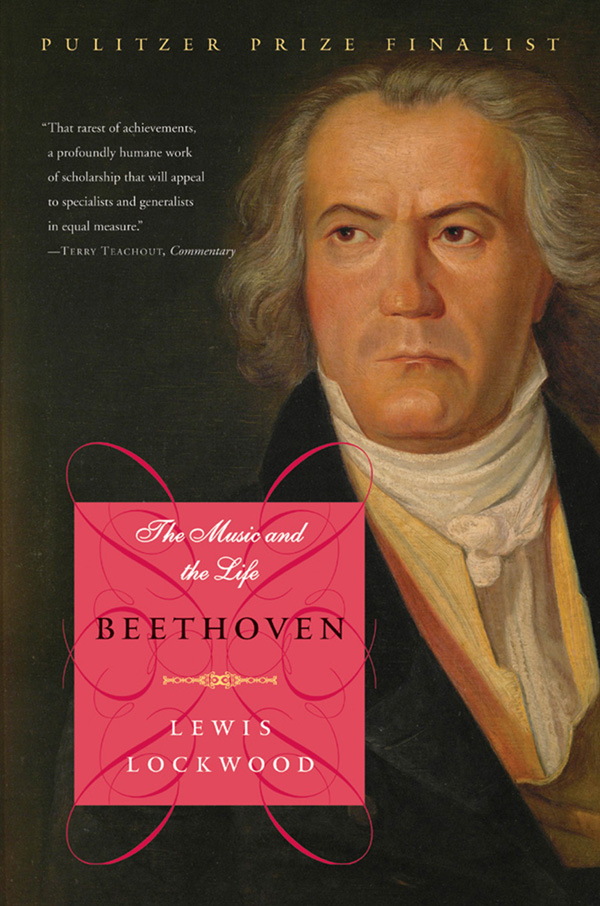

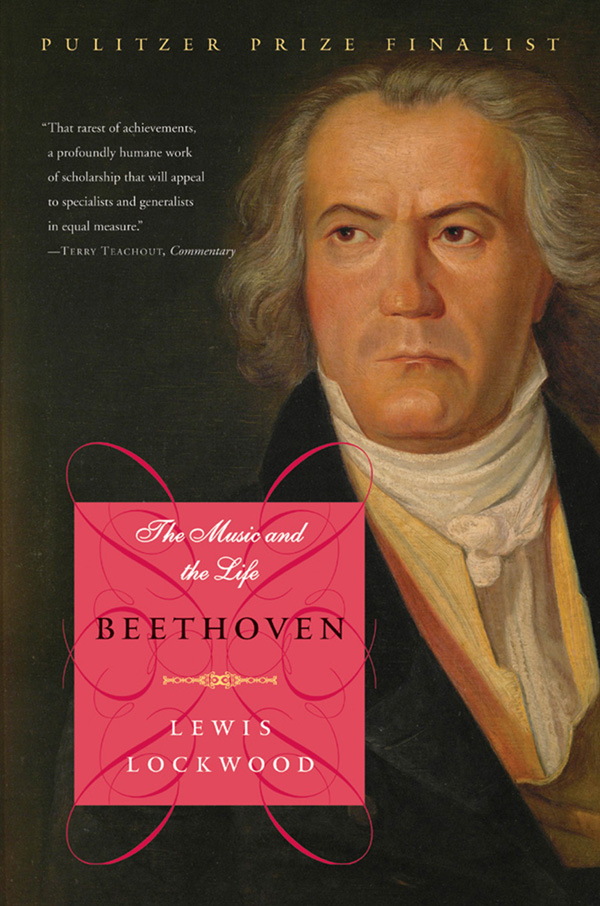

B EETHOVEN

T HE M USIC

AND THE L IFE

Lewis Lockwood

To Ava

C ONTENTS

PART ONE: THE EARLY YEARS

17701792

PART TWO: THE FIRST MATURITY

17921802

PART THREE: THE SECOND MATURITY

18021812

PART FOUR: THE FINAL MATURITY

18131827

The symbol *W denotes a music example in score, located on

W.W. Nortons Web site at www.wwnorton.com/trade/lockwood.

The first such reference appears on page 55.

Note to the paperback edition: In this edition I have corrected a number of typographical and other errors, some of which were pointed out to me by readers. Among them are Jaime Urrea, Franz Schulze, G.W. Spence, and, especially, Robert Levin, to all of whom I am grateful.

T his book attempts to portray Beethoven as man and artist, with a primary focus on his music but with ample attention to his life, career, and milieu. My aim is to present his life mainly through his development as a composer, rather than to devote each chapter to a biographical narrative combined with a partial overview of his artistic growth. The complex question of how to interweave the two dimensionsthe musical and the biographicaland to what extent they can be interwoven is itself an issue that is discussed in the book and that hovers over it throughout.

