F OR FORTY HOURS the snow tumbled over New England, settling up to six feet deep on every city, forest, and frozen river. At the blizzards height, on Tuesday, February 7, 1978, President Carter declared coastal Massachusetts a federal disaster area. After a second record night of snow, the governor ordered all citizens not engaged in relief work to stay home. Interstate 93 ran white as a glacier, its ramps curving into the moraine of downtown Boston.

Just when the world seemed about to suffocate, the last flakes fell. But then the snow turned to ice, and the weight of precipitation became unbearable. Power grids snapped, hospitals switched to emergency supplies, stores and restaurants stayed dark. Biographical researchers trapped in digs near Harvard University found themselves with nothing to eat and nowhere to buy food. Another night of almost total silence came on. It was difficult not to think of entombment.

Thursday morning brought sunshine and a sense of life returning. Icicles sliced the light. The first shovelers got to work in front of dorm doorways. Students on skis poled across Harvard Yard. Pedestrians struggled to follow, plunging waist-deep at every step. There was still little noise: only the dry squeak of snow underfoot, and an occasional shout. Then some invisible person threw open a second-floor window, mounted a pair of speakers on the sill, and blasted the finale of Beethovens Fifth Symphony into the crisp air.

Nothing was ever so loud, so bright as that C-major fanfare, surging over a blare of trombones with all the force of Old Faithful. It was Carlos Kleibers DGG recording with the Vienna Philharmonicnew then, legendary now. Skiers, shovelers, and plungers stood transfixed. After three great leaps (the last requiring an extra beat to discharge all its sound), the chords subsided, only to gather strength for higher and higher ascents, to the crest of the scale and beyond, until, geyser-like, they broke into exultant syncopations.

So far, nobody had heard a melody, or any harmonies that could not be blown through a mouth organ. And when a tune finally came, played at maximum volume by three horns, it was close to banal. So why, after the music ended ten minutes later, with forty-eight thunderclaps of C major, were some of the listeners crying?

Of all the great composers, Beethoven is the most enduring in his appeal to dilettantes and intellectuals alike. Bach and Mozart have had their periods of misapprehensionthe former mocked as pass even in his own lifetime, the latter miniaturized by the Victorians. Handel, in contrast, was giantified, but as the composer of Messiah mainly, at cost to his operatic achievement. HaydnBeethovens teacheris admired more by connoisseurs than by the general public. Schubert was still being caricatured as an idiot-savant songster long after World War II. Brahms has never gone down well in France; Bruckner is a minority taste outside the German-speaking world; and Sibelius, who once seemed sure of a seat on Parnassus, has been replaced by the masturbatory Mahler. Chaque ge son got.

Beethoven was recognized in his teens as a genius of the first order. He was less of a prodigy than Mozart or Mendelssohn, but surpassed them in the bigness of his aspirations. From the moment he arrived in Vienna at the age of twenty-one, that citycapital of the musical worldcelebrated him. Princes vied for the honor of putting him up in their palaces. (Mozart, just a few years earlier, had to dine below the valets but above the cooks.) After Haydn died in 1809, Beethoven, not yet forty, became the worlds most famous composer. He remains that almost two centuries later. Climb the mildewed stairway of the most obscure building he ever lived in, and you can be fairly sure of bumping into a Welsh choral society, or a party of reverent Japanese.

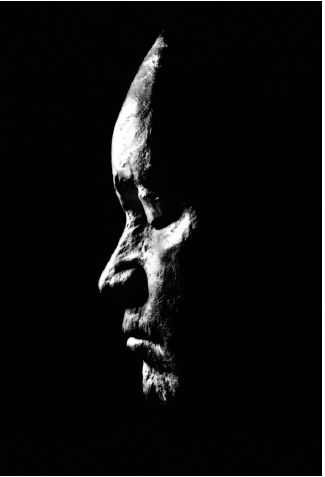

What draws them is Beethovens universality, his ability to embrace the whole range of human emotion, from dread of death to love of lifeand to the metaphysics beyondreconciling all doubts and conflicts in a catharsis of sound. That anonymous broadcaster of the finale of the Fifth Symphony across Harvard Yard after the blizzard of 78 knew just where to drop his needle: the point at which the transition from the C-minor scherzo resolves fortissimo into C major. He also understood (even if his listeners did not) the symbolism of that transition, the most claustrophobic passage in all music. It begins with a sudden hush, as if a great weight has blocked out light and air. For a moment, all is frozen shock, the strings holding an indeterminate chord, and then an almost inaudible beating of drums is heard. Stifled moans sound in the violins: terrified, fragmentary phrases that try to rise without success. The drumbeats, hesitant at first, become a constant throb, as if hysteria is building, while the moans try again to rise. With agonizing difficulty, they begin to succeed, and the weight overhead seems to lighten. Airy woodwinds amplify a gathering crescendo, joined by trumpets and hornsthen all restraint is loosened, and the whole orchestra breaks free, and every hair stands up on your neck.

There are countless moments such as this in Beethoven, but not one like this: his originality prevents him repeating himself. (At the same time, there is a signature quality, unmistakable as the hand of Picasso.) Radical to begin with, Beethoven grew more radical with age; some of his late works reinvent themselves movement by movement. The string Quartet in B-flat, Op. 130, traverses more styles in fifty minutes than Wagner did in fifty years. And after finishing it with a stupendous fugue, Beethoven still had enough inspiration left over to write an alternative finalehis last published compositionthat has the effect of transforming the whole work in retrospect. The other movements still float in order astern, but they look closer and more companionable, seen from a less lofty masthead.