FOUNDING EDITOR

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.

BOARD MEMBERS

Alan Brinkley, John Demos, Glenda Gilmore, Jill Lepore

David Levering Lewis, Patricia Nelson Limerick, James McPherson

Louis Menand, James H. Merrell, Garry Wills, Gordon Wood

James T. Campbell

Middle Passages: African American Journeys to Africa, 17872005

Franois Furstenberg

In the Name of the Father: Washingtons Legacy, Slavery, and the Making of a Nation

Karl Jacoby

Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History

Julie Greene

The Canal Builders: Making Americas Empire at the Panama Canal

G. Calvin Mackenzie and Robert Weisbrot

The Liberal Hour: Washington and the Politics of Change in the 1960s

Michael Willrich

Pox: An American History

James R. Barrett

The Irish Way: Becoming American in the Multiethnic City

Stephen Kantrowitz

More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 18291889

Frederick E. Hoxie

This Indian Country: American Indian Activists and the Place They Made

Ernest Freeberg

The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America

A LSO BY E RNEST F REEBERG

The Education of Laura Bridgman

Democracys Prisoner

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA Canada UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright Ernest Freeberg, 2013.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Illustration credits appear .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Freeberg, Ernest.

The age of Edison : electric light and the invention of modern America / Ernest Freeberg.

pages cm. (Penguin history of American life)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101-60547-9

1. Technological innovationsUnited StatesHistory. 2. Technological innovationsSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. 3. Electric lightingUnited StatesHistory. 4. Edison, Thomas A. (Thomas Alva), 18471931. 5. Edison, Thomas A. (Thomas Alva), 18471931Contemporaries. I. Title.

