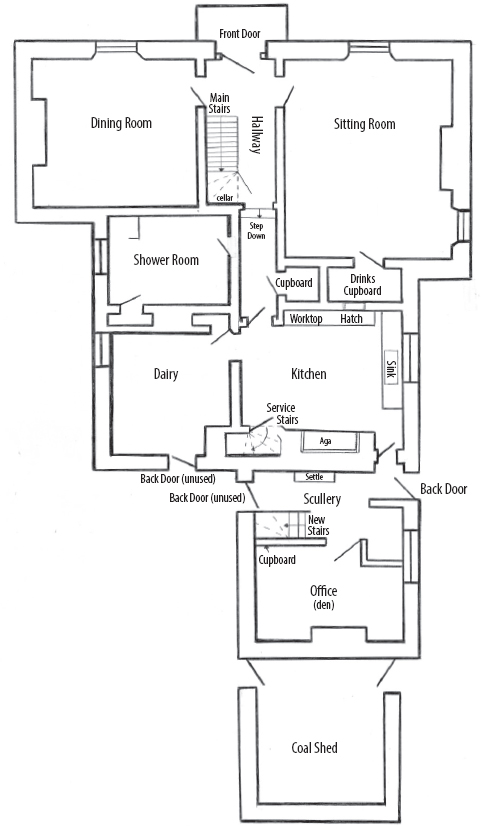

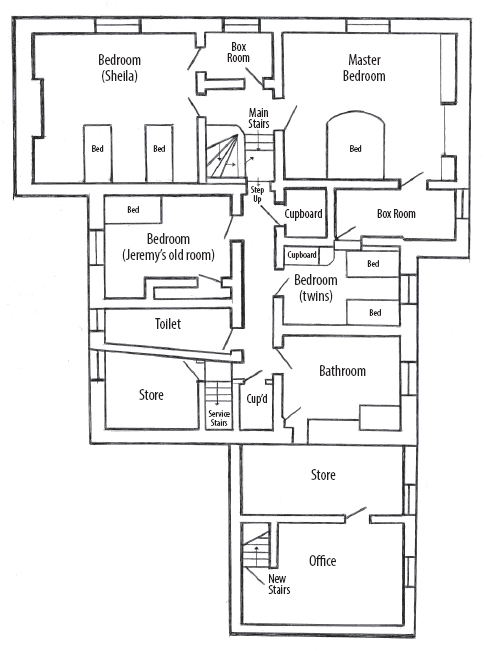

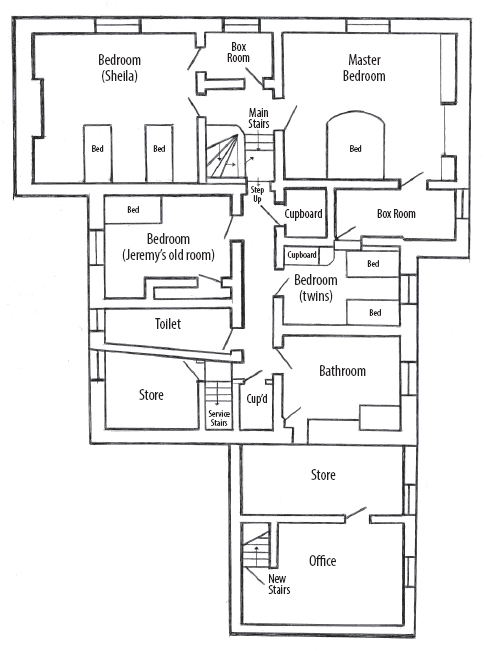

White House Farm First Floor 7 August 1985

Preface

Suicide Girl Kills Twins and Parents bellowed the Daily Express headline on 8 August 1985. Beside a hauntingly beautiful photograph of the young woman and her two smiling children the article began: A farming family affectionately dubbed the Archers was slaughtered in a bloodbath yesterday. Brandishing a gun taken from her fathers collection, deranged divorcee Sheila Bamber, 28, first shot her twin six-year-old sons. She gunned down her father as he tried to phone for help. Then she murdered her mother before turning the automatic .22 rifle on herself.

