CONTENTS

FOREWORD

T HERES NO QUESTION in my mind that one of Americas greatest gifts to the world is our capacity for innovation. From light bulbs and telephones to vaccines and microprocessors, our inventions and ideas have improved the livesand even saved the livesof countless people around the globe.

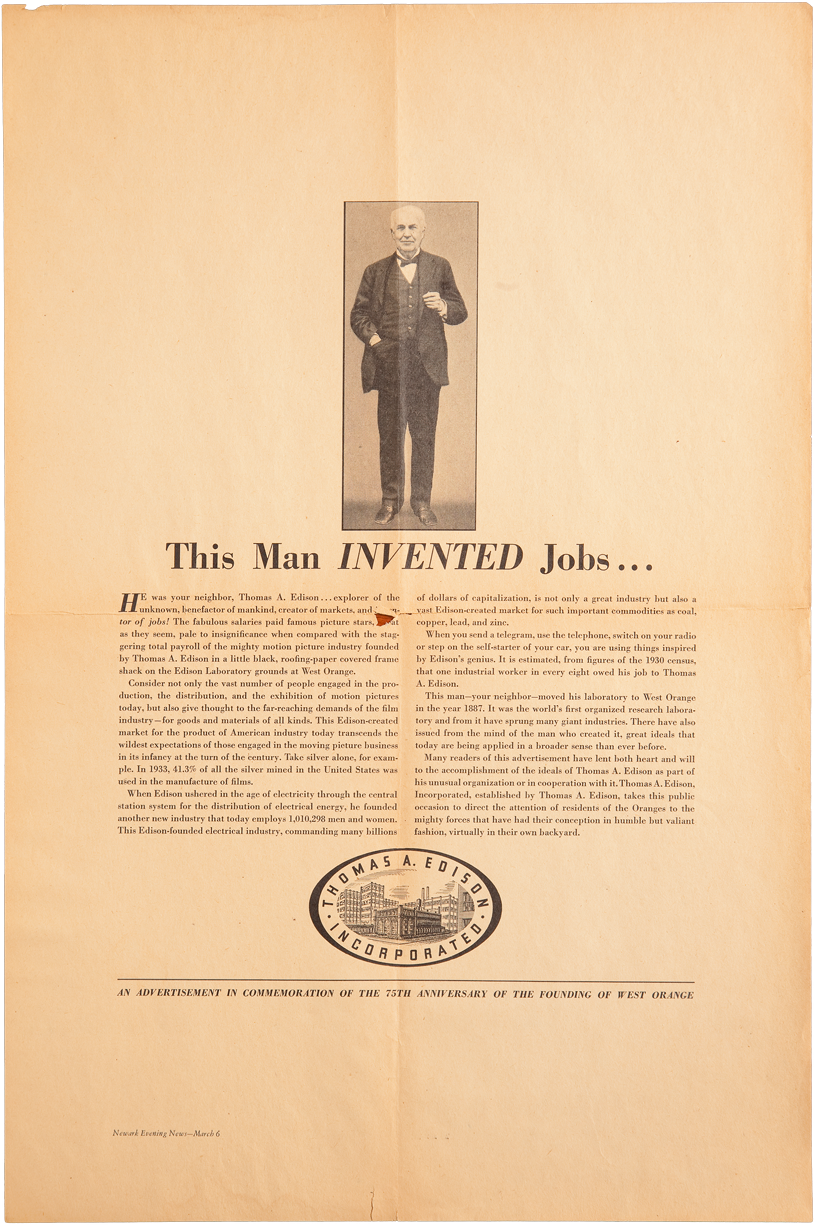

In the pantheon of American innovation, Thomas Edison holds a unique place. He became a symbol of American ingenuity and the conviction that inspiration and perspiration could lead to remarkable things.