Although separate chapters are devoted to biography and to critical discussion of the music, my hope is that readers who care more about Beethovens life will also read those that deal with works and genres; and that readers interested mainly in the music will cross the bridge to the biography. As for readers most interested in the historical, political, and cultural framework in which Beethoven came of agethe turbulent Europe of the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, the years of war before and during the reign of Napoleon, and the vast turning of the wheel that brought on the Industrial Revolution and the age of Romanticismthis book is meant to give such readers access to Beethovens works both as reflections of outer influences and as imaginative products of a richly endowed musical mind.

I have found models for this approach in two biographies: Abraham Paiss Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein (1982), and Nicholas Boyles Goethe: The Poet and the Age (19922000). In Paiss biography chapters with titles in italics provide an almost entirely nonscientific biography of Einstein, while the nonitalicized chapters (most of them) are the equivalent of a scientific biography. In Boyles book on Goethe, biographical matters and criticism of the poetry and drama alternate with one another, sometimes as separate sections within chapters. I have not used italics or any other way of differentiating chapter titles, but have written on Beethovens works with the lay reader in mind at what I hope will be a highly accessible descriptive level.

Although some chapters reflect my interest in the study of Beethovens creative process, much of the musical discussion in the book consists of short critical accounts of a large number of works, including his most important ones in every genre. These commentaries are inevitably brief, as they must be in a book of moderate length, but I have tried to bring out salient and important aspects of the works and to frame my comments within the context of Beethovens changing styles and changing ways of shaping larger musical compositions over the course of his lifetime. The earlier chapters reflect on the special problem that Beethoven faced as a young and gifted artist who found that his contemporaries hoped that he would become a second Mozart, a role that was not only prescribed for him by his teachers and knowledgeable patrons but that he willingly took on in his early years. The difficulty for the young Beethoven of being a truly rebellious original and of accepting his destiny as the main successor to Mozartas lofty a model as has ever existed in musicis a crucial aspect of his early development, and it plays out through his entire career in different ways. The later chapters, in a partial parallel, show us Beethoven in his last years, with great achievements behind him, now surmounting the crisis of finding still another new artistic path on which to continue, reaching back through several generations and finding new models in the music of Handel and, especially, Bach.

Within every specialist lurks a generalist yearning to get outa sensation I have never felt more keenly than while writing this book. Accordingly, this broad survey can be read as a prcis of many specialized monographs, many already written and some still unwritten. Throughout the book, in text and footnotes, I have tried to take account of the current specialized scholarly literature on Beethoven. To make the discussion of Beethovens works as accessible as possible, music examples within the book have been kept to the barest minimum, but a large number of examples in score will be found on a special Web site for this book maintained by the publisher at www.wwnorton.com/trade/lockwood. Each reference to an example on the Web site is marked by *W and a number in the text.

Growing up in New York City in the 1940s, I first heard Beethovens orchestral works, and much other music, played by the New York Philharmonic at Young Peoples Concerts at Carnegie Hall. As a young cellist I played his cello sonatas, trios, string quartets, and symphonies, first in the incomparably stimulating atmosphere of the High School of Music and Art, and later at Queens College of the City of New York. The Queens College faculty then included, among others, Edward Lowinsky, Karol Rathaus, Leo Kraft, Sol Berkowitz, John Castellini, and other eminent teachers in history, philosophy, and literature. Many years later, after having taught Beethoven at undergraduate and graduate levels at Princeton University and at Harvard University, I still play Beethovens chamber music, and thinking and writing about him has become a main professional activity. I found out in my teenage years that there was a substantial critical literature on Beethoven, starting with the essays of Donald Francis Tovey, which I discovered on the shelves of the Bainbridge Avenue Public Library in the Bronx. And I can remember wondering, while playing the A major Cello Sonata, Opus 69, why certain parallel passages in the exposition and recapitulation of the first movement didnt exactly agree in their intervals, although every other parallel pair was identical. Many years later, when I was studying Beethovens compositional methods through his sketches and autographs, the answer came into my hands unexpectedly when I was given the opportunity to study Beethovens autograph manuscript of the first movement of this very cello sonata. The manuscript was then owned by the late Felix Salzer, an eminent theorist and former student of Heinrich Schenker, who invited me to study it at his home in New York and to decipher its many complex revisions and alterations. This experience taught me firsthand what it means to follow the complexities of Beethovens notation as direct evidence of his restless, exploratory musical thinking.

At graduate school in Princeton in the 1950s, among seminars in music history that I took with Oliver Strunk, Arthur Mendel, and Nino Pirrotta, a graduate course on Beethoven biography was offered by Elliot Forbes, then a member of the Princeton faculty. At that time Forbes was well along in his work on a new edition, published in 1964, of the great nineteenth-century Life of Beethoven by Alexander Wheelock Thayer that I was fortunate enough to read in manuscript before it appeared in print. My indebtedness to Elliot Forbes, later my colleague at Harvard, is many-sided. In 1977 I renewed my early friendship with Maynard Solomon, whose brilliant Beethoven biography, published that same year, broke new ground in its blending of close scholarly discussion of Beethovens life with new insights drawn from Solomons psychoanalytic background.

Next page