All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

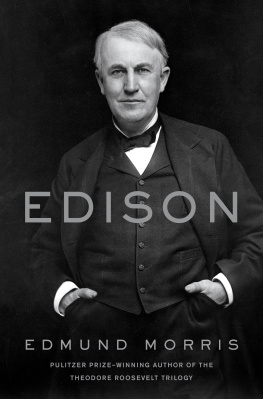

I do not find it so easy to talk about my Father.I have yet to find a biography of him that satisfies me as a picture of the whole man. The emphasis is so much on what he did that few people know what he was.

I have been astonished at times to find the general impression is that he was a sort of superhuman lightning rod, pulling down inventions from heaven at willa miraculous robot who never got tireda disembodied brain whose success, bringing fabulous riches, was effortless and assured, in spite of a background of abject poverty, almost total lack of education, and no personal life at all. I may say that the picture is not quite accurate.

PROLOGUE

1931

T OWARD THE END, as at the beginning, he lived only on milk.

When he turned eighty-four in February, and pretended to be able to hear the congratulations of the townspeople of Fort Myers, and let twenty schoolgirls in white dresses escort him under the palms to the dedication of a new bridge in his name, and shook his head at being called a genius by the governor of Florida, and gave a feeble whoop as he untied the green-and-orange ribbon, and retreated with waves and smiles to the riverside estate he and Mina co-owned with the Henry Fords, he declined a slice of double-iced birthday cake and instead drank the fourth of the seven pints of milk, warmed to nursing temperature, that daily soothed his abdominal pain.

From earliest youth he had half-starved himself, faithful to the dictum of the temperance philosopher Luigi Cornaro (14671566) that a man should rise from the table hungry. It was not always a matter of choice. At times during his teenage years as a gypsy telegrapher, he had wandered the streets of strange cities, unable to afford a cheekful of tobacco. But even in early middle age, while earning big money and enabling two successive wives to fatten on haute cuisine, he would eat no more than six ounces a mealgenerally only fourand drink nothing except milk and flavored water. A man cant think clearly when hes tanking up. His one indulgence was cheap Corona cigars, which he smoked, or rather chewed, by the boxful and liked not for their price but for their strong, coarse taste.

My message to you, he advised his fellow citizens in a valedictory radio broadcast from his botanical library, is to be courageous. I have lived a long time. I have seen history repeat itself time and again. I have seen many depressions in business. Always America has come back stronger and more prosperous.

Before returning home at winters end to New Jersey, he prayed to some power other than God (whose existence he denied) to be spared long enough to finish his current round of botanical experiments. Give me five more years, and the United States will have a rubber crop that can be utilized in twelve months time.

It was clear, however, when he arrived at the station in Newark, that he would not see another spring. He was frail and stooped under his thick fall of white hair, and needed help to walk. Three of his six children were on hand to greet him. Outside, a warm thunderstorm was pounding down. Mina threw a protective rug over her husbands shoulders as he tottered toward a waiting automobile for the short drive to West Orange.

Next morning, employees at his vast laboratory complex up Main Street waited for the Old Manas he had been known since his twentiesto punch in early as usual. But for the rest of June and all of July, he uncharacteristically remained at Glenmont, his mansion in the gated confines of Llewellyn Park. On the first day of August he appeared at the front door, dressed for a country excursion, only to collapse and be carried upstairs to bed. Three physicians arrived in a hurry, one of them by chartered plane. That night they announced that their patient was in failing health, afflicted by chronic nephritis on top of his metabolic disorder. Aware that Wall Street would react negatively to this news, they added, The diabetic condition now is under control, and the kidney condition seems improved.

N EWSROOMS AROUND THE world hastened to update the obituary of Thomas Alva Edison. They had been doing so for fifty-three years, ever since his self-proclaimed greatest invention, the phonograph, won him overnight fame. Then and now, journalists marveled that such an acoustic revolution, adding a whole new dimension to human memory, could have been accomplished by a man half deaf in one ear and wholly deaf in the other.

Even the most text-heavy periodicals lacked enough column inches to summarize the one thousand and ninety-three machines, systems, processes, and phenomena patented by Edison.he had invented two hundred and fifty sonic devices: diaphragms of varnished silk, mica, copper foil, or thin French glass, flexing in semifluid gaskets; dolls that talked and sang; a carbon telephone transmitter; paraphenylene cylinders of extraordinary fidelity; duplicators that molded and smoothed and swaged; a pointer-polisher for diamond splints; a centrifugal speed governor for disk players; a miniature loudspeaker utilizing a quartz cylinder and ultraviolet light; a dictating machine; audio mail; a violin amplifier; an acoustic clock; a radio-telephone receiver; a device that enabled him to listen to the eruptions of sunspots; a recording horn so long it had to be buttressed between two buildings; bone earbuds that could be shared by two or more listeners, and a voice-activated flywheel.