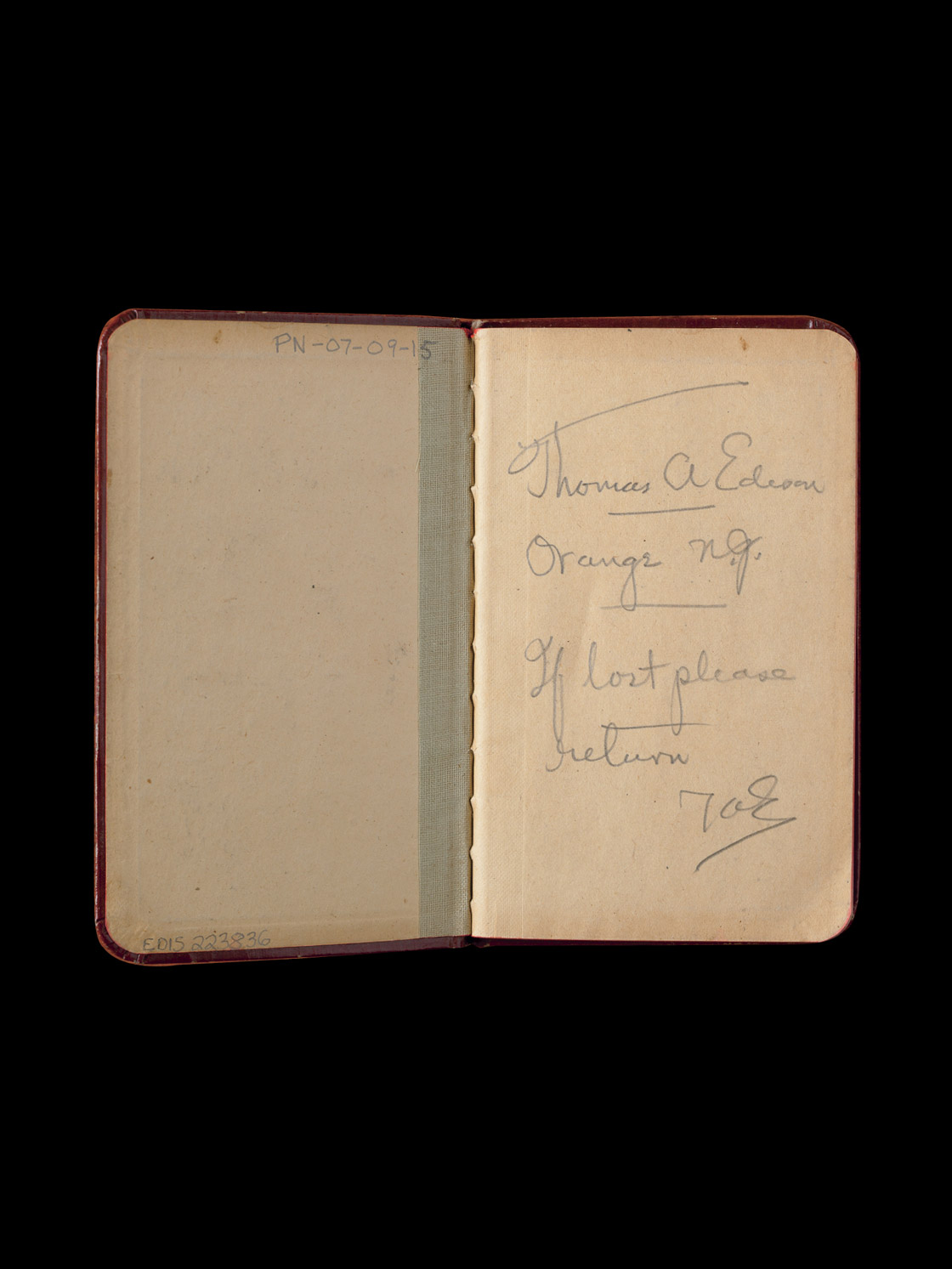

He certainly has been an inspiration to me in my career. Im lucky enough to own a few pieces of Edison memorabilia, including his sketch of an idea for improving the incandescent light bulb and some papers on finding a substitute for rubber. Looking at this work, its easy to see a creative mind continually trying to refine and improve his ideas.

Obviously, Edisons inventions were revolutionary. But as this book makes clear, the way he worked was also crucial for his success. For example, Edison consciously built on ideas from predecessors as well as contemporaries. And just as important, he assembled a team of peopleengineers, chemists, mathematicians, and machiniststhat he trusted and empowered to carry out his ideas. Names like Batchelor and Kruesi may not be famous today, but without their contributions, Edison might not be either.

