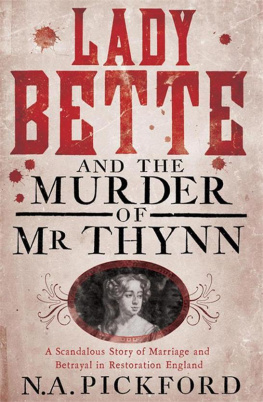

LADY

BETTE

AND THE

MURDER

OF

M R THYNN

N. A. PICKFORD

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

LONDON

For Rosamund

Contents

During the period of this book, the late seventeenth century, the New Year in England did not start officially until 25 March, even though in the popular mind it had already begun on 1 January. In response to the confusion this caused, many wrote the date during the first three months of the year using both numbers such as in the lettering 1681/2 used on Thynns tomb. There was also a ten-day difference between the date in England, following the Julian calendar, and the date on the Continent, following the newer Gregorian calendar.

Many of the characters in this book were happy to spell their own names in several different ways. For the sake of reader clarity I have standardised the many variant spellings. In the case of Bette, her name was pronounced Betty, but I have preferred to follow the Bette style of spelling.

When quoting original source material I have tried as far as possible to use the original spellings, except where clarity of meaning has become hopelessly jeopardised.

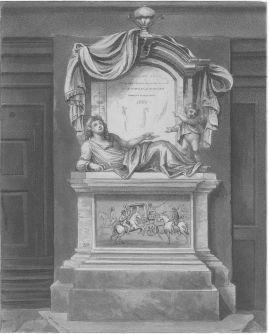

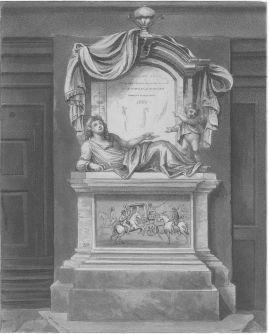

Thomas Thynns Memorial

As through the Abbey wondring strangers pass,

To view the Fabrick, Tombs and painted glasse,

When the Great Thynns Rich monumental shrine

(Which like the Moon, mong lesser Stars doth shine,)

Containing Sacred Relics, Dust Divine;

They see, and by the epitaph certified

How that by murder he untimely dyed:

Desire to know, who was the Cause; the Clarke

With Truth shall soon reply, Count Konigsmark.

Anonymous poem published as a broadsheet 1682

A rnold Quillanworking in such sepulchral gloom. His apprentice Jan Ost stands over him with a lantern, but the flickering light can prove deceptive. One slip now and the work of months would be ruined. He is putting the finishing touches to the tomb of Thomas Thynn. Most of the carving has been completed in the workshop on Ludgate Hill, the Belle Sauvage, but there is always some last-minute pointing and polishing after the slabs have been hoisted and swung into their final positions.

It had been a troublesome commission from the outset. Quillan had spent long weeks on the lettering of a convoluted inscription that had been stipulated by the executors, only for Dean Thomas Sprat of the Abbey to intervene at the last moment and insist on its immediate and total removal. The words may have been in Latin, and so understood only by the few, but they were still an insult to Count Konigsmark, a libel upon Lady Bette, a slur upon the English justice system, and, above all else, they were defamatory of King Charles himself. So the slab had been removed in its entirety and smashed into pieces and a new monument has been lowered solemnly into its place which reads simply:

THOMAS THYNN of LONG LEATE in Com. WILTS Esqr.

Who was barbarously murdered on Sunday the 12th February 1681/2

No fingers pointed. No explanations offered. Below is just a large and empty space.

Quillan gets to his feet, brushes the dust from his shirt and stretches his cramped legs. He is a tall, well-shaped man, not yet thirty years old, an immigrant from Holland. He stands back a couple of paces and views his handiwork. His own name is already being spoken of in the same breath as the great Grinling Gibbons. There are those who are saying he may soon surpass him.

Quillan is well enough pleased with the top section. He has embellished it with the required paraphernalia of swagged curtains, pediments and urns. Thynn is shown reclining with a cupid at his feet. He is gazing heavenwards, his lips slightly parted, a limpid expression on his face, indicative of his saintliness. Neither the executors nor the Dean could surely quarrel with any of that. But it is the scene depicted below upon which Quillan has lavished his greatest care.

It records the moment of Mr Thynns brutal murder. Three horsemen are shown attacking a fashionable coach. One of the assassins, with elaborately coiffeured hair, which falls forward in two lustrous locks, catches hold of the carriage harness. A second, wearing a small three-cornered hat, threatens the two footmen travelling pillion. The central figure of the three shoulders a musquetoon and discharges its fatal contents through the coach window. Thynn throws his hands into the air in a gesture of horror and despair.

The Abbey, as always, is busy with tourists and pilgrims, antiquarians and beggars, the idle and the curious. Once they have finished viewing the main attractions, Elizabeths tomb or the painting of Richard the Lion Heart, the more adventurous wander off towards the South Choir Aisle to gaze upon the newcomer who has just taken up residence there. Everyone of course has their opinion about the murder. Some say the young and handsome foreign Count, Karl Konigsmark, who was quite the talk of the town, commissioned it for love of Lady Bette. Others think it was the fourteen-year-old girl herself who was behind the killing, and if Konigsmark was involved at all, it was only out of gallantry. Then there are those who whisper that Thynns death was nothing to do with love or honour, that there are many in high places who are glad to see him dead, especially the Catholic conspirators.

Quillan professes no opinions. He is not paid to profess opinions. He is paid to raise monuments to the dead, magnificent shrines to embellish the memory and to immortalise the names of the departed.

Soldier and Girl in a Brothel by Frans Van Mieris

Hes well acquainted with the ostlers about Bishopsgate Street and Smithfield, and gains from them intelligence of what booties go out that are worth attempting. He pretends to be a disbanded officer, and reflects very feelingly upon the hard usage we poor gentlemen meet with, who have hazarded our lives and fortunes for the honour of our Prince, the defence of the Country, and the safety of religion... At such sort of cant he is excellent. Ned Ward, London Spy

I n August 1681 Lieutenant John Stern, forty-two years old, a soldier by trade, washed up in London. Like Quillan, he was an immigrant, one of the thousands constantly deposited by the tide on the muddy shores of the Thames. Unlike Quillan he didnt have a job or a network of contacts. He arrived wearing a small three-cornered hat and among his meagre possessions he carried a single book, Dilherens Way to Eternal Happiness , a self-help guide to getting into heaven. He had been kicking around northern Europe for the previous twenty-three years, enlisting in whichever army would have him. His only marketable skill was killing people.

In his Last Confession , hastily scribbled in Newgate Gaol, Stern claimed to have been born of Swedish nobility, a son by the left hand as he put it. It may have been true but his failure to name his father does not inspire confidence. There is not much about Stern to inspire confidence. There must have been some family money, because after he left his native Sweden at the age of fifteen he spent two years at school in Germany. This smattering of education, however, just made his present reduced circumstances that much more galling. He clearly saw himself as a cut above the general run of illiterate cannon fodder.

Next page