand. When it was suggested to me that I might write a modern equivalent, I was at first daunted by the challenge. Russell was one of the greatest philosophers of the century, and he won a Nobel Prize for Literature: how could anyone venture to compete? However, the book is not generally regarded as one of Russell's best, and he is notoriously unfair to some of the greatest philosophers of the past, such as Aristotle and Kant. Moreover, he operated with assumptions about the nature of philosophy and philosophical method which would be questioned by most philosophers at the present time. There does indeed seem to be room for a book which would offer a comprehensive overview of the history of the subject from a contemporary philosophical viewpoint.

Russell's book, however inaccurate in detail, is entertaining and stimulating and it has given many people their first taste of the excitement of philosophy. I aim in this book to reach the same audience as Russell: I write for the general educated reader, who has no special philosophical training, and who wishes to learn the contribution that philosophy has made to the culture we live in. I have tried to avoid using any philosophical terms without explaining them when they first appear. The dialogues of Plato offer a model here: Plato was able to make philosophical points without using any technical vocabulary, because none existed when he wrote. For this reason, among others, I have treated several of his dialogues at some length in the second and third chapters of the book.

The quality of Russell's writing which I have been at most pains to imitate is the clarity and vigour of his style. (He once wrote that his own models as prose writers were Baedeker and John Milton.) A reader new to philosophy is bound to find some parts of this book difficult to follow.

It is not possible to explain in advance what philosophy is about. The best way to learn philosophy is to read the works of great philosophers. This book is meant to show the reader what topics have interested philosophers and what methods they have used to address them. By themselves, summaries of philosophical doctrines are of little use: a reader is cheated if merely told a philosopher's conclusions without an indication of the methods by which they were reached. For this reason I do my best to present, and criticize, the reasoning used by philosophers in support of their theses. I mean no disrespect by engaging thus in argument with the great minds of the past. That is the way to take a philosopher seriously: not to parrot his text, but to battle with it, and learn from its strengths and weaknesses.

Philosophy is simultaneously the most exciting and the most frustrating of subjects. Philosophy is exciting because it is the broadest of all disciplines, exploring the basic concepts which run through all our talking and thinking on any topic whatever. Moreover, it can be undertaken without any special preliminary training or instruction. But philosophy is also frustrating, because, unlike scientific or historical disciplines, it gives no new information about nature or society. Philosophy aims to provide not knowledge, but understanding; and its history shows how difficult it has been, even for the very greatest minds, to develop a complete and coherent vision. It can be said without exaggeration that no human being has yet succeeded in reaching a complete and coherent understanding even of the language we use to think our simplest thoughts.

Philosophy is neither science nor religion, though historically it has been entwined with both. I have tried to bring out how in many areas philosophical thought grew out of religious reflection and grew into empirical science. Many issues which were treated by great past philosophers would nowadays no longer count as philosophical. Accordingly, I have concentrated on those areas of their endeavour which would still be regarded as philosophical today, such as ethics, metaphysics, and the philosophy of mind.

Next page