Leonard Bernstein

This book is affectionately dedicated to HELEN COATES with deep appreciation for fifteen selfless years

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Robert Saudek and Mary Ahern for their invaluable critical help in the construction of the Omnibus scripts, and to Henry Simon, the godfather of this book, and Jack Gottlieb, my assistant, for their excellent editorial assistance in preparing this book.

L. B.

Part 1: Imaginary Conversations

Scene I. Why Beethoven?

Scene H. What Do You Mean, Meaning?

Part II: Seven Omnibus Television Transcripts

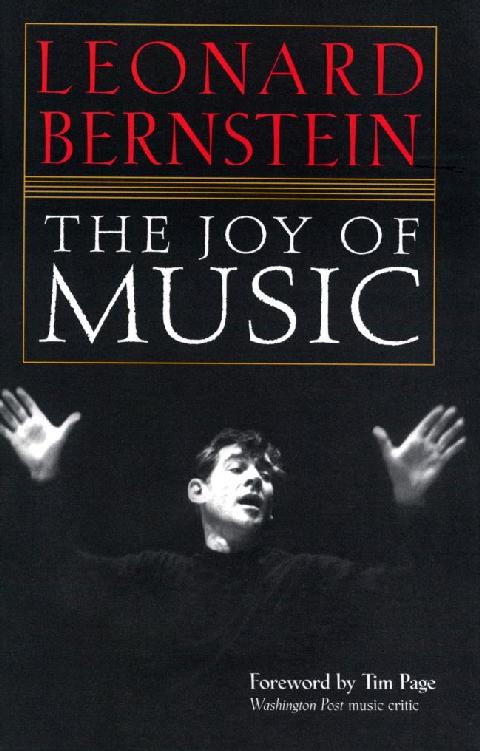

In addition to his many distinctions as composer, pianist, and conductor, Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) found time to be the most influential music teacher in history. That's a big claim, of course, but I stand by it. I met the man only four or five times (and then briefly) but, thanks to his television appearances and books such as The Joy of Music, I can say that I studied with Leonard Bernstein, and so did most of my contemporaries. Indeed, if you grew up in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century and you care enough about music to be reading these words, you are almost certainly one of Bernstein's students, too.

For those of us who were raised in rural surroundings, far from concert halls and subscription series, watching and listening to Bernstein on television in New York Philharmonic: Young People's Concerts was like a passport into another world. With his concise, cogent explanations, balletic movements, and poetic face reflecting, in turn, suffering and ecstacy, Bernstein seemed the personification of music.

The Joy of Music was Bernstein's first book, and (in addition to some funny, incisive imaginary conversations) it contains the scripts for seven early television appearances on a long-ago program called Omnibus, which predated Young People's Concerts by several years. The opening sentence sets the tone: "Ever since I can remember I have talked about music, with friends, colleagues, teachers, students, and just plain, simple citizens." And that's exactly what The Joy of Music is-talking about music, with passion and authority, but always on a level that will reach everybody who cares to listen. The young Bernstein, still in his thirties, was already (as Virgil Thomson once described him) "the ideal explainer of music, both past and present."

Indeed, he seems to have sprung to life fully formed. From the beginning, Bernstein operated in the general vicinity of what might now be described as multiculturalism, with a taste that was wide-ranging and bracingly catholic. He analyzed Beethoven's sketches for the Symphony No. 5, but delved into the syntactic structures of jazz no less deeply. With equal clarity, he explored the radical innovations of Stravinsky and the trusty conventions of the American musical theater. And, in an era when most conductors treated their art as mysterious metaphysical shamanism that defied rational analysis, Bernstein actually took the time to explain just what it was he was doing up there on the podium.

His program on Bach is unusually personal. Bernstein admits that the composer's music meant very little to him until he reached the age of seventeen: "Before that, Bach had meant only some pretty monotonous stuff I sometimes heard at concerts and on the radio, plus some piano pieces I was given to practice." Still, by the end of the lecture, after comparing Bach to Beethoven, Rachmaninoff, Cesar Franck, Tchaikovsky, "oriental folk music," jazz, "Frere Jacques," "Three Blind Mice," and more, while returning again and again to the St. Matthew Passion, Bernstein has made a brilliant popular (indeed, populist) argument for Bach, a composer who was then probably more revered than loved.

Variety succinctly summed up Bernstein's appeal: "[He] has the knack of a teacher and the feel of a poet. The marvel of Bernstein is that, like the writer of television melodrama, he knows how to grab attention and how to carry it along, measuring just the right amount of new information to precede every climax."

Re-reading The Joy of Music is both inspirational and a little sad. One cannot help but reflect on how times have changed. Our major networks would never put on a program like Omnibus or Young People's Concerts today. Moreover, music education in the United States has become something of a scandal. Think of all the great artists who passed through the New York City public schools, and then reflect on the fact that most of those institutions no longer offer any musical instruction at all. Watching DVD reissues of Young People's Concerts today, one senses that Bernstein presumed a greater musical knowledge on the part of his audience of children than most professional critics in the twenty-first century would presume their grown-up readers to have.

All the more reason to be delighted by the return of this long out-of-print book to stores, libraries, and an eager new audience. Leonard Bernstein still has much to teach us-and his company is a gift.

Tim Page

Baltimore, MD

September 17, 2004

There have been more words written about the Eroica symphony than there are notes in it; in fact, I should imagine that the proportion of words to notes, if anyone could get an accurate count, would be flabbergasting. And yet, has anyone ever successfully "explained" the Eroica? Can anyone explain in mere prose the wonder of one note following or coinciding with another so that we feel that it's exactly how those notes had to be? Of course not. No matter what rationalists we may profess to be, we are stopped cold at the border of this mystic area. It is not too much to say mystic or even magic: no art lover can be an agnostic when the chips are down. If you love music, you are a believer, however dialectically you try to wriggle out of it.

The most rational minds in history have always yielded to a slight mystic haze when the subject of music has been broached, recognizing the beautiful and utterly satisfying combination of mathematics and magic that music is. Plato and Socrates knew that the study of music is one of the finest disciplines for the adolescent mind, and insisted on it as a sine qua non of education: and just for those reasons of its combined scientific and "spiritual" qualities. Yet when Plato speaks of music- scientific as he is about almost everything else- he wanders into vague generalizations about harmony, love, rhythm, and those deities who could presumably carry a tune. But he knew that there was nothing like piped music to carry soldiers inspired into battle- and everyone else knows it too. And that certain Greek modes were better than others for love or war or wine festivals or crowning an athlete. Just as the Hindus, with their most mathematically complicated scales, rhythms and "ragas," knew that certain ones had to be for morning hours, or sunset, or Siva festivals, or marching, or windy days. And no amount of mathematics could or can explain that.