T173.4.F74 2013

303.48'3097309034dc23

2012039513

To my parents

Contents

Introduction

Inventing Edison

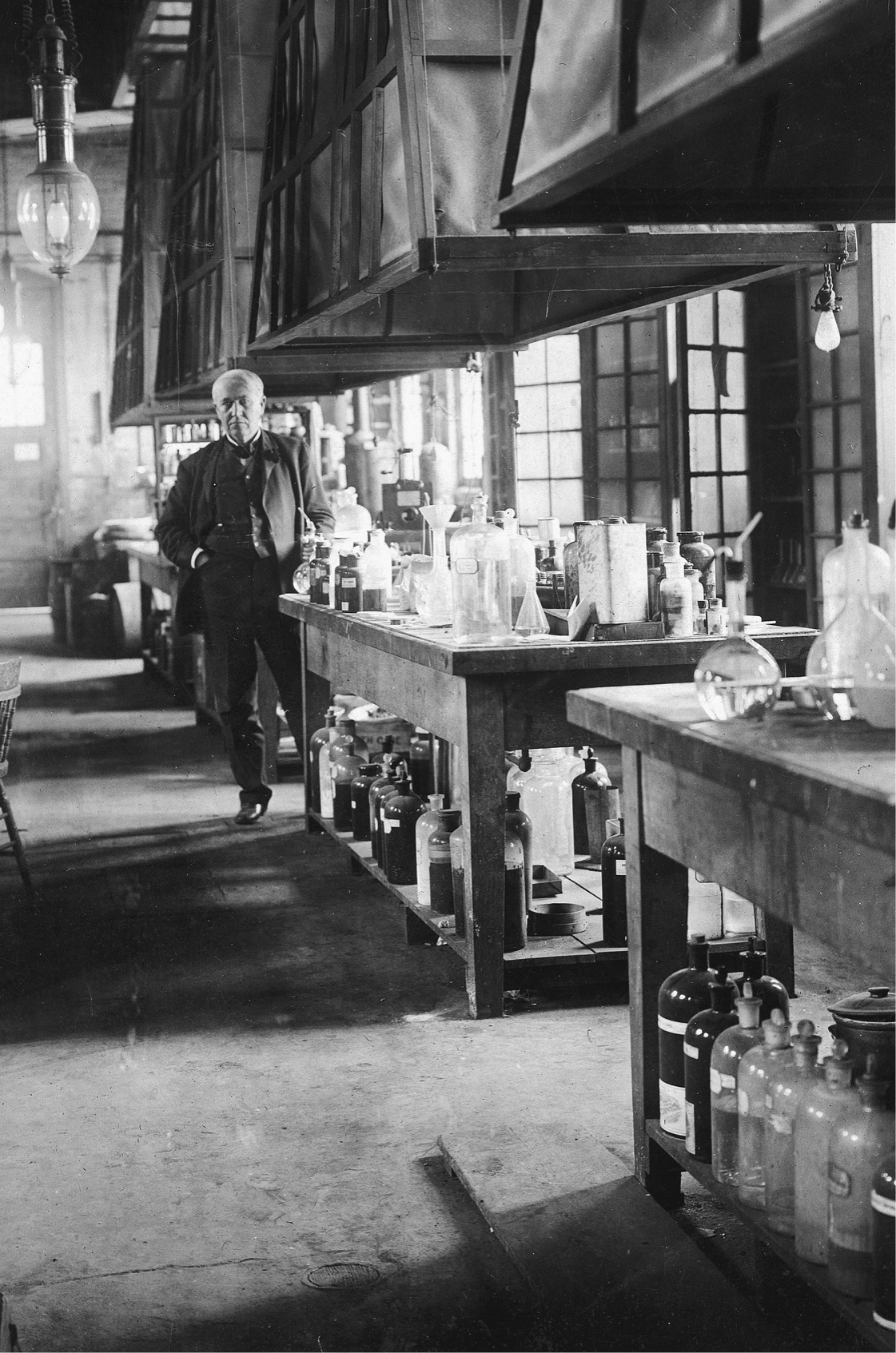

O il lamps burned late into the night at Edisons laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, all through the fall of 1879. Months earlier the famed inventor had sent stock markets reeling with his announcement that he had solved one of the great technological puzzles of the age, the secret to transforming electricity into light. Edison promised the world that he would soon unveil a lamp that would make candles, kerosene, and coal gas obsolete. With remarkable intuition and tremendous persistence, the thirty-two-year-old inventor had surmounted one technological challenge after another in his relentless pursuit of a viable incandescent electric light. Through it all he was praised by newspaper reporters as a wizard, pressured by his financial backers for moving too slowly, and scorned by scientific experts on both sides of the Atlantic for promising what he could not possibly deliver.

Edison felt sure that he stood on the brink of success, but he still lacked an essential ingredient: a working filament. He needed to find a substance that could handle the tremendous heat of an electrical current and, when placed in the protective atmosphere of a vacuum bulb, would incandesce, glowing instead of burning up. Mulling over the problem late one October evening, the inventor absentmindedly rolled in his fingers a thread of lampblack, a form of carbon soot he had been gathering for an entirely different project. Acting on a hunch that the black sliver in his hand might provide the solution, he arranged for a test that very evening. Sealed in a vacuum, then fed current from a battery, the filament glowed long enough to convince him that he was on the right track. Over the next couple of weeks Edison and his team tested a range of other carbon filamentsshavings of cardboard and paper, cotton soaked in tar, and even fishing line. Some failed immediately, others glowed for a time, but none worked as well as a simple filament of carbonized cotton thread. First lit after midnight on October 22, the bulb glowed through the night. Edison and his team stayed up to watch, and when the bulb finally burned out nearly fourteen hours later, they felt certain that the fundamental problem had been solved. While much remained to be done, Edison had the proof he needed that his system would work. Filing for a patent the next month, he made ready for his first public demonstration of his new light, while newspapers spread the news that the great inventor had found SUCCESS IN A COTTON THREAD .

F or more than a century Americans have regarded the creation of the incandescent light as the greatest act of invention in the nations history, and the light bulb has become our very symbol of a great idea. We associate the bulb with a eureka moment, the modern version of an ancient metaphor linking light with insight. A recent study found that just the presence of a lit incandescent bulb helped a group of research subjects to think more creatively, solving problems faster than others who worked under an equally bright but less inspiring fluorescent light. As the study concludes, exposure to an illuminating lightbulb primes bright ideas.

Just as automatically, we think of Thomas Edison as the man to thank for our electric light, the one whose own burst of inspiration gave us the invention that has remained one of the signal achievements of our technological age. For good reason we remember him as one of the greatest inventors of all time, and with due respect to the phonograph and the moving picture, most consider the incandescent light his greatest legacy. For decades after Edisons breakthrough at Menlo Park, journalists often called all electric lamps Edisons light, and long after he retired from active research in the field, the public honored him as the Man Who Lighted the World. As one popular textbook sums it up, A whole way of life had been revolutionized by one mans skill, insight and enterprise.

Though they acknowledge Edisons great accomplishment, historians of technology have long shown the limitations of this view, which is in fact more hero worship than history. They remind us that Edisons success with a carbon filament on that October evening in 1879 was an important step, but only one of many needed to turn the incandescent light from an idea into a viable technology. Edisons achievement is clarified, not diminished, when we remember that he drew on the successes and instructive failures of many other inventors, working over decades and on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as a talented team of assistants in his Menlo Park laboratory. A closer look at how Edison, his partners, and his rivals developed the first working electric lights shows that the inventor does not pull insights from a void, like a bulb suddenly illuminating a dark room, but that invention is a complex social process.