For my mother, Kathleen, and the other Fab Four: J, K, L & M

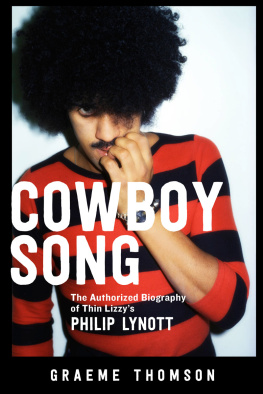

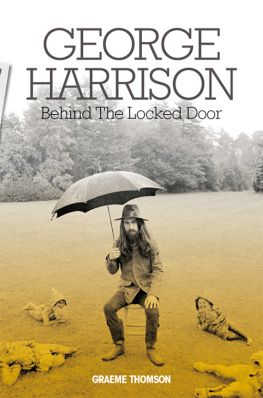

Text Graeme Thomson

Copyright 2013 Omnibus Press

This edition 2013 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

EISBN: 978-0-85712-858-4

Cover designed by Fresh Lemon

Picture research by Jacqui Black

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Contents

Prologue

Be Here Now

New York, August 1, 1971

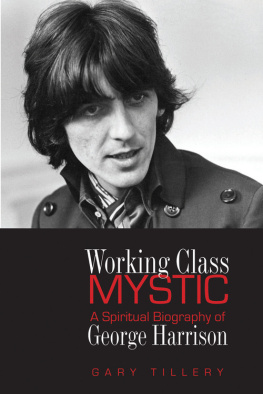

I t was 40 years ago today give or take a week. It is July 2011 and Ravi Shankar is remembering the Concert For Bangladesh. Ninety-one-years-old, frail but sharp and magnificently silver-bearded, his recollections are fresh and clear as mountain air. It became something so big that I couldnt believe it, says Indias greatest classical musician of the modern age. It was, he smiles, a momentous thing.

Few would argue. Momentous not just musically and culturally though it was both; and momentous not just for the thousands of refugees and war children whose plight received worldwide recognition and who, later, perhaps gained some small crumb of material comfort thanks to the music played that day. It was also a momentous landmark for the man Shankar calls my brother, my friend and my son, all together.

Rock musics first en masse act of philanthropy was the symbolic pinnacle of George Harrisons career solo or otherwise. The two concerts, staged at Madison Square Garden on the afternoon and evening of Sunday, August 1, 1971, and starring Harrison, Shankar, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Leon Russell, Billy Preston and Ringo Starr, were a perfect synthesis of everything the former Beatle stood for at the moment of his greatest potency. Through its founding humanitarian impulse; its daring attempt at cultural cross-fertilisation; its undercurrent of benevolent spiritualism, and its genuine and crusading desire to open hearts, eyes and minds to the East, the concert both embraced Harrisons personal passions and sought to perpetuate, without any great cosmic fuss, the wider idealism of the Sixties. And then there was the music, a bubbling brew which further reflected Harrisons expansive outlook, placing the sounds of the sitar, sarod, tabla and tamboura alongside a kinetic mix of rock, blues, soul, folk, pop, gospel and R&B. In so doing, the Concert For Bangladesh was a flesh-and-blood incarnation of the soulful quest for spiritual enlightenment and uplift that had made his debut solo album, All Things Must Pass, such a fiercely impressive statement the previous year. On record, and now on stage, Harrison seemed like a new breed of emotionally evolved rock star for a new era.

Such a thing would have seemed highly unlikely even 12 months earlier. Harrison was historically the Beatle with the lowest profile. He was never The Quiet One that was a shallow, simplistic label but he was the least flashy, the least brash, the one who was drawn least to the spotlight. After the band split officially in April 1970 there was no shortage of observers who half expected him to disappear to an ashram and never return. Instead, in August 1971 he was enjoying by far his most fertile period as a musician. A triple album, All Things Must Pass had been released at the end of 1970 and had stayed at number one in the UK and US for close to two months. At the same time, its lead single, My Sweet Lord, was also number one on both sides of the Atlantic. It would become the best-selling song of 1971 in Great Britain, but sales and statistics can only tell you so much. These were colossal records, charged with a powerful spiritual current which connected to the most generously idealistic impulses held over from the late Sixties.

Look more closely and Harrisons quiet rise to prominence makes sense. He was the Beatle who, during the bands lifespan, travelled furthest from his prosaic origins and became the first to seriously question and challenge their gestalt relationship. All four men experienced a highly accelerated evolution Fab years were akin to dog years: one equalled four or five of the human equivalent but as the youngest and initially the least worldly, Harrison went on the longest journey of all The Beatles, says Bill Harry, founder of the influential early Sixties Liverpool pop zine Mersey Beat and a close friend of Harrison and the other members in their formative years. He was the one who became more stretched than the others. By the late Sixties he was stretched tight, still only in his mid-twenties and travelling fast, at last acutely aware of his potential and intent on fulfilling it. Harrison ended the decade on a roll. Having recorded two of his greatest songs, Here Comes The Sun and Something during The Beatles final sessions for Abbey Road, he was the only band member who could reasonably be said to have walked away from the group with his songwriting and profile in the ascendancy. During the dark days of 1970 and 1971 he seemed to keep his head and largely his own counsel while Lennon and McCartney tore strips off of each other in public. He was the only Beatle who, in the general public perception at least, entered the Seventies still swaddled in their unique force field of idealism, optimism and innate warmth.

For a brief spell, it seemed easier for Harrison to be a Beatle outside of the band than in it. That would change, but for now their legacy gave him kudos as a solo artist without imposing any of the creative restrictions hed had to endure over the previous decade. I do think he was overshadowed by John and Paul in the band, but he really came into his own when they split up, says Glyn Johns, who all but produced Let It Be in 1969 and worked with Harrison on several Apple albums. I thought the way he handled his career and himself at that moment was astonishing, and I came to be an enormous fan. He certainly held his head as high as any of them as a solo artist after The Beatles broke up. He cast his net outside of the norm and the comfort zone and had huge success, and more power to him.

The impulse behind the Concert For Bangladesh was far too urgent for it to be a mere coronation, but none the less it became the crowning moment of a remarkable 12 months. He certainly looked the part: heavily bearded, extravagantly maned, emanating grace. Dressed in a simple woollen shirt and waistcoat during his introductory speech, Harrison looked like a noble toiler of the soil plucked from some work of late 19th-century Russian literature; later, scaled-up a little for the performance, he was brilliant in a white suit, benevolently Messianic for those who looked for their rock stars and ex-Beatles to be such a thing, and plenty did.

Crucially, the music was rich and raggedly powerful. He played three of his most famous Beatles songs, recorded in either 1968 or 1969: Something, While My Guitar Gently Weeps and Here Comes The Sun, downsized to a humble folk strum. By doing so he acknowledged The Beatles weighty legacy with a light touch, incorporating his past into the wider context of his own solo work without being suffocated by it. He would struggle to pull off that particular trick again, but for now these songs simply felt like part of him, merging seamlessly with his new solo music.

Next page