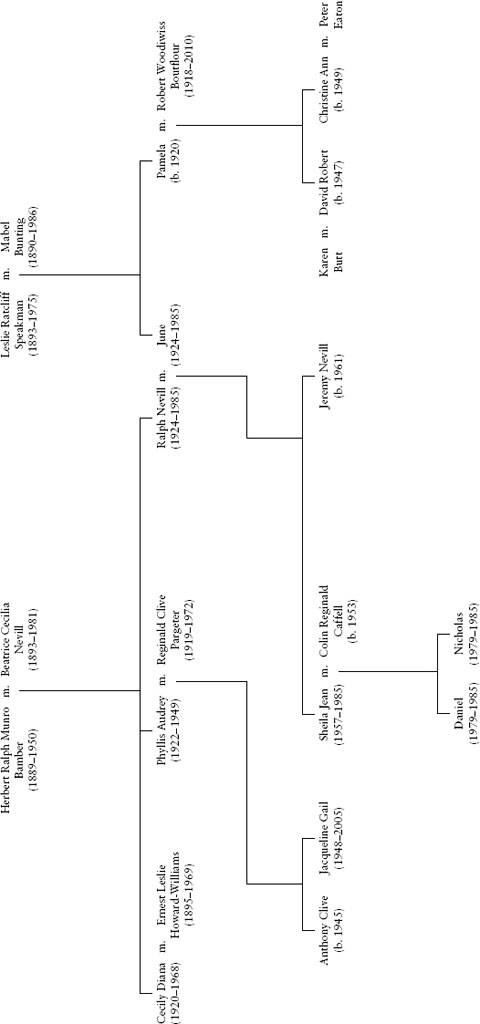

Twenty-four-year-old Jeremy Bamber had raised the alarm shortly before 3.30am on Wednesday, 7 August 1985. He told police that he had just received a phone call from his father to the effect that Sheila had gone berserk with a gun. Officers met him at the family home, White House Farm in Tolleshunt DArcy, Essex; Jeremy worked there but lived alone three miles away. Firearms units arrived but it wasnt deemed safe to enter the house until 7.45am. They found sixty-one-year-old Nevill Bamber in the kitchen, beaten and shot seven times; his wife June, also sixty-one, lay in the doorway of the master bedroom, shot eight times; Sheilas six-year-old twin sons, Nicholas and Daniel, had been repeatedly shot in their beds, while Sheila herself lay a few feet from her mother, the rifle on her body, its muzzle pointing at her chin and a Bible at her side. The two bullet wounds in her throat caused some consternation, but the knowledge that she suffered from schizophrenia, coupled with Nevills call to his son and the apparent security of the house, convinced police that it was a murder-suicide.

For weeks to come, the tabloids gorged themselves on salacious stories about Hell Raiser Bambi, the girl with mad eyes, whom they claimed had been expelled from two schools before becoming a top model with a wild social life that resulted in a 40,000 drug debt linking her to a string of country house burglaries. June Bamber, too, was condemned as a religious fanatic with little else to her character. When journalist Yvonne Roberts visited Tolleshunt DArcy that September for a more restrained article in Londons Evening Standard, one local told her: What upsets us is that the whole familys life has been reduced to a series of newspaper headlines. And none of them has got it right.

Jeremy Bambers surviving relations believed the police hadnt got it right either. They informed officers that Sheila had lived for her children and had no knowledge of firearms, while the medication she took to control her illness left her physically weak and uncoordinated. The rifles magazine was stiff to load and the killer had done so at least twice in order to disgorge twenty-five shots, all of which had found their mark. The killer had also overpowered Nevill Bamber, who was six feet, four inches tall and physically very fit.

Furthermore, the dissenting relatives told how they had located the rifles silencer (technically known as a sound moderator) in a cupboard at the farm on the Saturday after the murders. It bore red paint which forensic experts linked to scratches on the mantelpiece above the Aga where Nevill had been found, and blood inside the baffles was identified as belonging to Sheilas blood group. Since the first wound to her throat was incapacitating and the second immediately fatal, it followed that she could not have gone downstairs after shooting herself to put away the silencer; nor did she have the reach to pull the trigger when the silencer was attached to the weapon.

The Bambers were a wealthy family. Soon after the murders, Jeremy began selling antiques from the farmhouse and his sisters flat in London, ostensibly to raise funds for the death duties he would be required to pay on his inheritance. But a few weeks later his ex-girlfriend Julie Mugford came forward with an extraordinary story: fuelled by jealousy and greed, Jeremy had been plotting to kill his family for at least eighteen months and had hired an assassin to carry out the murders for 2,000. Detectives quickly established that the alleged hit man (a local plumber) had a solid alibi and concluded that Jeremy had committed the murders himself; he had already admitted to stealing almost 1,000 from the family caravan site six months earlier to prove a point. In her testimony, Julie stated that Jeremy had ended their relationship when she became too upset at having to conceal the truth about the shootings. He dismissed her claims as the bitter fulminations of a jilted woman she was enraged that he had left her for someone else. But seven weeks after the murders, he was charged with killing his family.

It comes down to this: do you believe Julie Mugford or do you believe Jeremy Bamber? declared the judge at Chelmsford Crown Court in October 1986. The jury deliberated the question overnight and by a 102 majority found Jeremy guilty. Told that he would serve a minimum of twenty-five years in prison, in 1988 his tariff was increased to whole life.

Too forgettable, was Madame Tussauds verdict one month after the trial, when asked by a Today reporter if they would be installing a wax mannequin of Jeremy Bamber in the Chamber of Horrors. But largely through his own efforts, Jeremy has remained in the public eye, steadfastly maintaining his innocence. Either he is truthful and the British justice system has meted out an appalling miscarriage of justice against a man already suffering an incalculable loss, or he is a callous, calculating killer whose attempts to gain freedom are another example of his psychopathy.

Since the failure of his first appeal in 1989, Jeremy has fastidiously worked his way through the case papers, putting forwards various scenarios absolving him of guilt. Although any of these have yet to result in an acquittal, he has seized the chance to distribute sections of the material to the media and other interested parties. As a consequence, virtually every news story about the murders originates from him via his legal team and campaigners.

One commentary on the case describes this repeated overlaying of detail through the production of new evidence as having the effect of dilating rather than clarifying the story and making the violence at its core even harder to grasp. A detailed examination of all the issues raised by Jeremy Bamber and his successive lawyers in their attempts to overturn his conviction falls outside the scope of this book; indeed, it would fill a book of its own. The list of sources includes those websites where more information can be found, but every issue put forward since the trial has been considered by various administrations, including the Police Complaints Authority, the City of London Police, the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) and the Appeal Court itself. None have been upheld. Likewise, reports commissioned from experts by Jeremys lawyers since his case last reached the Appeal Court in 2002 have failed to convince the CCRC that there is any new evidence or legal argument capable of raising a real possibility of quashing his conviction.