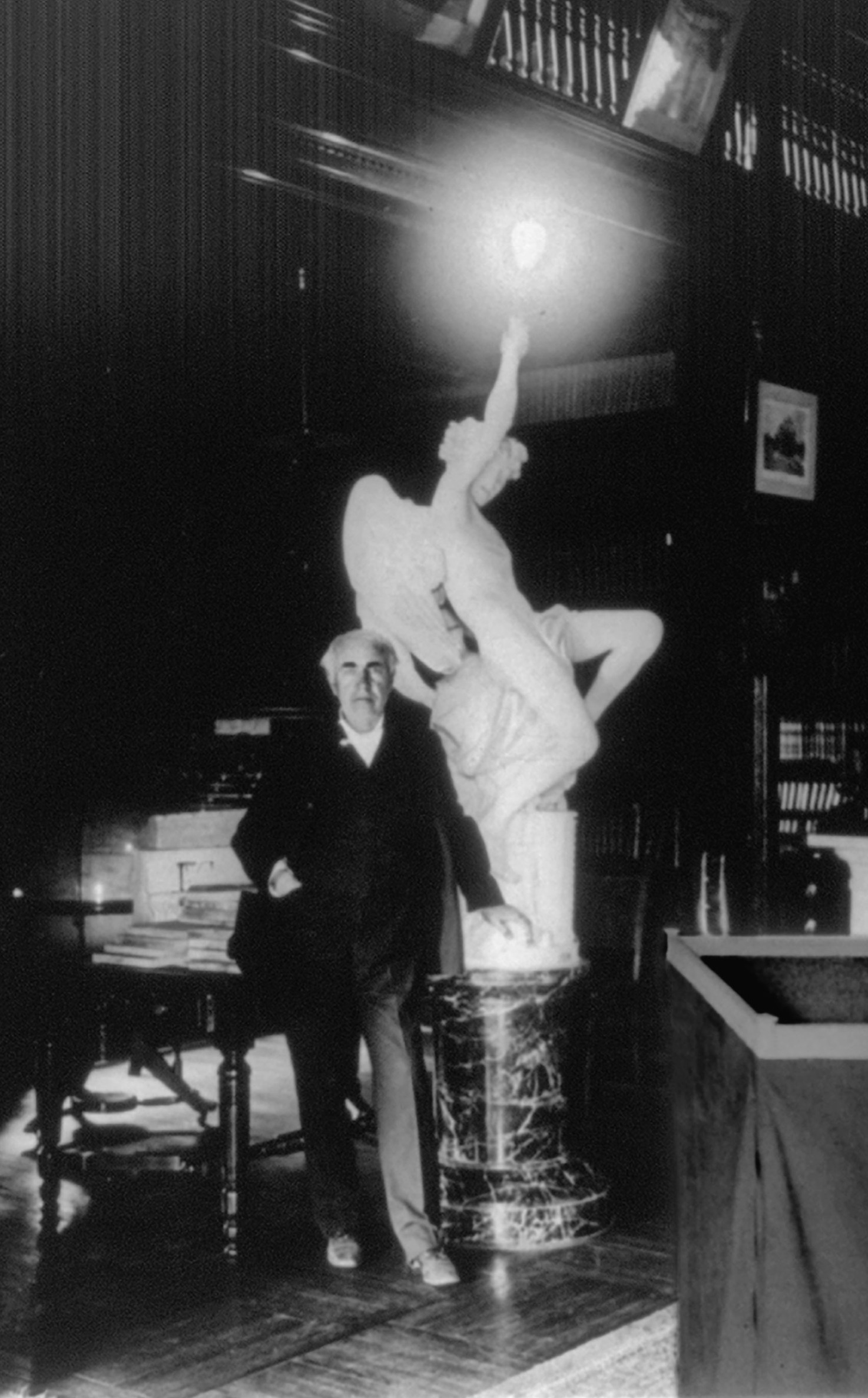

He was even more legendary for his creation of the long-burning incandescent lightbulb, accompanied by two hundred and sixty-three other patents in illumination technology. That number could be increased by one, had he not made his X-ray fluoroscope available without license to all medical practitioners. Most spectacularly, Edison had designed, manufactured, powered, and built the worlds first incandescent electric lighting system. At the flick of a switch, one September evening in 1882, he had transformed the First District of lower Manhattan from a dimly gaslit warren into a great spread of glowing jewels.

Out of his teeming brain and ever-mobile hands (the rest of him rigid with concentration, as he hunched over his tools and flasks) came the universal stock ticker, the electric meter, the jumbo dynamo, the alkaline reversible battery, the miners safety lamp, slick candy wrappers, a cream for facial neuralgia, a submarine blinding device, a night telescope, an electrographic vote recorder, a rotor-lift flying machine, a sensor capable of registering the heat of starlight, fruit preservers, machines that drew wire and plated glass and addressed mail, a metallic flake maker, a method of extracting gold from sulfide ore, an electric cigar lighter, a cable hoist for inclined-plane cars, a self-starter for combustion engines, microthin foil rollers, a sap extractor, a calcining furnace, a fabric waterguard, an electric pen, a sound-operated horse clipper, a moving-sphere typewriter, gummed tape, the Kinetograph movie camera, the Kinetoscope projector, and moving pictures with sound and color. He built the worlds first film studio, the worlds biggest rock crusher, tornado-proof concrete houses, scores of power plants, and an electromagnetic railway complete with locomotive, trolleys, brakes, and turntable. He dreamed up a Goldbergian set of variations on the theme of telegraphy, including duplex, quadruplex, and octoplex devices that transmitted multiple messages simultaneously along a single wire, grasshopper signals that leaped from speeding trains, and receivers that chattered out facsimiles or turned dots and dashes into roman type. If he had not been so busy inventing other things in the early 1880s, he could have combined his discoveries of etheric sparking, thermionic emission, extended induction, and rectifying reception into the wireless technology of radio.