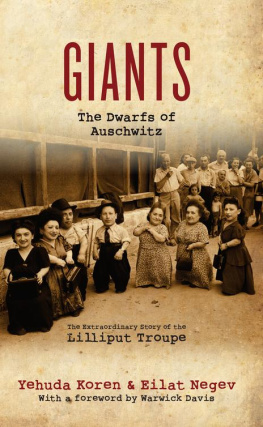

S everal years ago, I was researching the subject of short people in entertainment for a potential film or documentary idea. My doing this was also borne out of a personal curiosity about such performers, and why they did what they did. Among tales of medieval court jesters, Tom Thumb and the dwarf town in Coney Island, I found the inspirational story of the Ovitz family. My research was not thorough or in-depth at that point, but what I did discover about the family left a lasting impression.

In the spring of 2012, I was approached by a television producer who wanted me to tell the story of the Ovitz family for a documentary. This was one of those offers that needed no consideration and I agreed to it immediately. I remembered what Id read about the family of seven dwarfs all those years ago and how amazing I thought their story was.

Before production started, I wanted to research more thoroughly the family, their lives and their ordeal at the hands of Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, but I was stopped. The director of the documentary wanted this to be a journey of discovery for me, as well as for the viewer, so I closed the textbooks and opened my mind.

In October 2012, I set off to Romania and to the village of Rozavlea, where the Ovitz family were from. I spoke to people who knew them and visited the house where they all lived together.

One of the most pleasing things I discovered about the Lilliput Troupe, as they were known, was that they were professional performers through and through. These were not seven dwarfs who went up onstage as some sort of novelty act these were proper entertainers who just happened to be short. This really resonated with me. I started my acting career at the age of eleven, getting a part in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi because I was three feet six inches tall. It wasnt because I was a great actor; it was simply because I was the right height for the job. However, even at that early age, I realised that to sustain this as a career I would have to focus on my performance and that being short should not be my selling point.

Not only are the Ovitzes inspiring as performers, but as people too. They survived Auschwitz, the notorious Nazi death camp, by sticking together, supporting each other and never giving up hope.

On a cold, bleak day in late November 2012, I went to Auschwitz II (Birkenau) to film the final sequence for the documentary. Actually being there had a really profound effect on me. I was able to stand where the Ovitzes stood, see the things they saw, in particular the view of the chimneys from the crematorium that Perla Ovitz had described seeing after disembarking from the train onto the ramp. I also went to the accommodation block where the Ovitzes had spent much of their time in Auschwitz. I took two handmade tiaras that belonged to Perla and Elizabeth, part of their stage costume that had been loaned to me by the authors of this book. I laid the tiaras there for a few minutes as a mark of respect for the family, and a symbol of their triumphant survival. It was a very poignant moment.

My only wish is that I could have met Micki, Elizabeth, Perla, Rozika, Franziska, Avram and Frieda. I would like to have been able to get to know them, relate to them and find out where they found the strength and courage to survive their time in Auschwitz. However, Yehuda Koren and Eilat Negev have allowed me the next best thing by writing this book.

It manages to convey all the vibrancy, passion and hope that these seven wonderful souls gave to the world. They should never be forgotten.

It leaves me both inspired and humbled. Thank you.

Warwick Davis

December 2012

T heres a long pause after the chime echoes inside. No ray of light sneaks from under the door. No movement. No muffled noises disturb the quiet afternoon.

Two peepholes, one above the other, catch the eye. The lower is just thirty inches above the ground. Until not long ago, Perla Ovitz would drag herself and peek out, trying to guess by the look of the trousers or dress hem if it was a friend or foe. Nowadays, confined to her bedroom, shes too weak to make the journey. Her vigorous voice erupts from a loudspeaker in the hallway; it demands identification. Only then is there a buzz, and you can push the heavy brown door open. You blink in the dusky corridor. You are not sure how to continue, for fear of slipping or bumping into concealed furniture, or worse, trampling over the hostess. Shes less than three feet tall, and you might squash her unintentionally.

Her voice is your compass, guiding you forward. You grope blindly towards a diminutive silhouette that clings to the doorway of the dimly lit room. She waits at the threshold in a full-length majestic crimson dress, and allows her visitor to tiptoe past. You step carefully inside. Only then, she waddles in.

It is her bedroom. The legs of the double bed have been sawn off and, although it is almost lying on the floor, a small stool stands next to it, to enable her climb into sleep. Beyond a kindergarten table and chairs is a child-high washbasin. From your towering angle, theres not much difference in her height if shes standing up or sitting on the edge of the bed. Your first impulse is to shrink down, so as not to dwarf her with your presence. She nods towards the normal-sized sofa beside her bed. You take care to keep your feet on the ground, as crossing your legs will push your shoes straight into her face.

The raven-black hair of the ageless doll-like lady is carefully combed back, and held in place by a velvet bow, in old-fashioned Hollywood style. Shes theatrically made up at all hours, her cheeks are rouged, her nails are lacquered shiny red. A pair of earrings, a necklace and rings ornament her. As long as you breathe, you should look your best. I dont want people to pity me is a recurrent motto of hers.

She enchants with her dazzling smile and her bubbly talk is studded with unexpected aphorisms: a beaten dog dreads even the kindest people is how she excuses her cautiousness. She spends most of her time sitting on her petite chair or reclining, dressed, on her covered bed, as these days she can stand no more than a minute or two unaided.

Shes on her own most of the day, and needs everything to be easily accessible a packet of chocolate cookies and a plastic box of sliced apples lie on the bed should she get hungry. A thermos with water waits within reach.

She cant move without her cane, which serves as an extended hand, to pull, press, push. Tiny stools scattered through the house allow her a brief rest in her movements around the flat. All the light switches have been lowered to her height. The kitchen has a knee-high stove and a special mechanism allows her to open the refrigerator door with a push of her cane. All the food is stored on the bottom shelf.

Vases that stand tall as her hold abundant bouquets of silk and plastic flowers, in her favourite colours: sharp violets, soft pinks. A heavy red curtain at the wide entrance to the living room is pulled to both sides and gathered in thick cords, as if a show were about to begin. Forty-five years have passed since Perla Ovitz took her last bow, but the stage stays with her still. Once, when all her family was still around, she loved the lights: she even flooded herself with them off stage, at home. Now, trapped alone in this big empty apartment, she seeks the economy and safety of dimmed lamps and half shadows.