Copyright 2017 by James Hamilton-Paterson

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

Originally published in 2016 by Head of Zeus in the United Kingdom.

First U.S. Edition: December 2017

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956393

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-9736-2 (hardcover); 978-1-5416-9754-6 (ebook)

E3-20171110-JV-PC

CONTENTS

Navigation

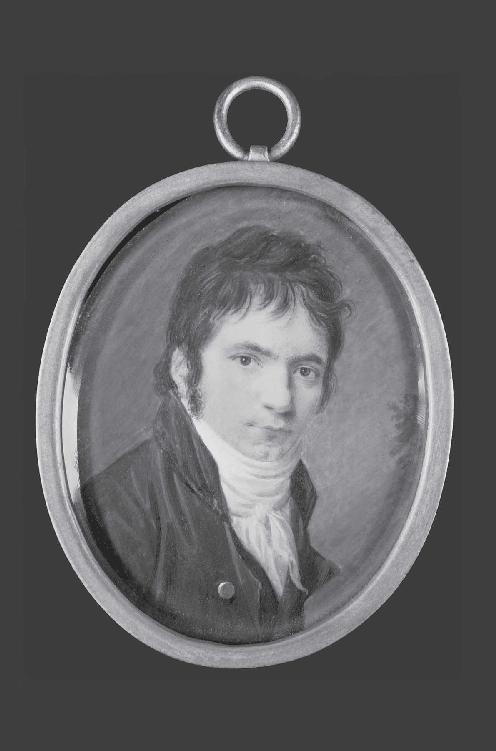

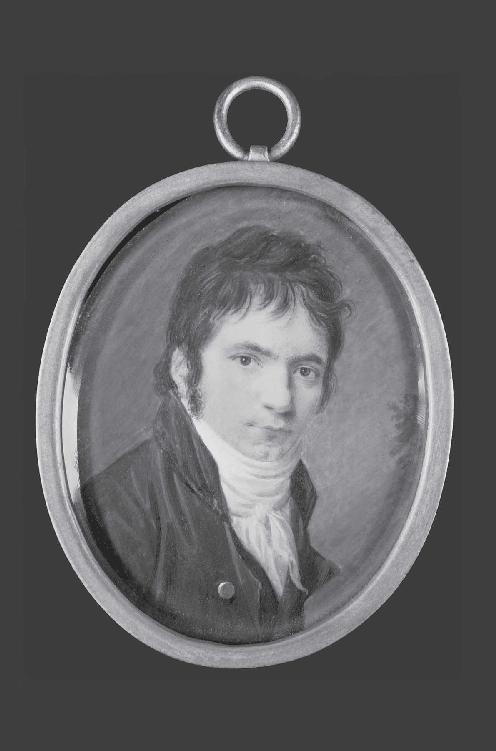

A miniature of Beethoven in 1803 done by the Danish artist Christian Horneman. It is probably the most accurate of all the earlier portraits and Beethoven himself valued it highly enough to give it to his old friend from his Bonn days, Stephan von Breuning.

C REDIT: B EETHOVEN H AUS, B ONN / B RIDGEMAN I MAGES

F or all the fame of Beethovens Third Symphony, the Eroica, each new generation of concertgoers and music-lovers can probably benefit from being reminded of quite what a ground-breaking work it was when first performed in 1805. At that time its immediate claim to notoriety was that it appeared to have rudely broken the mould of the Viennese Classical symphony at a stroke, and in some ways it had. However, it was not merely a musical form that it changed for good. The Eroica also revealed a new and powerful expressiveness of both a personal and a societal kind. Private importuning with appeals to the emotions was to become the staple of the Romantics with whom Beethoven overlapped. But the more public kind of button-holing achieved by the Eroica and its successors (particularly the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies) seemed to carry an earnest message that was easy to associate with numinousnot to say grandioseconcepts such as Will and Triumph and even the Brotherhood of Man. This was something quite new.

Beethoven himself made explicit the connection between the Eroica and Napoleon Bonaparte, and the symphony does indeed have revolutionary overtones of various kinds. Yet today this seems less important than the effect it has had in the past two centuries on the whole course of Western music. Just as France has its Revolution, so Germany has its Beethoven symphonies: thus Robert Schumann declared in 1839. To Beethovens symphonies we can directly attribute the modern orchestra and its conductor, the modern concert hall and the modern concert programme, of which they are still a core element (one that is much resented in some quarters). How this came about is worth a closer look.

First, though, it might be useful to put Beethovens music and the style he inherited into historical context. No matter how original a musician he was, he still faced the same basic problem that any composer of abstract music faced and still faces: how is he or she to keep it going? This is obviously less difficult for music that is narrative in the sense of setting a text, accompanying a film, or representing in sound scenes such as battles or pastoral landscapes. But in the absence of such external ways of driving music forward it all becomes more problematical. For instance, it is well and good to start with a great tune, but there is a limit to how often it can just be repeated. It has to go somewhere. The question remains: where next, and why there? One solution discovered centuries ago was to take the tune and write variations on it, as Beethoven did in the last movement of the Eroica.