Second, Edison was a very practical person. He learned early on that it wasnt enough to simply come up with great ideas in a vacuum; he had to invent things that people wanted. That meant understanding the market, designing products that met his customers needs, convincing his investors to support his ideas, and then promoting them. Edison didnt invent the light bulb; he invented the light bulb that worked, and the one that sold.

Finally, Edison recognized that inventions rarely come in a single flash of inspiration. You set a goal, measure progress using data, see whats workingand what isnt workingadjust your plan, and try again. This process can be very frustrating because it means running into a lot of dead ends. But each dead end tells you something useful. As Edison famously said, I have not failed 10,000 times. Ive successfully found 10,000 ways that will not work.

These lessons are just as true today as they were in Edisons time. Innovators still have to work in teams. (Although thats far easier to do today than at the turn of the twentieth century. Imagine what the Wizard of New Jerseys Menlo Park could have done with the tools coming out of Californias Menlo Park.) Innovators still have to understand and solve real-world problems, and they still have to persevere for the long haul. Scientists run trial after trial to perfect a new vaccine. Co-workers at software companies debug each others code.

While weve seen amazing advances in science and technology since Edisons day, these things have not changed. Thomas Edison remains a powerful exemplar of creativity, perseverance, and optimism. Even more than light bulbs and movie cameras, that may be his greatest legacy.

Bill Gates

Co-Chair, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Seattle, WA

PREFACE

A S A MEASURE OF HOW Thomas Edison changed the world, consider this: When he was born in 1847, there were no industrial research laboratories, no phonographs, no motion picture cameras, and no electric power systems, let alone practical electric lights. In 1931, the year Edison died, the United States produced 320 million lightbulbs and consumed 110.4 million kilowatt-hours of electricity. Seventy-five million Americans attended the movies each week, spending $719 million ($10.6 billion today) at the box office.

In the year of Edisons death, the New York Times estimated the value of the industries based on his inventions at more than $15 billion. His inventions made the modern age possible. Without improved telegraph, telephone, and electric power systems and the ability to record, store, and transmit sound and images, there would be no Internet or computers.

From the 1870s through the 1920s, Edisons laboratories combined knowledge, resources, and talented collaborators to turn ideas into commercial products. His laboratory workers invented the phonograph, a practical incandescent electric lighting system, and the motion picture camera. They also developed the nickel-iron storage battery, machinery for processing iron ore and manufacturing Portland cement, and a system for constructing molded cement houses. In his last experimental project, Edison created a process for extracting rubber from goldenrod, a flowering plant considered by most to be a weed.

Over the course of his long career, Edison organized and managed dozens of manufacturing and marketing companies. In the process of adopting new production and sales strategies, he helped create a mass consumer market in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Edison was also one of the first business leaders to brand himself, paving the way for Walt Disney, Steve Jobs, and other modern entrepreneurs.