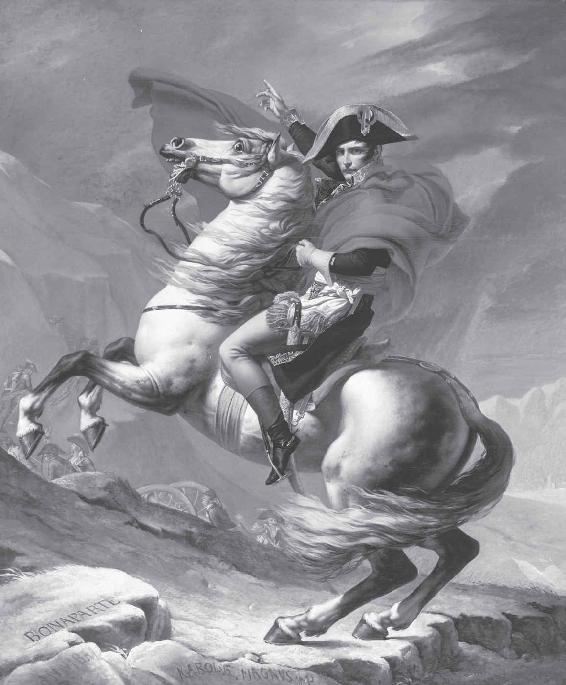

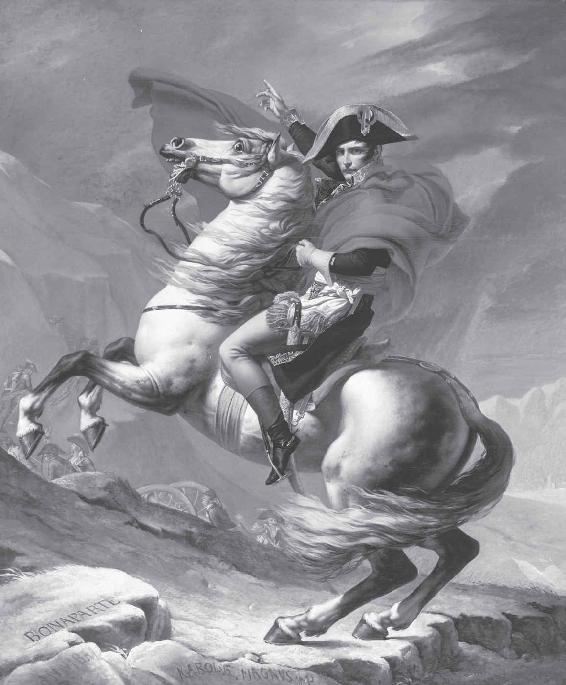

The first Versailles version [1802] of Jacques Louis Davids Napoleon Crossing the Alps depicts a much stylised First Consul leading his troops through the Great St. Bernard Pass in the spring of 1800. In point of fact the weather at the time was unusually clement but Davids invention of a following gale and scudding dark clouds added the necessary touch of Romantic heroism. Compare this with the account of a clap of thunder at the instant of Beethovens death in 1827 as reported by his friend Anselm Httenbrenner.

C REDIT: B EETHOVEN H AUS, B ONN

VARIATION FORM

As the name suggests, this involves taking a tune and decorating or altering it in different ways while still keeping it recognizable. In earlier times sets of keyboard variations (like some of Handels) could be fairly monotonous and conventional. J. S. Bachs Goldberg Variations were probably the first set to show what could be achieved with the form. In the latter half of the eighteenth century and with certain exceptions (for example in a number of symphonic and instrumental works by Haydn and Mozart), sets of variations often tended towards salon triviality. After initially writing variations mainly for his own use to show off his skill as a pianist, Beethoven increasingly used the form to express some of his most personal music. In his later use of variations, the tune he started with often became harder and harder to recognize as he imaginatively exploited its remoter possibilities.

Apart from variations, what else might drive a piece of music onwards? In the Medieval period when most European music was either ecclesiastical or folksong the problem of the form music might take was presumably less pressing because either words or dancing provided the extra-musical impetus. However, composers who wanted more sophistication to their music than was afforded by the beautiful but wandering and somewhat shapeless unison of Gregorian chant were well aware of the problem of form. Above all, they wanted some interesting harmony. With the late fifteenth-century masses and motets of composers such as Ockeghem, Josquin Desprez and others of the Franco-Flemish school an ingenious style evolved, leading to the great works of Palestrina. This was contrapuntal music of astonishing complexity, often taking a popular tune as its foundation and elaborating it by means of intricate canons and inversions and other devices.

COUNTERPOINT, CANON AND FUGUE

Instead of a tune being harmonized vertically, with the four voices (soprano, alto, tenor and bass) forming simple chords beneath it as in God Save the Queen or Kumbaya, counterpoint has the voices running horizontally against (counter) each other. Usually each voice has its own tune, and it is up to the composers skill to make these individual tunes integrate in a harmonically pleasing way. At any one moment, taken vertically, the voices might not harmonize at all; but the ear expects them to come together shortly and resolve any discords, and it can be immensely pleasing when they do, like any other kind of deferred satisfaction. One of the best-known early examples of this is Thomas Talliss magnificent motet