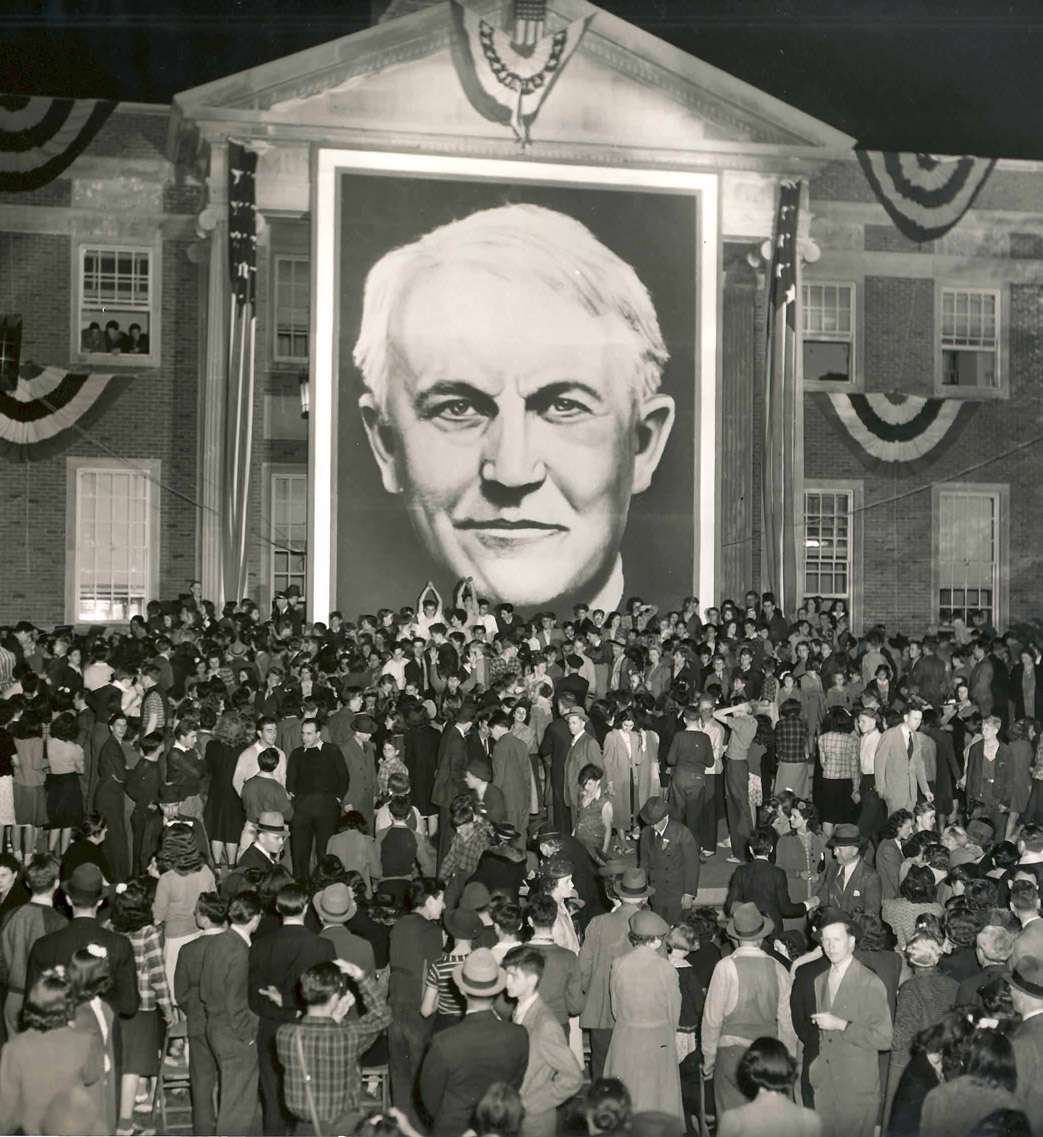

Edisons Menlo Park and West Orange labs created new industries, including electric lighting and power, sound recording, and motion pictures. Thomas A. Edison, Inc., promoted this economic legacy in the 1940s and 1950s.

Foreshadowing closer government-business relations in the twentieth century, Edison was a vocal proponent of military and industrial preparedness during the First World War. He also conducted research for the U.S. Navy during the war and served as president of the Naval Consulting Board, a group of civilian technical experts established to advise the navy on ideas for inventions.

Edison helped change the way technologies were developed. Benefiting from advances in science and the multidisciplinary labors of chemists, engineers, mathematicians, and other trained professionals, Edisons laboratories introduced new products on a regular basis. Invention shifted from talented individuals working alone to organized groups working in laboratories established specifically for industrial research and development.

A century before the modern globalization of the worlds economy, Edison operated on an international scale. He manufactured and marketed his inventions in Europe, North and South America, and Asia. He relied on globally sourced raw materials and skilled workers. Ideas and concepts generated by an international community of scientists and researchers influenced his work, and, in turn, a global public eagerly awaited his latest invention.

Edisons experience as an innovator is as relevant today as it was one hundred years ago. Edison devoted considerable attention to the questions all innovators face in modern times: Which products should I develop? How should those products be designed, manufactured, and marketed? How do I raise money to support research and development? How do I respond to competition and changing markets? Knowing Edisons response to these questions brings us closer to understanding the nature of technological innovation and creativity.